January 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

- Accept gift of prepackaged, pre-cooked rice. It should be mixed long grain, wild, and red, for best results.

- Add the last of your salted peanuts on top. Be sure to tap out all the salty crumbs.

- Microwave until hot.

- During this one minute of cooking, peel your orange.

- Take out hot plate using your towel, as there will be no hotpads.

- Pull apart your orange slices and arrange them around the edge of the plate in a pleasing pinwheel design. Presentation is everything. Perfecto!

- Eat alternating between sweet and salty. Touch your finger into the last crumbs of peanut bits and eat every single one.

- Choices for dessert: corn nuts or a ginger candy. I say go crazy, have both. Careful of your teeth, though.

January 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

nomads and wanderers, wherever you are

sleep well, you pilgrims and vagabonds, under the stars…

— from the chorus of “Nomads and Wanderers”

Yesterday’s albergue was new and modern and so clean. Today’s albergue was old, dirty, and rundown, so I planned to sleep in long sleeves and long tights, to avoid any bug bites, just in case. How quickly my situation changed, day to day.

Here, I was straddling the old and the new. The Camino now followed an old Roman road, passing a Roman mile marker near the bar where I drank coffee. I would cross a Roman bridge tomorrow. I had chosen the Primitivo for these very days, to walk in the millions and millions of footsteps of all those who had walked this Way before me, from after the life of Christ into Viking times, through the Middle Ages into this modern day.

My Middle Age: a milestone. Retracing my steps down the road to study that mile marker, I stood facing the Romans’ assertion of their dominion, carved in granite. And look at them now. All roads actually led to a different Rome than they might have been considering when they erected this supposedly permanent way sign. The message was hidden in plain sight: back to the zero-mile, the beginning and the end, center of a penciled compass arc of influence and power, easily erased and redrawn by Time.

As I passed these oldest landmarks, I found myself noticing the oldest people along the Camino. Elders were grabbing my heart and my attention in these last days of the Primitivo, before my path joined the Camino Frances into Santiago.

Yesterday, at the cathedral in Lugo, an old woman dressed in black paced slowly before the doors, keening in mourning for her husband. Not a loud wail, she moaned her pain and panic, tentatively extending her begging cup. My immediate streetwise thought was, Nice strategy if you’re homeless – well done. But as I approached her and tried to talk to her, it was apparent that at some point, she had actually lost her husband; she was obviously elderly; and homeless was homeless, so survival was now the full-time strategy. I might have used my grief to let me live, too.

When my father died, I was devastated. He had been the sanity of our family, the grounded stabilizer, fortunately or unfortunately attracted to the wild energy of my mother’s neurotic demands and rages, deeming this passion. His personality was friendly, down-to-earth, and also expansive; he offered that wide, generous pasture, because he needed it himself. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

He, too, roamed in his day, and told stories about taking a train west when he was only 16, dreaming of becoming a cowboy. When he reached the ranch that had hired him, that’s exactly what he found, cows and more cows. But to his utter dismay, these were not longhorn dogies for a dusty cattle drive to Abilene – no, they were milk cows. He’d come 700 miles to the dry eastern plains of Colorado, not the stunning mountains, to milk cows, just like back home on the farm.

Yippee-ki-yay.

But that didn’t stop him. He soon enlisted in the Marine Corps, and was sent to the Pacific at the end of World War II. The horrors of battle never realized, he spent his tour cleaning up after battles already gone by, clearing beaches, patrolling beaches, swimming beaches. After learning to smoke and drink, he came home with a new and shocking vocabulary, a gorgeous tan, and a beautiful hula girl tattoo on his bicep that he could make dance by flexing his muscles.

What I remember most about his stories of those days was the way his eyes changed when he talked about the ocean. His hazel eyes reflected a certain light he had seen, over a wilderness of endless water, unfathomable, expansive beyond description. The ocean had given him something profoundly personal, spiritual, and I always wanted to follow that light, to see what he had seen.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Today, I came upon a wonderful elderly woman slowly making her way up an old mossy-walled stretch of the Camino passing through woods. Again, all dressed in black, again, not understanding when I tried to explain I could not understand Spanish well. But when I took her hand, the skin papery-thin, she got teary, so I leaned in close and said, “Buen dia, señora, buen dia,” as I kissed one cheek, then the other. She smiled and touched her teary eyes, saying words that sounded like, “Buen viaje,” though I wasn’t sure. Still, I took that meaning, and walked on. It was so hard to leave her; I felt like I wanted to make sure she made it home all right. But this was her life, and she’d let me go, so I let her go and kept walking.

Mostly this day I remembered things from childhood, as if I had become an old abuela, too, slowly using my stick to walk the path, my head draped in a scarf against the sun, telling stories of days gone by to my grandchildren, all of which I was most certainly doing, even writing tales into my notebook in the evenings. Feeling tears rise at the kind gestures of strangers, and at my inability to do more for others in return. Indeed, I was walking her mossy path.

I remembered my favorite picture book from when I was five, where the little boy, Lester, traveled the world making friends, riding an elephant, flying on a dragon kite, seeing storks in their rooftop nests, floating on a red balloon past the Eiffel Tower. How I had longed to go with him. And also the Dr. Seuss book, “McElligott’s Pool,” where anything exotic from any far away place was possible to find, if you remained “patient and cool.” Oh, and how I wanted “Scuffy the Tugboat” to sail out into the sea at last, and not return home to sail in the bath tub.

I remembered working in our fields, walking beans and baling hay with my uncles and my grandpa, saving my pay at $1/hour to finally buy an army surplus rucksack of olive green canvas that I used for going everywhere, until I wore it out.

I saw now that this had been a lifetime obsession for me, not since 17. Lifetime. Always, this had been me: ready to go, searching for adventure.

The dirt of the Camino crunched under my feet, as I wiped sweat from my face. I remembered my grandma kept small potted cactus on the kitchen windowsill over the deep chest freezer filled with homemade cinnamon rolls and hearty breads and sweet corn sliced from the cob and thick cuts of meat wrapped in white butcher paper. The wonder, to me, was not the abundance of food (we lived on a farm); it was the foreignness of desert life in the midst of the Midwest. So fascinating to me, that if we gave the cactus water, it could be too much and kill them. How do they live?, I had wondered. What would the desert be like?

Now I knew, and cactus still amazed me. Understanding the world a bit more in no way diminished its magic; if anything, it let me bring it with me, visualizing the desert, or my grandparents’ farm, or the snowy Rocky Mountains, using the learning of direct experience to make the magic last. It was the learning that seemed to stick with me best, and the kind I had pursued least, until now. How long I had waited. Hardly patient and cool, though.

My father and I had come by this wanderlust naturally. My grandpa, Holger, was first-generation American. His parents had crossed the Atlantic from Denmark, searching for something more. The heartbreaking story of his father, Christian, was all too common: having bought a farm, he settled into his life in America, he married, and they had a child, a little boy; and, when diptheria claimed the wife and five-year-old child, Christian was devastated. A handsome, dashing, blue-eyed Dane with a gift for jokes and storytelling, he became somber and defeated, his loss too much to bear. When he finally remarried, it was to a sturdy, quiet, dependable woman who bore him several more children – the first of whom was Holger.

Holger was a chip off the old block. His eyes twinkled merrily whenever there was a party to be found. He loved to talk to people, and people loved to talk with him, and he had many friends. But Christian never appreciated this trait, his own fun-loving charisma reflected back to him, and he and Holger struggled to get along. Holger, in turn, tried to knuckle down and be responsible. He went to college using the ROTC program, an Army second-lieutenant at the end of his term who was unable to obtain the final credit needed for his horticulture degree, because he could not pass the college English exams. The family spoke only Danish at home.

Undeterred by this setback, Holger bought land from his father and started farming. He married a sturdy, quiet, dependable woman who bore him several children – and this is when the problem began.

Holger was like the original Christian – the life of the party. He had married a girl just like the one that married dear old Dad, even though Holger had not gone through the devastating loss and grief of his father, had not lost his sparkling belle of the ball. Even Holger naming his own first son after that first son Christian had lost, had made no difference in their relationship. Now here he was, living something very akin to his father’s life of mourning, an adventurous young man of joy and passion. The family always said they could never understand why he did what he did next – but I could.

Holger took off. He headed west, of course, into the fabled promised lands of America, where a person could find wide open spaces and opportunities to reinvent himself. Oh, give me land, lots of land, under starry skies above – don’t fence me in. He went all the way, as far west as he possibly could drive, to the coast of California. There’s a picture of him, sitting on a dock, facing the ocean, his jaunty cap framing a beaming smile.

That picture had captivated me as a child. I had never seen my grandpa so happy. My aunts made disparaging remarks when I asked about it, and my uncles laughed and used it as a punchline to their jokes. But my father – he didn’t say anything about it.

Grandpa Holger was back about two weeks later. In my heart, I’m confident he had gone to make a decision. Overwhelmed with the responsibility of the farm, hired hands, several small children, his wife, all struggling together as they trudged through the Great Depression, he’d run, to clear his head, to choose between the life he had fallen into and the life he had never let himself find. That photo showed me Holger right before the heartbreak of his life: giving it all up, that wide-open freedom, and returning.

Holger was a good man. He became a respected pillar of the small community. He helped a lot of young couples get started farming, selling them sections of his own land for much less than it was worth. He took Grandma to church every Sunday, took his turn ringing the bell. He could be counted on to help his neighbors whenever they needed him.

He loved a good joke forever, and a good rascal – like me. Always disapproved of for my latest shenanigans, always the recipient of my aunts’ bossy admonitions, he always laughed whenever

I got myself into trouble. As I walked into that farmhouse kitchen and found him standing there, he’d reach out his brown, gnarled hand and tossle my already tossled hair, saying in his gruff, thickly-accented English, “This one – this one I like.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

At one crossroads, an older man with silvery hair sat on the wall with his two dogs at his feet. As I approached, suddenly, he jumped up with a shout, and he and the dogs ran down the righthand road. When I got to the intersection, an older woman in a long dress, apron, and headscarf stepped from the small barn before me. We could see then that four sheep were out of their pasture and strolling up the small road. The man was having a time herding them in again with some help from the big dog, while the small dog rolled enthusiastically in what looked like dried manure on the road. The woman and I chuckled together. I understood that these were older, newly-weaned lambs, because I could just make out she said that they didn’t want to get their own food, they just wanted milk. They had gone in search of their mothers.

So had I. After years of escaping fences and running down the wrong roads, I had finally sat down and reread the story I told myself, slowly, carefully. My mother’s story had shown me how poison seeps down through the generations, a hidden leak of deadly contamination oozing toxic trails through our lives. Long ago, I had processed what happened, but hadn’t taken time to look deeper into how, and why, everything happened as it did. High on the mountain, I had stumbled onto understanding, perspective clear and fresh as this woman’s smiling explanation of the lambs.

But in an unexpected twist of fate, like all the best tales, searching for her story had led me into my father’s story, and his father’s. Rereading this story, I saw how good people can break their own hearts, by trying to be what they think they should be, instead of being who they are; by mistaking passion for irresponsibility, or rage, or just some children’s fairy tales, instead of recognizing it as the divine spark of the soul. Another cautionary tale.

I remembered my grandpa, many times, out on the tractor alone, the summer sun slowly sinking late in the evening. He was out haying, steering into rippling waves of an endless, golden, shining sea of grass.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I met an old woman who looked like me. As I sat on the bench of a roadside fountain, she walked up silently in her worn shoes and the long apron she had patched, and handed me a ripe pear.

I looked up at her and saw my aged face looking back at me. She said she couldn’t eat it, opening her mouth to touch her sore tooth. Then she took out her whole lower denture, my most unexpected surprise of the day, but not entirely strange for me: it reminded me of when my homeless clients always wanted to show me their blistered feet. “I believe you, I believe you,”

I would say in protest, holding out my hand, attempting to ward off the inevitable.

She showed me that the tooth was loose, the gum inflamed. I told her she needed a médico, and

I was not a médico. She motioned that they needed to just pull it. I pantomimed: they yank it, “OWWW,” then relieved expression, “AAHHH,” and she cracked up laughing, nodding and agreeing with me. Then she wished me buen camino and, chuckling, walked back down the lane.

The pear was perfect – soft, juicy, delicious. My tongue instinctively checked my broken molar, the root canal that had never gotten its crown. Still, I savored the sweet taste, juice dripping off my lip and through my fingers, imagining one day soon, I might not be able to.

Or, they needed to just pull it.

“Getting old is not for sissies,” my dad had told me. How quickly time passed, day by day, straddling the narrowing gap between youth and old age. I planned to savor every delicious moment, hand in hand, side by side, with as many people as I could possibly meet, blistered feet notwithstanding. Teeth or no teeth. A little thing like that wouldn’t stop me – I had places to go, people to see.

some people stay

and some walk away

some stand, one foot in, one out

and dance in the doorway

some hear a call

like a great waterfall

it plunges them up over under

and carries them forward

nomads and wanderers, wherever you are

sleep well, you pilgrims and vagabonds, under the stars

vikings out hiking beyond, over hill or by sea

like my grandfather, my father, and me

wandering along

with your heart full of song

you carry your life on your back

and that’s where it belongs

the people I love

are the people I meet

if you meet me halfway I will stay

for a coffee or two

nomads and wanderers, wherever you are

sleep well, you pilgrims and vagabonds, under the stars

vikings out hiking beyond, over hill or by sea

like my grandfather, my father, and me

— “Nomads and Wanderers”

January 8, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Indulgence: remission of part or all of the temporal and especially purgatorial punishment that according to Roman Catholicism is due for sins whose eternal punishment has been remitted and whose guilt has been pardoned (as through the sacrament of reconciliation).

— Merriam-Webster

As I strolled toward Lugo with a young Frenchman named Fred, we passed through a tiny village, or maybe a large farm; it was hard to say. A huge tree stopped us in amazement, so old and so much a part of the place that the usual stone wall was built right into its massive trunk, the gate attached to its other side.

As we stood marveling and discussing the age of such a tree, a sweet dog and a puppy came out to greet us. The dog took a soft head rub from each of us and, tail wagging, trotted back to the nearby house; but the puppy had recently gotten its new, sharp teeth, and kept playfully attacking our ankles. Fred laughed in fond delight, until the naughty puppy quickly nipped a hole in his sock, so that Fred shouted in surprise and shooed it away with his hand as he assessed the damage. The pudgy little ball of energy then pounced on my foot, untying my boot lace. We dissolved into hilarious tears of astonished laughter as we tried to walk, first one of us with a puppy on our boot, then the other, runny the furry gauntlet of one determined little canine toddler, until the puppy finally got tired and we made our laughing escape.

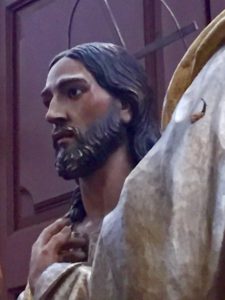

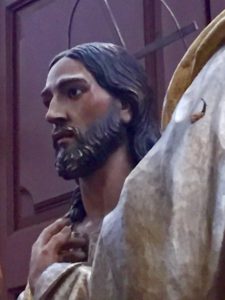

The Beloved Disciple resting his head on Jesus’ shoulder

At the beginning of the Camino, I had read in my guidebook about loose dogs, especially on the Primitivo, and strategies to defend yourself from them. I had planned to buy dog treats, but at each market, if they had any at all, they came in bags much too big and too heavy to be of any practical benefit for a pilgrim. A ploy was just a burden, it seemed.

Nevertheless, I had now survived my run-in with wild Primitivo dogs, armed only with indulgence. The Latin origin of “indulgence” meant to be kind, tender, an aspect of coddling, and babying, which all led back to mothering.

When Fred joined me in my slow walking, I couldn’t help but notice I seemed to collect quite a few young adults along the Way. Fred, Felix, Francesca, and also Jana, eighteen and brand new to adulthood, and the two young Japanese girls who had no English or Spanish, but waved and smiled whenever they saw me, sometimes gesturing at crossroads, their faces asking the question until I pointed them in the right direction, showing them an arrow farther ahead and receiving their reassured expressions and deep nods as bows of appreciation in return.

Life-size tableau of “The Last Supper” within the cathedral of Lugo

All the ages of my own children, I enjoyed our talks about the meaning of the Camino, why they had come, and what significant life choices awaited them when they returned home. I found myself by turns encouraging and reassuring them, Fred deciding about buying his first house or traveling, Francesca leaving her “good job” for taking an ethical stand, Jana waiting for other young Camino friends who never came, and Felix – I just hugged Felix as often as I could get away with it.

They reminded me that I had moved on, beyond my teens and 20’s and 30’s, and they looked to me for some sort of wisdom I was not at all sure I had. Santa Barbara was no saint. The only thing I had to give them was experience, the gritty real-world learning of having been in hard places making hard choices, and living to tell the tale.

They reminded me that I had moved on, beyond my teens and 20’s and 30’s, and they looked to me for some sort of wisdom I was not at all sure I had. Santa Barbara was no saint. The only thing I had to give them was experience, the gritty real-world learning of having been in hard places making hard choices, and living to tell the tale.

So I told stories. As each fit into the stream of conversation, I talked about being newly divorced with preschool-age children and how perseverance had generated its own luck in finding a job, work which eventually became a career. About the humiliations of poverty, receiving food stamps that store clerks shamed me for using, just to buy a 79¢ mix to make a birthday cake for my three-year-old. About “This Damn House,” as I had christened the money-pit

I finally bought, a flat-roofed, wood-floored beauty in her day, leaking water and cold air and home improvement projects into all my weekends, but big enough and sturdy enough for raising

a family.

As I told my stories, images of my children rose up before my eyes, and I could hear their tiny voices and high-pitched laughter, their arguments and tears, and see them expectantly giving me gifts of smudgy kindergarten hand print art, receiving school awards, graduating high school, graduating college, telling me about jobs and friends and love relationships and having their first babies, buying that first house.

I knew I had lived all those experiences, and yet, I didn’t feel older and wiser. And yet I was. How strange, to become an elder without realizing it. I wasn’t convinced I had earned that position.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Brought up Lutheran, I knew Martin Luther had fought corruption he saw in the medieval Catholic Church, including the sale of “indulgences,” essentially “Get Out Of Purgatory Free” cards sold by church authorities, sometimes obtained by significant acts of penance – such as walking a pilgrimage. Since starting the Camino, I had learned that this substitution had gotten to the point where some people in the Middle Ages hired pilgrimage-by-proxy, rich sinners sending poor serfs out to risk their lives on dangerous trails to holy sites, obtaining a compostela in the name of the wealthy scoundrel.

I had discovered a deep satisfaction in walking my own Camino, finding my own way, carrying my own burden. I was also discovering my own delights, and taking them, intentionally and without apology. Not very Lutheran. I knew I was being changed by the Camino, and would not be returning to my previous life, my 8-to-5 office, my weekends at plumbing supply stores. I was dancing over obstacles, surfing this powerful experience under a glorious sun. The rebel angel inside was singing, some sort of loud, punk rock anthem, the only words I could hear:

remember all the desperation of our love

the teary kiss, the frantic hug

the joy we crucified, a passion play

and on that cross we built ourselves we hung our love

and like a phoenix from a dove

we burned the tree that held our heart’s desire

smoke and cloud

days of pyres

running on fire

remember looking for the key for every door

and finding none, imagined more

the possibility of heresy

remember when we realized the world was round

and more than this could well be found

and how we raised a sail to save the day

smoke and cloud

hazy tower

prison on fire

— “The Reformation”

Indulgences required a “Pardoner.” I had finally figured out that this pardoner was me. And the sinner, too, was me. I was the whole shootin’ match. The way out of the fiery gunfight was to quit fighting – quit fighting my history and myself.

I had come on Camino to atone, to make peace with 17-year-old me, the lonely, brilliant, sensitive girl I’d tried to kill off over all those years, for her belief in us. In me. Here she was, defiantly singing the Reformation at the top of her lungs.

Leaving the tower behind was the road to reconciliation.

All I needed was the key. I needed to commit heresy.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, “indulgence came to mean the remission of a tax or debt. In Roman law and in … the Old Testament (Isaiah 61:1) it was used to express release from captivity or punishment.”

— New Advent

It was easy to know when I had reached the Old City of Lugo – I faced a massive Roman wall. Over twenty and sometimes thirty feet high, 14 feet thick occasionally bulking to over 20 feet across, it stretched a gargantuan two-kilometer ring around the central core of Lugo; over a mile of protective stone. UNESCO described this World Heritage Site: “The defences of Lugo are the most complete and best preserved example of Roman military architecture in the Western Roman Empire.” The wall was built in the 3rd and 4th centuries. It boggled my mind: I was standing in the far western reaches of the Roman Empire.

I entered by the Prisoner’s Gate. For hours, I toured the Roman ruins within the wall. Mosaic tiled baths under the street were covered in glass. The same for a section of aquaduct. Temples to Roman gods stood below ground level, next to Christian churches above.

One such temple was Casa do Mitreo, or, House of Mithras. Mithras was a god popular with Roman military men during the time the Walls of Lugo were built, a blended persona based loosely on an even older Mithra from Persia. This Zoroastrian divine angel of oaths, covenants and contracts was hailed as “Mithra of Wide Pastures, of the Thousand Ears, and of the Myriad Eyes.” To the Romans, Mithras’ “wide pastures” referred to his watchful eye over cattle, the currency of many contracts.

As I wandered the Old City, I remembered a gift of wisdom Emma’s father had given me about my sons, especially sweet, creative Daniel, my own Ferdinand the Bull who, as a child, had preferred sitting and smelling clovers on the soccer field to fighting for the ball. He had told me not to rein Daniel in, but to give him a wider pasture, room to roam. I, too, had needed this wider pasture, always. What Emma’s father could give me was the idea, the story, though not the freedom itself. That I had to take, like a stolen key.

This was how I perceived Mithras. Often considered the pagan model for the stories of Jesus, he was the originating idea, the spark. Many scholars drew parallels between the Romans’ December 25th Feast Day of the Unconquerable Sun and the birthday of Mithras, as he was considered an embodiment of the ever-returning sun, and would have been celebrated on that date. His promise to protect was sealed with the blood of the bull, like children pricking their fingers to solemnly swear, becoming blood brothers, becoming Jesus’ story of giving his life-blood for all of humanity.

Yet Mithras was also depicted riding a bull. The bull didn’t die; it lived. It carried Mithras where he needed to go. Onward. Far afield.

This partnership formed the original contract. One of my dearest friends from those long-ago kindergarten days of our children, my beautiful hippy-artist pal, had wisely surmised, “You came to this life, not to be with any of these men – your contract was with the children.”

She was so right. We’d sealed that contract in blood. Paid in full.

He has sent me to heal the brokenhearted,

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and the opening of the prison to those who are bound….

— Isaiah 61:1

I climbed a staircase of stone, and stood on the Roman Walls of Lugo, looking out over the city, back across time. As I looked over the edge, I remembered my own poem about the water man, back along the northern coast: the wall is open, peregrina. It was true. The gates of the massive walls here all stood open, like triumphal arches.

As I slowly walked the path along the top, I thought of what I’d hoped to give my children by this seemingly reckless, irresponsible choice to come to Spain and walk the Camino: that spark. The idea that if they tried to live a larger life in the world, they wouldn’t die. They would find a wider pasture waiting. They could take the steps, see over the top of their own confining ideas of themselves, break down their own limiting walls. Walls for protection can become prisons over time; this truth, I knew.

Virgen de la Esperanza (Hope)

And then I heard something sweet, carried by the wind to me as I stood high on the wall, a child’s voice below: “Mom-my….” In it, I heard Meghan, and then Daniel, and Zach, Emma and Magnus.

They had needed me, and I had answered. Or maybe it was the other way around. We had become partners, giving each other hope, and after the Thousand Ears of a listening mother, a mommy’s Myriad Eyes watching over them, they had given me what I had not been able to give myself, what I had not allowed: forgiveness for my failings, and freedom.

Indulgence. They told me, “Go.” They told me, “This is your life – fly away and live it.” They told me, “Spend all the money. If you run out of money, we’ll send you more.” And best of all, offering me that glimmer of hope I was watching for, they told me, “You know what? I have to say, I’m a little jealous.”

Mithras the Bullrider, may I stoke the fires of that spirit until it burns like the sun, until they recklessly, irresponsibly, and self-indulgently refuse to live captive or unreconciled to themselves in any way, and though they find a wall on one side of the Great Tree, may they find a gate just waiting on the other, opening for the ride of their lives.

January 7, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Gorma was washing out her smelly socks when she heard a strange sound. She twisted them tightly, using her strong hands to wring all the water out, then clipped each sock to the clothesline behind the albergue. As she put her other dirty clothes into the soapy water, she heard the strange sound again, like the trumpeting of a horn announcing a king’s arrival.

Gorma peeked around the side of the building, looking just past the hydrangea and rose bushes near the walkway to the front door. There she saw an animal unlike any in the Land of the Heart: big, round, gray, wrinkled, four great legs and two humongous ears and two long tusks, plus a long, strong trumpet of a nose announcing the arrival of – an elephant.

“Why in the world must I wait?” the elephant was complaining to no one in particular. “On Myland Island, where I come from, we never have to wait for anything. I get what I want immediately. This person should give me what I want. I’m tired, and want a bed, and I want it now.”

Gorma frowned and went back to washing her laundry. It had gotten dusty and dirty from all her walking, but the soapy water felt warm and soft, and as she rubbed her clothes together gently, the dirt was washed away, leaving them clean and smelling sweet. She had just finished squeezing all the water out and hanging them all on the clothesline, when the elephant’s trumpeting sounded in the albergue kitchen.

“There’s no dinner ready for me? On Myland Island, where I come from, we never have to make our own dinner. Someone else always does all the cooking, so that I can eat as soon as I am hungry. This albergue should give me what I want. I’m hungry, and want to eat, and I want to eat now.”

Gorma turned away from the kitchen and instead, went to read her good book in the comfortable chairs in the front room. She smiled at the other travelers seated there, and they smiled at her, and all was quiet and pleasant, except for a lot of banging in the kitchen, which they all ignored.

Again Gorma heard the elephant’s trumpeting sound, this time outside by the clothesline. “Wash my clothes by hand?” the elephant repeated, sounding very surprised. “On Myland Island, where I come from, we use washing machines, and dry our clothes in the dryer. Why, I hardly have to touch my clothes that way, especially the smelly socks, and … and other smelly things. A clothesline? I never use a clothesline. On Myland Island, no one has to use a clothesline.” But soon, the elephant was heard splashing and crashing in the washing sink, and he hung his heavy drippy clothes on the clothesline.

Gorma had gone to make a cup of tea in the kitchen, and after her tea and her good book, she said goodnight to the other travelers, washed her face and brushed her teeth, and slept deeply in the bed she had been given in the albergue for that night, for which she was very grateful.

In the morning, after coffee and toast with peach jam, Gorma packed up her bag with her fresh, clean clothes, put on her cloak for the morning chill, and taking Saint Thomas, her walking stick, she began her day’s journey down back roads and byways. It was a sunny morning, and as birds greeted her and the butterflies led her down safe paths, Gorma felt warm enough to stop to take off her cloak. As she took a drink of water from her water jug, she heard a strange sound, like the honking of a goose who has lost his flock.

As Gorma emerged from the wooded path, she saw a fence with a big gate for cows and sheep, and a small stile beside it, that gap the farmer uses to slip around the gate in a V around the gate post, too tight and too tricky for a cow or a sheep to pass through. “Apparently, too tricky for an elephant to pass through, as well,” said Gorma to no one in particular, for there, stuck in the stile beside the gate, was the elephant. He looked a bit panicked.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, thank goodness you are here. This farmer has built his gate all wrong, and now I’m stuck. On Myland Island — ”

And at that moment, Gorma opened the large gate with a simple click of the latch. It swung wide and welcoming.

“You mean, this gate?” she asked, stepping through it easily, then back again, before pushing it closed until latched once more. The elephant did not know what to say, sputtering now, not trumpeting. His name was Ben, and, as you may have heard, he was from Myland Island.

“You are correct about the stile, however,” Gorma nodded, and Ben the Elephant began to smile, with his complaining face all ready. “You are certainly stuck.” Ben the Elephant looked shocked; then his face crumpled in defeat.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma – can you – how will I? – can you help me…get unstuck?” And at that moment, the elephant looked more like a sheep than an elephant, a little bashful and more than a little embarrassed.

“Of course,” Gorma smiled, and with a lot of encouragement and the strength of Saint Thomas, Ben the Elephant was finally free of the stile beside the gate.

“Wow – gosh – thanks – that was – on Myland Island — ” he began, but Gorma simply said,

“You’re welcome,” and walked on.

Gorma stopped to eat her lunch on a smooth, flat rock near a shady tree. She had just finished her bread and cheese, when she heard a strange sound, like the squeaking of a mouse who is searching for, coincidentally, bread and cheese. Gorma looked back down the trail, and here came Ben the Elephant, slowly lumbering UP the trail.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, thank goodness you are here. The woman at the albergue sent me out this morning with no food, and now it is midday, and I have nothing to eat! Women.

On Myland Island –”

And at that moment, Gorma pulled more bread and cheese from her bag. “You mean, like this bread and cheese I bought from her, at her shop next door to the albergue? Did you mean that woman? Or did you mean me?” Gorma asked, taking a bite of the cheese and munching the bread. The elephant did not know what to say, and stood blinking foolishly. And hungrily.

Oh, Gorma, Gorma, will you – how can I? – would you…share some food…with me?” And at that moment, the elephant looked more like a mouse than an elephant, very small, and willing to take the crumbs that might be offered.

“Of course,” Gorma smiled, and she broke the bread in half and gave him some, then broke the cheese and gave him some of this, as well.

“Wow – gosh – thanks – that was – on Myland Island –” he began, but Gorma simply said,

“You’re welcome,” and walked on.

Finally, as the day was wearing down and the evening began to cool the air a deep and lovely indigo, Gorma came to a fork in the road, a place where the path splits into two, and either way might be just the way to take you where you want to go. Gorma always loved a fork in the road, she stepped into the crossroads to read the sign she saw there. And who was sitting under the sign at the crossroads? Ben the Elephant. He was not trumpeting, or sputtering, or even squeaking.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, thank goodness you are here. The signs in this country are all written in the wrong language. I cannot read a word, so I don’t know where I am going. On Myland Island –”

And at that moment, Gorma began to read the sign aloud, to no one in particular, in the language of the Land of the Heart.

“You mean, this sign?” she asked, first in the language of the Land of the Heart, and then in Ben the Elephant’s language. He did not know what to say, so he looked back and forth, from Gorma to the sign, the sign back to Gorma, and then he looked down at himself, sitting in the dirt at a fork in the road. He looked up at Gorma, and his eyes understood, and it is just possible that his heart began to understand, as well.

“Gorma,” began Ben the Elephant, “oh, dear Gorma, would you please, if you have the time today, teach me a word or two of this language of the Land of the Heart? For if I do not learn, I will continue to lose my way, unable to read the signs at the many crossroads, and unable to hear the people, as well. This is how we live on Myland Island. But I would like to be changed by my travels in the world.”

Then Gorma smiled her best smile at Ben the Elephant. “Of course,” she replied, and as they nibbled on the last of the bread and cheese from Gorma’s bag, Ben the Elephant practiced saying the most important words he would need to continue his journey.

As darkness called to the owls in the trees and the bats in the caves of the rocky cliffs, Gorma stood to leave, looking down the lefthand path, of course.

Ben the Elephant stood too. “Oh, Gorma, Gorma –” he stopped himself, and smiling a very real and sincere smile, his best smile — “thank you,” he said, in the Language of the Heart. And he pronounced it perfectly, shaking Gorma’s hand very politely.

And Gorma simply said, “You’re – very – welcome.”

Then Ben the Elephant walked away down the righthand path, quietly practicing his new words so he wouldn’t forget. Because even an elephant sometimes forgets.

Gorma walked on, down the lefthand path, quiet and smiling. She arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. Outside, the night birds spoke each other’s languages with ease, twitter-a-twitter and whoo-whoo, whoo-whoo, softly greeting each other, and politely saying, “Good night.”

Buen Camino, Ben.

January 5, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

where will we walk

tomorrow

you and you

and you and I

where will the path

lead us

and will we follow

each our way

or simply

one another

The problem with my turtle pace was that I didn’t have a shell. By now, I was in excellent shape, strong and lean, and my pack no longer felt heavy. I was just…slow. Seventeen-year-old me saw a couple of ironic metaphors dawning, but I was too busy working this new puzzle.

I let others leave me in Camino dust each morning, knowing that by evening, we would all arrive at albergues, municipál or privado, near enough to see each other again the next day. But the Primitivo passed through less populated territory, with only a few villages between Oviedo and Lugo; it was not set up with as many options as the Norte. We were finding that due to favorable weather or historical significance, maybe the novelty or the physical challenge of this less-traveled route – whatever the reason, the Primitivo was feeling a bit crowded at the end of the day. The issue: not enough beds.

From Day One, I had decided to trust the Camino about where I would lay my head each night.

Intentionally disconnected from phone and internet service, I made no reservations. I carried no tent, having decided the extra weight was unnecessary with the albergue system. My light sleeping bag was comfortable and perhaps slightly too warm indoors, so my backup plan was always to find a chapel pórtico, protected from the elements on at least a couple sides. The Camino Provides.

Miraculously, it always had, even when what it provided was the pigeon-poop-sprinkled deportivo in Grandas de Salime. Having slept soundly there on the concrete rows of spectator stands, I now had no fear, bed or no bed.

Which was good, because I was…so slow. My friends carried deadlines like weight in their packs, cognizant consciously or subconsciously, tickets home with dates that were approaching faster than I was walking. They each had a limited number of days to reach their destinations – Santiago de Compostela, Muxia, or Finisterre – and were following their guidebooks’ daily stages to ensure they were able to complete the Camino.

I traveled in the ultimate luxury: no Time. Having scheduled 2-1/2 months for a one-month trek, I was free to change plans as the need or the mood arose. I had no job to return to. I had no house to make payments on. The Spanish summer stretched before me. At last, I had escaped the tyranny of the clock.

Only, I hadn’t. Not completely. The cheaper municipal albergues were first-come, first-served to peregrinos on foot. People pushed themselves, hard, to make good time, beat the crowd. When we arrived at the albergues, we set our backpacks in line at the door as proxies holding our places while we sat, boots off, in the shade nearby.

I found I liked the sitting and waiting. Part pleasantly-exhausted-mediation, part catching-up-with-your-neighbors-at-the-mailbox, it felt homey. If your backpack was far enough forward in the queue, you knew you had no worry, ensured a place to sleep. People just arriving consulted their guidebooks and asked the other peregrinos already sitting and waiting, “How many beds here?”

More calculus. I wasn’t interested. I didn’t do the headcount. I didn’t care. Again, a good thing, because I often just barely squeaked in the albergue door. For the second time now, I had gotten to register with a hospitalera only because I had shown my sleeping bag and said I was willing to sleep on the floor. The first time, a cancelled reservation became my bed. This day, I waited to see, my fellow peregrinos offering sleeping mats or suggesting the common room seats would make a good bunk for me since I was small. Time would tell.

Now that the Primitivo was short on municipal albergues, older or slower pilgrims routinely called ahead for reservations at the private albergues. I began to read the writing on the wall, sometimes actual handwritten paper signs taped to the doors: completo. Speed was of the essence, and I had left speed behind, thousands of miles across the ocean in the rat race.

Before I came to Spain, I had not given much thought to how unique each person’s pace really was. It had seemed like a matter of fitness and fearlessness: out-of-shape or timid people seemed to walk slower, at work, down the sidewalks. “Mallwalkers,” I derisively named them. I would either nearly bump into my coworkers as I hustled to my tasks, or look for a sidewalk passing opportunity on my way to coffee or an errand destination. Back home, I walked as if 17-year-old me was driving.

I was not enamored of driving; once again, a bad American. While my high school friends had rushed to get their driver’s licenses at first light on their 16th birthdays, I was reluctant. I stalled. Even though I got to school and work at the mercy of the elements, I preferred walking and biking. I loved that slower pace and smaller size in the world. And I did not love the effects of vehicle traffic – the noise, the smelly clouds of exhaust drifting in the air behind them, the splash of icy gutter slush as they drove past me, and most of all, the speeding danger.

For years, a ton of steel hurtling down the road under my command gave me nothing but an ominous sense of responsibility for impending doom. My older sister had once slid on a curve while driving, rolling her car off the country road and into a field, finally crawling out the window of the upside-down vehicle.

As we were driving back from lunch one day in high school, my friend hit a dog that ran into the street; it had no collar or tags. He knocked on nearby doors, but no one answered. Finally, not knowing what to do, he laid the dog in the grass beside the street, and took us back to school, all of us in the car shaken and disturbed.

I took my father’s highway patrol stories to heart. Many years ago as a state trooper, he had seen merciless accidents, his cautionary tales only skimming the surface of horror stories of drunk drivers, semis barreling down the interstate at high speed, and in one nightmare, a traveling family all decapitated by the terrible impact that drove their car underneath one of those massive trucks.

But social expectations are a terrible force, as well. In those days before bike commuting was commonplace, I was weird. Classmates teased me, laughing at my bicycle, a secondhand road bike I’d had to buy myself with money I’d earned. So just two months before I turned 18, I finally took my driving test, and got my dreaded license. My birthday is in the winter. Armed with my new license, I took my little sister for a ride to go sledding…and slid right into a parked car instead.

It was the spinout on black ice two years later that changed everything. Driving home on a chilly spring afternoon after a recent snowfall, the streets looked clear. But hidden beneath front yard trees of homes along the road, black ice lurked unseen in the shadows, like a mountain lion ready to leap. I remember the slow-motion spin, smoothly and painlessly arriving on someone’s lawn, facing backwards, somehow having miraculously missed every tree. But all I could think about was my belly.

My baby. I was five months pregnant.

After that – I learned to drive. Really drive. I learned to spot potential driving hazards like babyproofing my house for choking hazards. I became a student of correcting a spin, pumping my brakes, downshifting, precise lane changes. I took command of the road, utilizing my best-honed skill to perfection: trust no one. No driver, no turn signal indicator, no rules. Driving was insane; I became Mad Max.

I still didn’t enjoy driving, but I had become fearless, because I had learned defensive driving. I always had the backup plan, the evasive maneuver, figured out ahead of time, just like my dad had tried to teach me. And it worked. I went from fender-benders to a flawless driving record. No moving violations. Just a propensity for speed.

On team sports you learn, “The best defense is a good offense.” On the road, that’s driving with the flow of traffic – literally keeping up with the Joneses in their big, fast car. Accidents often happen when people are frustrated and, just like in sports, impatiently make a bad pass. By driving the same speed as everyone else, no one needs to pass. Everyone arrives relatively unscathed.

Except that the essence of American driving is the essence of sports: competition. Competitive drivers always reach in for the ball, namely, that one position further than where they currently are, just ahead of this guy, whom they tailgate, flashing their headlights as if the highway speed limit signs now read “Autobahn.” The Great American Open Road was filled with aggressive maniacs who had never heard any of Dad’s highway patrol stories.

So once I’d mastered the interstate speed madness, had figured out the Freeway Weave of downtown drivers constantly jockeying for lane positions during rush hour, had learned to escape an intersection aptly named “The Mousetrap,” I took my own exit: I learned all the back roads.

I learned which dusty country lanes led to my favorite canyons. I followed numbered county roads into the mountains whenever possible. I wandered dirt tracks into the hills. I escaped, I parked, and then I hiked.

Hiking was often an all-day affair. Whether I had the kids with me or went by myself, I planned for the day – and then I let go. With a backpack of food, water, and emergency supplies, I taught my kids what I had learned from the hay fields and the wide sky of my youth: Time is only a description of Life. We hiked kid-speed, rambling and running, stop and go, noticing pine cones and chattering squirrels, water trickling beneath ice in frozen riverbeds, Indian paintbrush and columbine blooming beside trails.

When I went alone, I relearned the lesson of Time, deeper with each outing, like the ancient Pueblo people’s footprints over centuries wearing a knee-deep track through stone to reach their cliffside homes in the desert Southwest: it was the act of living, the taking of the steps, that created the path. Time only summarized, never able to fully explain this miracle of stepping through solid rock, because the miracle was in the purposeful path, chosen again and again.

Speed was pointless. The miracle was the flow of Life, which just happened to be moving across time. Time was just a backdrop – the Play’s the thing.

By the time I hit the Camino’s dusty trail so many years later, I just shifted into hiking mode, stepping into the flow, watching the sun’s passage across the sky, the cloud build-up, the shadows, as my way to measure the hours. I wore my old Timex watch, just like I always did hiking, its purpose still to show if I was technically too late, at home to swing by Bob & Tony’s Pizza after the day’s hike, now here, to get into an albergue.

Yet just like back home, I didn’t really care. An albergue had become like a pizza – a nice indulgence but not necessary. What mattered to me was the Life that Time was describing around my footprints. I had been so worried as I boarded the plane for Spain, afraid that too many years had gone by, my dream fading; but I wasn’t too late – because I was alive, and I was doing it.

I was so alive. On the Camino, I was living every day, not chasing the dream. This was a live performance, unscripted. To Be or Not To Be. And I had long ago decided to Be Here Now.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As I walked along in the afternoon, I met Bruno of Paris, probably the most charming man I had ever met in my life. Unassuming and stunningly beautiful, his eyes twinkled with a child’s mischief, though his dark curly hair was salted with the first beginnings of age. A middle-school teacher and administrator, he was the perfect man for the job, Peter Pan meets Pied Piper, as his sense of humor and easy affection led those young ones, who still scampered between life passages, forward into each new day. His voice was melodic, his French accent almost a trope if it hadn’t been so endearing. When I asked about Paris, his response was, “But you must come! You can stay with me. It is of course the most beautiful city in the world. It is Pa-rie.” He repeated his invitation later, his graciousness easy to accept, offered with the nonchalance and friendliness of a man who knows who he is – who is at home with himself.

This was the pace I kept seeking and maintaining, almost defending, the pace of noticing, of contemplation, of laughter and friendship, of listening for songs like listening to the stories of people I met along the way. And for me, it was slow. Slowing my feet had slowed my mind and opened my heart, so that I could finally hear words of wisdom and advice from others, so that I could pay real attention, or ask for what I needed, and so I could ultimately, finally, see that everything I needed, I had.

As Camino bedrush madness swirled around me like rush hour traffic, I now pulled into the even slower lane. Having tried to find Joanna, Christoph, and Cordula in one busy town, by luck I ran into Felix, and gave him a message to relay if he caught up to them: go on without me. I am walking my slow way into Santiago. Buen Camino.

I waited at the bar beside the albergue. Softly, in walked Mauro, who gave me a sweet hug and bought me a glass of wine, and we lingered on a bench out front, cuddled together comfortably, watching the sunset.

The hospitalera, who ran both the albergue and the tavern, came by to tell me she had a cancellation, and had a bed for me. I told her she could give it to the German woman who was also waiting for a bed, because she was older than me. I got a big smile, later a free chunk of bread, and on into that evening, an approving pat on the knee as the hospitalera walked by. I also got a bed, from a later cancellation.

As the night grew cooler, I hugged Mauro goodnight, and took my bread in to the albergue kitchen.

“Would you like some of this soup?” It was Bruno, sitting with another man at the dining tables.

This felt like the blessing of slowing down, finding sheltering chapel pórticos every night disguised as bars and albergues and warm benches between, welcomed by patron saints and guardian angels who looked remarkably like very beautiful, everyday people.

I soaked up these moments of affection like bread into warm soup, softening.

barbwire passing across an immense boulder between two fence posts, along the Camino Primitivo

December 21, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

he did not want to serve me

signs were all there

no boots

no packs

filthy pilgrims

tracking mud and sweat

into his bar

but finally

cafe con leche

I warm my wet hands

at the corner table

look at all the faces

in the photos on his walls

friends music

family laughter

he sees

I take my empty cup

back to him

buen camino

he tells me

with the softest smile

Day of rest. Because sometimes the Sabbath has to happen on a Monday. Walked 9 km to a small town, Castroverde, boasting a shiny new albergue with no kitchen towels or utensils, but many flies. So it goes sometimes. But I was third to get a very clean bed, so this was a great day.

I waited for the albergue to open by having coffee and a chocolate-filled croissant and writing my postcards. Once checked in at the albergue, I mailed the postcards for the weekly cost of 6.75 euros, the price of a bed – then went back to the cafe and paid for my breakfast, which I had forgotten to do. We had teased Joanna relentlessly, “Remember to pay for your food!” because she once forgot; Francesca had copped to it, too. So now it was my turn. No such thing as a free lunch.

The hospitality of Spain took some getting used to. I had been quite confused by it, at first. Whether I ordered a full Menú Peregrino, a bocadillo, or just a cafe con leche, from a table or walking up to the bar, I was nodded to – and then left to study my map, enjoy the view, or strike up a conversation. Every time was like a white-tablecloth affair, even just a coffee: my order was brought to me, but I didn’t have to pay immediately. And a check rarely came – most times, I had to initiate payment. And remind the barman what I had ordered. The honor system.

Coming from a world of ordering and paying at the counter, it was easy to forget to go back. At home, you had to order fast, pay fast, and often took your order to go, especially on a Monday morning. But the bars in Spain were filled with men drinking coffee and and talking politics and sports; the markets were jammed with women comparing prices and stories. Payment took second place to meeting up with your neighbors, catching up on family, discussing the world. My take on Spain was that this very traditional society was built on talking face to face, side by side.

Loudly. Bad manners, to yell your political ideology at a coffee shop back home; making your point, in Spain. Seventeen-year-old me glanced up and then smirked over my notebook, pleased to be the quiet one for a change, a spy in the house of love, “gathering clues to be used in the war of the affections.”

I’m on your trail

you’re never alone

one day you’ll slip up

and leave a lip print on a coffee cup

— Was (Not Was), “Spy in the House of Love”

I stopped this morning in Vilabade, and locals opened the 15th-century Church of Santa Maria for us, the peregrinos chatting and taking a rest together in chairs set out beside a food truck.

I loved the churches. I loved the archways, I loved the crazy, colorful, gilded over-the-top altars, I loved all the statues of saints carved in wood and polished smooth as satin, I loved the creaky wooden pews.

I loved the darkness, and the quiet. I loved the windows way up high, that let the morning light filter in. I loved that songs had been sung here since 1457.

muchas gracias, Amigos del Camino, for opening the church

The patron saint of this church was Santa Carmen, protector of sailors and ships, landlocked here, nowhere near the sea. I thought of the ship of stone, waiting at Muxia. I remembered hurling my burden stone on the mountaintop, and wondered about the Camino stone I still carried beneath my water bottle. I felt attached to it, like I carried it for a reason; I just didn’t know what that reason might be, yet.

Tucked away along the side aisle stood Santa Barbara. As always, she was portrayed with strawberry-blond hair, like mine in my youth, dressed all in red. I liked her as the Lady in Red, the color of blood and fire and passion. Typically portrayed carrying the tower where she had been imprisoned (now reduced to the size of a doll’s house), she stood holding the sword that had been used to cut off her head. She claimed the symbols of her suffering as her raison d’être, literally her reason to be, moving beyond them, a self far too expanded to be contained now, powerful enough to take back the weapon of her own destruction.

I marveled at her. “This is Santa Barbara,” the local woman told us.

“Yes, and this is Barbara, our Barbara,” Christoph had said beside me, smiling broadly. “We have our own Santa Barbara.”

Trail-named. An honor. I had been called out to by this name, from restaurant patios and albergue doorways, seeing Joanna or Christoph or Felix laughing and smiling as they did so, but never so christened as in that moment, before the statue, in the church.

I had always hated my name, prior to the Camino. A harsh-sounding Greek name, it meant, “a foreigner, a wanderer, a stranger in strange lands.” It had only confirmed my feeling as an outcast. To make it worse, to me, it had always sounded like the unattractive name of a middle-aged church lady with bad hair and bad clothes. Which is exactly what I was just then. My crewcut had grown out into a wavy mop that I tamed with my Basque-earring’d hat, my hiking clothes utilitarian and not particularly flattering. No flowing red robes, my sweaty tanktops. No more golden mermaid hair of my younger days; this Sampson had met too many Delilahs-in-disguise, so I’d chopped it off myself, hoping to avoid being noticed any more.

But like my bushy hair, I was trying to grow into my name. I had decided to embrace “The Wanderer,” reclaiming my birthright, before I left home. Wanting to write again, I had created a website where I could chronicle my great escape plan, posting essays describing my thoughts and feelings as I contemplated making a break for it, ditching the ivory tower of the American Dream for my own personal dream: to see the world, and write about the world’s people.

A lover of Pablo Neruda, the great Chilean poet, I named my site after my favorite line, his words etching themselves across my heart:

Our love is like a well in the wilderness where time watches over

the wandering lightning….

— Pablo Neruda

I wanted to live that poetic image, write about the instances of synchronicity in our lives, those moments when we are thunderstruck by understanding, finding and drinking from that deep well where we learn to care more deeply…because we are connected.

I named my website “wandering lightning.” Having purchased the domain and set up the site, on a hunch, an intuition, I felt drawn to look up a translation of my name. Not my first name – my middle name, Lynn. I’ll never know why I decided to look it up; it had always been a bland segue between my irritating first name and my honorable last name, the name of my Viking forebears from Denmark. So I was shocked, spooked, and thrilled to find out that the Danish word “lyn” – was the word for “lightning.”

My name was Wandering Lightning.

In Spain, I learned that, having been burned, Santa Barbara just happened to be the patron saint of trial by fire. And of lightning.

gathering clues to be used in the war of the affections

I’m a spy in the house of love

I won’t be refused

I’m waiting for your heart’s defection

— Was (Not Was), “Spy in the House of Love”

Santiago Matamoros is the warrior incarnation of Saint James. A folk-hero fiction of the Reconquista, he is typically depicted making a great leap astride his white horse, his sword raised in the midst of battle.

December 21, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

- Hike from 7am to 4pm.

- Dig into your pack for your food bag.

- Find an unfinished package of dried apricots.

- Eat most delicious apricots ever.

- Apricot Surprise! buen provecho

December 15, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Then, in that hour of deliverance, my heart spoke. Does not such a country, and such defenders of their country, deserve a song?

— Francis Scott Key

A day rich in weather…fog, mist, water in the air and underfoot on the trail. All day, I walked writing a song. Svend should have seen me go under my hood, a student of my previous day. By the time I reached A Fonsagrada and Podrón, the song was leading me.

Joanna had told me yesterday that she envied my ability to change my life. She said it was not so easy in Poland; many choices, like returning to college, a career change, were subject to approval by governmental agencies. I had no idea. She said she was only teaching now by a miracle, a new private school that worked with her on taking certification courses. If not for this unique opportunity, she would still be in her old, miserable job. “Many people in Eastern Europe see America as a land of this opportunity – to become who you wish to be.” Even if I didn’t always behave like an American, I clearly saw that I thought like an American – entitled to be free.

Free to do whatever I damn well please. I gave 17-year-old me a stern glance. Released is not free; it is unmoored, unchained. Unless I chose to rise, I would just remain forever adrift. Homeless.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As I neared the albergue, a cab pulled up in front of it, and three peregrinos hopped out, pulling backpacks from the trunk and hustling inside. I quickened my pace and stepped in at the door behind them.

All three were haranguing the hospitalera, who was becoming overwhelmed and frustrated. She saw me at the door, and I approached her desk, saying quietly, “Buenos dias; cama por uno persona, por favor?”

“Uno persona?” she confirmed. I nodded, and she waved me in, past the arguing cab riders, who threw a new fit as I followed her up the stairs. Apparently, they didn’t know that pilgrims who arrived by foot always had precedence over pilgrims arriving by vehicle, in the municipal albergues; no reservations accepted.

I was escorted to the last bed in a room for four people. And who did I find in the other three bunks? Cordula, Christoph, and Joanna. Surprise and delight filled the room, and filled me. I had arrived just in time to go to mass, where the priest would give a Pilgrim’s Blessing that night.

I sat next to Christoph as the service began. The mass was beautiful, simple. At the end, the priest called all peregrinos to join him at the front of the church. We stood before the small congregation, while he blessed us all – the jerks and the arrogant, the cab riders and the song writers, the beautiful souls and the wise map makers and the ones who would be monks. The psalm the priest chose for us he called Pilgrim’s Psalm, in fact the 23rd, which included images of being led beside still waters, and guided along the right path. “You have prepared a banquet for me in the sight of my foes. My head you have anointed with oil; my cup is overflowing. Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life.”

I thought of the pilgrim’s dinner before the Hospitales Route, our cups overflowing with wine, a banquet prepared without my having to plan a menu or lift a finger, everyone invited. I knew that the anointing with oil was an historic Jewish rite denoting a chosen king, interpreted as a personal blessing. I remembered my blessing on the mountaintop. Goodness and Mercy were doing their best to follow me, but I was ducking them at every opportunity.

I tuned back in as the priest gave us his Pilgrim’s Blessing: “…Help these pilgrims on their way to Compostela. Guide their footsteps with your kindness. May your shadow protect them during the day and the light of your eyes shine on them by night, so that they can happily stand before the tomb of the Apostle Santiago.” My printed translation of the blessing began with the typo “Lord Good.”

Lord Good. It touched my heart as we stood, pilgrims all together, for endless photos, the priest happy to take a picture for each peregrino with their own cell phone camera. Nonetheless, I did not hand my phone forward. I held the moment of blessing very close, trying hard to remember it. I didn’t want a picture. I wanted this blessing to leave an image of itself within me, forever. Plus, having my picture taken annoyed me, and I just wanted that part over. I was tough to bless.

Even so, afterward, an elderly woman with a palsied face reached out to me. A member of the local church, she had stayed, sitting alone in the pews while we had our pictures taken. Why she reached for me specifically, I could not say. She took my hand, then my face, and kissed both cheeks, saying gently, “Buen Camino,” then kissed me on the forehead, one last time. As she walked out, she turned and blew kisses to me, out of sheer love.

In my case, maybe for luck, as well. “Good Way,” she’d blessed me. Basic Goodness: I wondered if

I could actually learn that meaning of Life this time. Apparently, I needed a lot of repetition for the blessing to stick with me.

Christoph had given me excellent words of wisdom about “my American” dilemma. We agreed that we detected a certain loneliness in Ben, that he seemed desperate at times, and quite sad; being American just added a layer of awkwardness and blundering. “I think he is doing the best he can,” Christoph had advised me, kindly.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I walked arm in arm with Joanna back to the albergue at the end of the evening. As we came upstairs, I saw Ben taking off his boots. “Hey,” I said softly, without hostility, giving a little chin nod, the quintessential American greeting. I tried hard to put that light into my eyes, to shine some kindness his way, here in the night. He was caught off guard. Close enough, I thought, walking on to my room.

Joanna was now stretched out on her bunk. “I wrote that song, about your sad burned trees around the long lake,” I told her. “Do you want to hear it?” She was all ears. And adorable smile.

in my mind today

I must find another way

where the trees that were on fire

bloom with butterflies and briar

where the walking is the day

where the journey is the way you walk it

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

on my wall there hangs a shell

reminding me to walk it well

unexpected twists and turns

the mint is sweet, the nettle burns

between the mountains and the sea

every shrine and every chapel a cathedral

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

— “El Camino”

“Oh sing it again – I want to record it!” Joanna cried, pulling out her phone. I sang it again for her, my enthusiastic audience.

“Do you want to hear another?” I asked, laughing.

“Oh yes!” she said.

From the next room, a loud rustling of unpacking could be heard, interrupting our recording session. “Shhh,” I heard, “Barbara is singing. Be quiet.” I looked out. It was Mauro in his bunk. He told me he loved my voice, and to please keep singing. I think I sang him to sleep; he was feeling sick, so maybe in this way I passed my blessing on.

A Fonsagrada – “To The Sacred Fountain.” The legend we heard was that Saint Francis, himself on pilgrimage to Santiago, had gotten sick and stopped there, cared for by the locals until he recovered; in return, he had blessed their fountain, and it ran white with rich milk to feed them. A banquet, their cups overflowing.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

“Oh no! I missed it!” was Christoph’s response when Joanna later told him I sang for her.

“Don’t worry,” I told him, looking up from my notebook atop my upper bunk perch, “we can sing again; singing is fun.”

And I was dumbstruck to hear myself in that moment – singing is fun. Why had I never said this before? Performance anxiety, I supposed. A hundred small disappointments, I lamented. Singing was my mother’s claim to fame, not mine, I backpedaled. Well, not any more. Listening to myself along the trail, I had heard an echo of my mother’s rich alto voice rising in my 51-year-old throat. Her unintended gift to me.

I looked out the small window at the stars, and was thankful for the gift of singing: music, welling up within me like a fountain, everywhere I went. The perfect instrument for my poetry. The Pilgrim’s Prayer had concluded with, “May we joyfully end the way that we are trustfully doing now.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As I walked along, late in the morning, I heard a familiar voice behind me: “Hola, Chicka!” I turned to see Francesca striding down the hill behind me, which quickly rose again in a new hill, the rolling stroll we had entered now in Galicia. I ran back down and met her in the hollow, and we hugged tightly.

“I thought you were going to walk the Norte!”

“Right, that was my plan, but then I so wanted to do the Primitivo, you know?” Francesca had been walking long days, over 30 and 40 kilometers daily, trying to find beds in the limited number of albergues on the Primitivo. Still, we were so happy to see each other, to walk together again for a few hours, to hear each other’s stories. She was delighted to hear I was writing songs; I had missed her London sass.

As we packed up from our lunch break, we were joined by a most unlikely third wheel: Ben. I introduced him to Francesca, who eyed him suspiciously upon hearing that he was an American. She had just told me, “Your countrymen are not doing much to disavow the stereotypes of Americans abroad. In fact, you’re the only one I like.”

We set off down the path together. Because I had been kinder to him in cafes and albergues, Ben now bravely struck up a more real conversation. “I heard you singing the other day; that was really good. Is that what you do? Are you a singer?”

“You mean on stage? I have, in the past.” I looked over at him. “But it doesn’t pay anything, unless you give up your whole life to travel around, go on tour.”

“You don’t do that?” he asked.

“No, I have a family, so I found a day job instead.”

“So what work do you do?”

I remembered answering this question when I took my oldest daughter to her college Freshman Orientation. We were sitting at a table of other parents, and I remembered their faces, and my daughter leaning over to me after I answered: “Way to kill the conversation, Mom.” It was true; the parents didn’t talk to us after I told them.

“Did. I used to work with homeless people. We had a community resource center where people could come to eat, take showers, get their mail, lots of support services.”

Ben didn’t bat an eye. “But you don’t do that any more?”

“Nope. I decided to do this. So I quit my job, sold my house, and bought a plane ticket to Spain.”

Now Ben batted an eye – both of them, blinking in shocked surprise. “You sold your house? I mean, most people in America, they wouldn’t….”

“Yeah, I know. I’m a bad American. I gave up everything I owned. Well, except the jeep.”

“Well of course not the jeep,” Francesca chimed in.

“Right,” I agreed.

“Wow,” Ben replied, clearly considering this new information. “So you sold your house – but you have a family?”

“Yeah, but they’re grown people. They have homes of their own, now. Except my youngest son. And he’s in high school; he’s living with his father.”

Ben was thoughtful for a moment. “I can’t imagine doing that. My wife and daughter wouldn’t go for that.”

“Most Americans wouldn’t go for that,” I agreed.

He was a dad; I smiled. Ben talked about living in San Diego, the cultural pressures to live in the right neighborhood, send his daughter to the right school, those dinner party conversations about the work you do. He was feeling particularly boxed in by work. Francesca and I listened.

Ben asked about the work of the resource center. I told him how we ran it, the programs, having to ask people to leave for the day if they were intoxicated or behaving in ways that made others feel unsafe.

Ben pounced on the idea of homeless people being alcoholics. Francesca immediately explained that didn’t apply to everyone.

“So many issues contribute to homelessness,” she countered. “You don’t become homeless just because you drink, or you lose your job. You become homeless if you lose your job AND have no money in savings AND have no network of people to help you until you find another job.”

I agreed. “Homelessness is a house of cards. It’s not very solid to begin with, and then any combination of crises brings it tumbling down.”

Ben asked lots of questions about homelessness, and seemed to be learning. I taught him that he can’t say “those people” about anyone unless he wants to engage in unhelpful stereotyping. He got it, that it was a phrase of judgment and distancing, a tool for alienation, and even hate.

Whoever teaches learns in the act of teaching,

and whoever learns teaches in the act of learning.

— Paulo Freire

Francesca and I got a glimpse of the impact when he casually mentioned having served in the Israeli Army, when he was younger and living in Israel. It didn’t matter in that moment what our politics were: we exchanged a glance, imagining this simple guy not more than a boy, carrying a gun, facing war with the Palestinians; this Jewish man trying so hard to fit in and gain acceptance in his San Diego neighborhood, in sunny blond Southern California. America the Beautiful.

oh say, does that star spangled banner yet wave

o’er the land of the free

and the home of the brave?

— Francis Scott Key, “The Star Spangled Banner”

Just before we parted ways, feeling comfortable and trying to be funny, Ben made a comment on something Francesca and I had just said, tagging in with, “Women!” And I did not eviscerate the man with my titanium camping spork, nor did I allow Francesca to gouge his eyes out.

“Ah – ah – ‘Those People!'” I reminded him.

“Hey, you’re right!” he responded in total surprise. And to my total surprise, we all got to laugh together, before waving goodbye.

As I walked on, I remembered a quotation I had once written on the whiteboard for ArtSpeak: “Every blade of grass has an angel that bends over it and whispers, ‘grow, grow.'” It was from the Talmud, one of the beautiful, poetic holy scriptures of Judaism.

Before I reached the albergue, I had written another song. Mostly, it was about my kids, about what it felt like to be a parent; it’s also a reminder to myself, to look past people’s fears and find that sacred spark of light shining in every person, sometimes tucked away into a hidden, secret place, watched over by the whispering angels of Lord Good, and the Tree of Life to which we all belong.

every blade of grass

has its angel bending low

whispering so soft and low

grow…

every falling star

is a dream I dreamed of you

how I wished you would come true

glow…

Life takes hold and Life moves on

learns to walk and learns to run

but I’m still whispering to you

grow…

shoot your arrows to the sky

spread your wings and learn to fly

climb up strong and climb up high

grow…

you’re the sun and you’re the moon

all my harmonies in tune

starlight woven on a loom

you glow…

Life takes hold and Life moves on

learns to walk and learns to run

I’m always whispering to you

swim your waters that are blue

build the fire that is you —

your life’s a dream that has come true

and you glow

— “Every Blade of Grass”

December 15, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

The Camino that can be measured

is not the Camino.

The Camino that can be mapped

is not the right road.

The Camino is not a road;

The Camino is a way.

Free. This Moses came down from the mountain and checked her tablets of wisdom at the door, rejoining the dysfunctional emotional bacchanal already in progress. Golden calves come in many forms – and there’s nothing like a gilded mirror to catch your eye and help you take a good look at yourself.