January 29, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Roughly 150 demonstrators greeted travelers Sunday afternoon as they emerged onto the Westin Plaza at Denver International Airport. Holding signs reading, “Diversity is our Strength” and “We the People welcome you,” protesters chanted, “No hate, no fear, refugees are welcome here.”

As multiple federal courts issued orders to temporarily stay the president’s executive order banning all refugees, as well as citizens from seven Muslim-majority nations, from entering the U.S., immigration attorneys have been mobilizing to gain access to travelers who may be detained currently in our nation’s international airports. Local members of the American Immigration Lawyers Association responded to alerts from the International Refugee Assistance Project. According to Denver attorney Christina Brown, approximately 20 immigration lawyers were at DIA on Saturday; on Sunday, more lawyers arrived as word spread through Facebook and email groups.

One of Sunday’s arrivals was Jennaweh Hondrogiannis, a private immigration law attorney. When asked about coming to DIA on the weekend, Hondrogiannis responded, “This is the work we do. When we’re needed, we’re here.”

Laura Lunn, a managing attorney with Rocky Mountain Immigrant Advocacy Network, and private attorney Kristin Knudson volunteered with the newly-formed DIA Pro Bono Legal Project. They explained the difficulty with helping immigrants and refugees to access their rights under the current executive order. People wanting to enter the U.S. “who assert a credible fear or a reasonable fear have a right to be interviewed,” noted Lunn, referring to a credible fear of persecution or torture if the person were to return to their home country or country of last residence. According to Knudson, the “credible fear interview” is to determine if the person may be eligible for asylum. These interviews are conducted by asylum officers of USCIS, known commonly as Immigration Services. Immigrants have a right to legal representation when seeking asylum.

Lunn explained that the current executive order is focusing on the “expedited removal process” for immigrants, which immediately returns people with “no expressed fear” to their country of origin. The problem, according to Knudson, is that refugees without legal “refugee” status often don’t know they have a right to speak up about the dangers that caused them to leave home. Lunn stated, “They don’t know the magic words that could open the doors.” U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers (CBP) of the Department of Homeland Security are supposed to directly ask immigrants why they left their home country and if they have fear or concern that they would be harmed if they returned home. At issue is the lack of access to legal counsel within this process, as immigrants are interviewed without having an attorney present, and may feel unsafe or unsure about what to say. People with legal “refugee” status have already been deemed unsafe to return to their home countries and determined eligible to enter the U.S. But now their entry is being blocked.

The attorneys at DIA said they have no way to know if the appropriate questions are being asked. Ordinarily, immigration attorneys call in to CBP to advise officers that they are on-site and wish to see their detainee clients. Now, no one at CBP seems to be answering their phone calls.

In addition, U.S. residents have been caught up in the expedited removal process. Citizen advocate Marcela Mendoza spoke up among the attorneys lined up in front of the International Arrivals gate at DIA. “The executive order is so overreaching – it included people with green cards,” she said, meaning people with lawful permanent resident status. “That’s why the ACLU filed a writ of habeas corpus in New York – but Homeland Security won’t follow it.” That court petition for writ of habeas corpus is Darweesh v. Trump, and includes the following statements:

“After conducting standard procedures of administrative processing and security checks, the federal government has deemed both Petitioners not to pose threats to the United States. Despite these findings and Petitioners’ valid entry documents, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”) blocked both Petitioners from exiting JFK Airport and detained Petitioners therein. No magistrate has determined that there is sufficient justification for the continued detention of either Petitioner. Instead, CBP is holding Petitioners at JFK Airport solely pursuant to an executive order issued on January 27, 2017.”

A young black woman, Z., sat holding a sign for the DIA Pro Bono Legal Project, the name of this ad hoc congregation of Denver attorneys. She wore a nametag labeled, “Legal Monitor,” as all the volunteers with the project did. When asked why she had volunteered, Z. replied, “I am refugee. When I hear this, I feel bad.” She has been in Denver a little over six months. “Refugees – most of them are starving, most of my family are there. Maybe when they come here, they find peace.” “There” is Congo in east Africa; Z. said she left to escape war. She said the African Community Center in Denver helped her get her local identification documents when she “came with legal papers,” and also helped her find housing in Aurora.

She is still haunted by her journey, though. “Father not come – day of departure, his visa still not arrive, so we leave without him.” She and her sisters were 19 and older, so they were allowed to go. “Mother, we lost her, in the war. We don’t know if she alive or die. Lost her. Lost.” Z. tears up but maintains her composure. “Refugee story is bigger – is bigger story.” She smiled again, and turned with her sign. “I can’t fight against government. Our neighbors, Sudanese, they are starving. If I have possibility, I can make the peace.” She paused, then added, “I am Muslim.”

Behind her, attorneys shared updates. “Do we have a name?” “We have a birthdate.” Christina Brown noted, “No word yet, though.” Lunn added, “CBP won’t talk to us, won’t take our calls in there. We spoke to colleagues in D.C. – this is happening at all the airports.”

January 29, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I parked in the REI parking lot, and walked toward the faux-chalet entrance mulling the pros and cons of water tablets versus water filtration for my next long backpacking trip.

Ahead of me, a very tall, very big, older white man walked toward the store, decked out in shiny, new hiking wear and the aviator sunglasses beloved by men of a certain age. He was imposing; I’m pretty sure he knew that.

He opened the door, and held it open for me. But I was putting my phone away in my pocket, so I said, “That’s okay – you first.”

He looked down at me and said, “After you.”

I stopped, squinted a bit and said, “No thanks, go ahead.”

He paused, almost smiling in that near-sneer some men do, looking down at me through those mirrored aviators, and said calmly, “After you.” He had not moved a muscle.

I got that angry chill up my spine and neck. I looked him full in the face and said, “No thank you.”

He did the doorman arm gesture of slowing ushering me inside, and pronounced, “After – you.”

“No – thank – you.”

We stood, in the entryway of REI, locked toe to toe and eye to eye. Well, eye to mirrored aviators. Neither of us had raised our voices. Neither of us had taken a step. But he just could not stop. He actually said it again.

“After you.” It felt menacing. It sounded icy cold. It reeked of control and power.

So I took a deep breath, cocked my head, and said, “I can stand here all day, friend.” The smile twitched in the corner of his mouth, but then an REI employee approached. The big man turned and went inside. As I opened the door, the employee was saying to him, “Standoff in the doorway, huh?” and glanced at me with surprised eyes. Not exactly nervous eyes. Or worried. Or even concerned. Possibly, just possibly…slightly embarrassed. But you can never quite tell. It’s hard to read someone’s eyes.

Especially behind mirrors.

Such chivalry afforded to the weaker sex today. Heartwarming.

Here’s a tip, for all the confused authoritarian patriarchs out there wondering what’s gotten into the little women lately: we see you. You’re a sham. Smoke and mirrors. Fakes. Frauds. Your spinelessness shows in your bullying of people smaller, poorer, less empowered in the world you strut through.

We are the authorities on our own existence. We decide about ourselves – about our bodies, about our rights, about our options.

About which doors we will go through, and which doors we will not. We have the power to open our own doors, for ourselves, like other men you do not hold doors for, gritting your teeth to say, “after you” to them. We are your equals. And our eyes are wide open to how we have to stand up for that fact. In the most ridiculous places, in the most tedious ways.

Chivalry can die; the King is dead. Long live actual Equality instead.

January 22, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

“Tell me what democracy looks like — THIS IS WHAT DEMOCRACY LOOKS LIKE! Tell me what democracy looks like — THIS IS WHAT DEMOCRACY LOOKS LIKE!”

“Tel

Louisa May Alcott took to the streets for women’s rights in the 1870’s, going door-to-door in Concord, Massachusetts, to secure the right to vote. She was with us again in spirit yesterday, January 21, 2017 – all over the world, to secure the right — to Be.

I read Little Women as a girl in 1970’s Iowa, identifying with tomboy Jo, who was of course Louisa herself. Louisa had younger sisters, as I did; an older sister, and I had several. She not only admired the writings of Henry David Thoreau, as I did, she knew the man himself, and spent time at Walden Pond learning botany and most certainly ideas about civil disobedience, as well.

I like to help women help themselves, as that is, in my opinion, the best way to settle the woman question. Whatever we can do and do well we have a right to, and I don’t think any one will deny us. — Louisa May Alcott

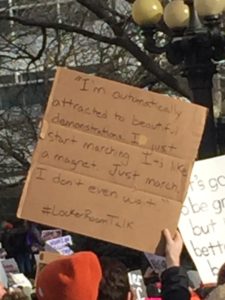

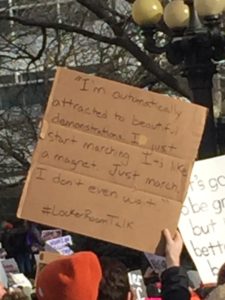

Oh, but deny us they do. With the election of Donald Trump, “the woman question,” which we thought to settle with the election of Hilary Clinton, became an open wound of outrage and despair as a self-confessed sexual predator placed his tiny, “pussy-grabbing” hand on an actual bible and swore to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” The flesh-and-blood citizens of the United States, well, good luck to you. And me.

You have a good many little gifts and virtues, but there is no need of parading them, for conceit spoils the finest genius. There is not much danger that real talent or goodness will be overlooked long, and the great charm of all power is modesty.

See, the thing is, Louisa, we are pretty concerned that there is in fact a clear and present danger of all our talents and goodness being not only overlooked but attacked, systematically, since Conceit took office. So when my youngest sister asked if I wanted to go to the Women’s March on Denver, I said yes immediately.

I don’t do protests. I write what I want, and say what I feel, which is how I have justified the fact that I don’t do protests. All my life, I have seen protest marches as naive and smugly self-serving, an act of conspicuous righteousness that later falls away into a return to the status quo. The truth: I am cynical that walking a parade route will change anything. But this year, it is different. This year, the certainty of oppression and abuse is undeniable. And I have daughters now.

Women have been called queens for a long time, but the kingdom given them isn’t worth ruling.

Oh, Louisa, my girls are indeed fabulous. Not in terms of fashion and hair and pageant-worthiness, though they are spectacularly beautiful to see and hear. We three together scoff and laugh at being judged in Conceit’s shallow terms of women. My girls are true women. They scale rock faces and mountains and travel between continents and love Gloria Steinem and leap into the unknown waters of their lives from the high cliffs of my arms. I cannot stop them. I would not stop them.

Love is a great beautifier.

One daughter is ferociously following her career, stalking it like a hunter. Because she can read tracks of possibility and smell opportunity on the wind, she finds the hidden work that can feed her soul. She has a quiet center to hold herself firm out in the wild. She went to the Women’s March in Washington – on her own. At 23. From Boston.

And one is a mother, one child running full-tilt into each day, one swimming in the deep waters within her, soon to arrive. She speaks many languages – English, Spanish, and also Compassion, Poverty, Art, Confidence, Encouragement, Strength. A woman of the high desert, she communicates with rock and stone, tender green and yellow flower, warm fire and stars at night. With all people. But the new baby is too close, and the 2-year-old too fast and fearless, for her to come to the March in Denver.

Far away there in the sunshine are my highest aspirations. I may not reach them, but I can look up and see their beauty, believe in them, and try to follow where they lead.

They are my sun and moon, these two women of my heart, guiding me by day and night. And everything they represent is in danger.

Painful as it may be, a significant emotional event can be the catalyst for choosing a direction that serves us – and those around us – more effectively. Look for the learning.

So I met my sister at Union Station, a fitting name. And we and her friend joined 100,000 new friends at Civic Center Park, another fitting name, and wrote our dreams like nametags on scraps of paper we tied together into prayer flags for us all – old, young, queer, straight, trans, sis, black brown red white yellow purple green, a pink-hatted rainbow of human beings with the sharp ears of cats, hopes fluttering and dancing and stomping their feet to warm their toes on a chilly Saturday morning along the Rockies.

I heard a woman say to the teens walking by with her, “You’re making history.”

And that is when I really saw them – the little women. Girls, everywhere, such thin little arms and legs, long forming faces and chubby cheeks, signs in their hands, signs hung by their legs, signs in front and behind them. I wanted to read their words, hear their words. So I just started asking.

“Hi, can I see your sign? What do you think of all this?”

“Really cool – that people are standing up for our country.”

“What would you tell President Trump if you could?”

“I don’t know….”

“What’s on your sign?”

“Respect.”

“Would you tell him that? Who should he respect?”

“Us. Everybody. Women.” — Talulah, 11

And so I sought them out. So many little women, apprehensive or bold, verbose or shy. Holding signs of power and dignity.

“I’m here cuz Trump sucks. I would tell him, ‘You suck – be nice to people.'” — Carmen, 9

“The things you say aren’t right. You should be more fair.” — Amelia, 9

“I’m here to fight for our rights. I don’t think he’s a very good president. I would tell him, ‘Respect people’s rights and keep the Affordable Care Act and other things people depend on.'” — Lucia, 12 “Respect people’s health care.” — Maggie, 10

“‘Treat people the way you would want to be treated’ – does he? Not everyone.” — Sofia, 11 “I’m here to protest for our rights – our ability to have our voice heard. I would say, ‘Everyone should be equal. Treat everyone the same.'” — Clara, 11

“He should treat everybody the same.” — Mia, 9

And then, just before we finally marched, something opened up. The boys started talking to me.

A sweet boy emerged from among the girls. “I’m here to march with my mother. I think some things are gonna change. I don’t really know which, but I know something’s gonna change.” — Wilder, 11

A tall, skinny teen laughed and smiled with his little sister, who was on their father’s shoulders. I pointed to him and said, “We’re glad you’re here.” Women behind me repeated the sentiment. He beamed and said, “I wanted to be here.”

Two young, beautiful men, a mixed-race gay couple, held hands as they marched. “We didn’t bring a sign, so this is our sign,” one said, lifting their joined hands. I asked if they were able to do this all the time, any time they wanted. “Well I would, but not him.” They laughed. “It’s getting better. Obviously, here, we can. You pay attention, sometimes you can, sometimes no. But it’s getting better.”

Let my name stand among those who are willing to bear ridicule and reproach for the truth’s sake, and so earn some right to rejoice when the victory is won.

I learned so much yesterday – about my sister’s love of community, about my daughters’ security in themselves, about other mothers’ daughters and their beliefs in respect and inclusivity. And about other mothers’ sons – men, like my own sons, who offer respect as a matter of course. Who believe firmly that things can change, that things get better.

I learned about the power of protest, when we walk together to have “our voice heard” – our voice, like 11-year-old Clara said. Loud, chanting, repeating the words that matter. Many people, one voice. Taking one step together, then another.

Mia, 9

Thank you to the parents/guardians of these young people for giving permission at the march for photos and interviews. Any proceeds from this article are being donated to N.O.W. (National Organization for Women).

January 22, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Finally, across the river it appears, languid as a waking cat, a gray panther rippling and slowly rising, turning its head my way. Through the train window, I see New York for the first time.

The music of the train on the tracks beats the rhythm of the city.

I’ve been to every single book I know

to soothe the thoughts that plague me so

stop before you start

be still my beating heart

(be – still – my – beat – ing – heart)

— Sting, Be Still My Beating Heart

I have the giddy excitement of the young artist wrapped in the aging body of the immigrant family patriarch. I think about how my family first came to New York by boat from the icy waters of Sweden and Denmark. My 12-year-old great-grandmother bringing her young girl heart and sweet possessions in a curving trunk with little blue flowers embossed and painted on the tin between arcing wooden ribs. My grandmother born first generation in this country.

I remember a great-great-grandfather who sailed between Denmark and the U.S. multiple times, checking on his sons in America, darning their socks I am told in childhood stories, and cooking with them, these young green men eating the traditional food of their father and his homeland.

My people leave. We go. The descendants of Vikings, we sense a larger world, and make epic voyages to find places of a scale to match our vision. Or so we tell ourselves. We feel confined, is the root cause. Constricted, by small minds and limited opportunities and a blood sense that there is more to us than we have yet seen in ourselves. We chain ourselves with responsibilities, then chafe raw against the shackles. We create home, then leave it behind.

You tell him to come in sit down

but something makes you turn around

The door is open you can’t close your shelter

You try the handle of the road

It opens do not be afraid

It’s you my love, you who are the stranger

It’s you my love, you who are the stranger.

— Leonard Cohen, The Stranger Song

It’s not particularly noble. But it is fierce, and within each generation, we seem to have one who feels it like a burning in the skin, some fire that can only be quenched by returning to the sea, to windswept ice and snow, to mountain peaks – to wild and endless vistas. My grandpa Holger left his farm and young family to see the wide Pacific, breathing with the endless tides. My father left the midwest farm over and over, for the cowboy dream of the West, for the oceans, for the mountains, for a traveler’s life across America.

Where do I put this fire

this bright red feeling

this tiger lily down my throat

it wants to grow to 20 feet tall

I’ve left bethlehem

I feel free

I’ve left the girl I was supposed to be and

someday I’ll be born

— Paula Cole, Tiger

I want to leave America itself – so first, I am returning to the gateway. Where languages swirl from the streets through books I have read and never read and poems yet to be written. New York: oh holy Mecca of poets. To find myself at home among my patron saints, living and gone. So I can go.

We create the gods we kill

then give them

immortality…

— Sting, 50,000

I cannot write one essay that captures my week in New York. I will be sending postcards from New York for the rest of my life, 4×6 illuminated manuscripts of ordinary street life written in holy water from the filthy Hudson and East rivers. As a pilgrim on this spiral poet’s path, walking through Central Park and over the Brooklyn Bridge and down into the subway stations was every bit as sacred as entering a zendo or a cathedral or circling the kaaba, the huge dark squares of this city containing the alien, meteoric soul of word and rhythm and sound, survived from beyond familiar life and atmosphere to arrive burning with the message of endless worlds and endless possibilities.

Step outside

take a step outside …

heart’s on fire

leave it all behind you …

dark as night

let the lightning guide you …

— Jose Gonzalez, Step Out

It has birthed a tiny book, chapbook preemie still in the supportive incubator of layout and typeface, its photos taped like oxygen tubes into its tiny nostrils, reaching and softly kicking the smallest arms and legs of lyric and image. It is growing into it’s strongest self, now, under caring attendance. It is warm, and alive. Like a new generation in this land of immigrants. Like a newly-discovered holy scroll written on crumbling newspaper unearthed beneath a torn-up subway track. I will take it with me; and ultimately, I will stand it on it’s own strength, and I will leave it behind.