December 8, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

if you do not stop

to give the penny

what blessing

are you missing

If I hadn’t taken the river walk through one town, instead of the main street route, I would have missed the artist drawing a river scene. I asked if I could stand near him and see. His pencil scratched delicate and lovely lines onto thick paper in the man’s sketch pad spread open across his lap. He slowly added shadow into the trees on the hill, and underneath the bridge arches.

Darkness is the illustration of depth. We must add contrast to give dimension; deep shadow allows the surfaces touched by light to rise, come forward. All this the artist did, effortlessly.

The river walk was a boardwalk along several stretches, paved sidewalk along others. The boardwalk stayed damp and slippery, however, so some ingenious worker had added a mat of chicken wire over the boards, creating traction. The design was fascinating, and I could see old rust marks from earlier layers of wire mesh now worn away.

The pressure of touch is a contrast of forces, and can easily slip away, or leave a mark, if the forces are out of balance. Sometimes, both. All this I knew, only too well. Effortlessly, now.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

By eleven in the morning, my day had already been intense, moving and transcendent.

At 4am, the older man in our room at the Oviedo albergue had a stroke or heart attack, slowly falling from his bunk in total darkness, unresponsive to his partner as she called his name over and over into the unrelenting black. Michael. Michael.

We snapped on the cruel overhead light, and found him curled up, slumped on the floor. His partner called for emergency assistance. The albergue staff were all gone for the night. I told her no food or water, and went to open the locked gates for the ambulance crew. I assured them the partner spoke Spanish as I led the way up endless narrow stairs.

The albergue appeared to be part of an old prison or an old monastery, a wedded complex of multiple buildings. Earlier in the evening, the church next door was filled with singing, in Latin and Spanish, hymns and simple folk tunes of faith wafting from their open windows, lulling me to sleep beneath mine.

Now Michael was on his way to the hospital. The girl from Mexico had been badly scared by the whole event, so we talked a bit afterward. I reassured her that he was in the best hands now, and her shaky breathing eased, so that we lay down and slept again until 8am. At 9am, readying to leave, we found out he was out of the hospital, as his tests had all come back fine. He was deemed okay for discharge, according to his partner, even though neither the girl from Mexico nor I thought he was really okay. His partner had told the girl that Michael wanted to continue walking. The girl was upset at this idea; however, we finally settled on a truth we could both immediately acknowledge: each person chooses his own Camino.

I had planned to crash the Sunday morning mass at the Catedral de San Salvador, the Oviedo Cathedral Basilica on the central plaza, just for the experience. Now I felt like I needed it. I figured my pilgrim’s backpack and walking stick ought to get me in, plus “no hablo Español.” It wasn’t like Catholics were card-carrying or had a secret handshake at the speakeasy door; surely a showered peregrina could attend.

I had planned to crash the Sunday morning mass at the Catedral de San Salvador, the Oviedo Cathedral Basilica on the central plaza, just for the experience. Now I felt like I needed it. I figured my pilgrim’s backpack and walking stick ought to get me in, plus “no hablo Español.” It wasn’t like Catholics were card-carrying or had a secret handshake at the speakeasy door; surely a showered peregrina could attend.

Just before 10am, I entered the main doors. Leaving everything I owned behind, my backpack tucked in a shadowy corner of the narthex, and leaning Saint Thomas beside it for protection, I stepped forward into the cathedral itself to see the main altar.

Designed to illustrate the Bible for non-readers of the early 1500’s, it was gilded, floor to ceiling, filled with outlined biblical scenes in a three-dimensional quilt of painted relief sculptures.

For me, after a long night watching Life and Death haggle over the price of a man, it shone. Not the illustrated Christian stories themselves, or the Bible per se, and certainly not the Catholic Church’s long and terrible history of conquest and oppression. The altar was simply about some human being, some man, alive centuries ago, making a creation of beauty with his warm, living hands.

For me, after a long night watching Life and Death haggle over the price of a man, it shone. Not the illustrated Christian stories themselves, or the Bible per se, and certainly not the Catholic Church’s long and terrible history of conquest and oppression. The altar was simply about some human being, some man, alive centuries ago, making a creation of beauty with his warm, living hands.

The Virgen de Covadonga, patron saint of Asturias, stood serene, front and center in her turquoise and white, as all of humanity’s struggles, triumphs, and agonies played out behind her turned back. Michael shakily stepping off again on the Camino, the girl from Mexico breaking in her new boots as she started her journey, me heading inland, inward, into the oldest heart of the Camino.

San Salvador means “Holy Savior.” One definition of a savior is someone who salvages what they can. I thought of a beachcomber after a shipwreck, pulling cargo and gear, survivors and the unlucky, ashore. Sometimes, it’s hard to tell which is which. You’re too busy saving what you can to sort it out in the moment.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I learned a useful distinction in my 20’s, and had been repurposing it for decades ever since. Sometimes, in the still quiet of utter darkness, you hear something, a song, words, your own unassailable voice from the center of your heart. When you hear it, you must listen. These will be words to live by.

Back then, sitting at my dining table, hands flat in front of me, feet flat on the floor, back tall and square in my chair, I held myself in a posture of alignment with Fate, the copious handful of pills I had swallowed already beginning to take effect by producing the most solid calm I have ever experienced.

And that was when my own mind spoke to me: I don’t want my life to end. I want THIS life to end.

In those dark days, I had believed lies, lies upon lies, that I was damaged, defective, ruined. A beautiful wreck that could not be salvaged, slowly sinking into oblivion beyond the shore. But the truth was light, rising above the storm, here in the mind’s eye. Deep shadow allows the surfaces touched by light to rise, come forward.

Eye of the storm; eye of wisdom.

When you know you have heard the truth, decision-making becomes easy. Slurring into the phone, I calmly called for help. And lying in the emergency room, swallowing a tube to pump my stomach, I felt fine, listening to my own breathing, in and out, around the plastic lifeline that saved me from lies.

Recovering in the intensive care unit, I felt bad only because I knew I did not need to be there. The hospital’s young psychiatrist was sweating nervously when he met with me, but I reassured him that I was feeling better and would follow up on his counseling recommendations; relieved, he left quickly.

The older hospital chaplain and I had quite a longer talk. I hadn’t converted or found God or seen a beachside apparition of the Virgin Mary (yet). I was just a Buddhist who hadn’t believed the core tenant of Buddhism, because I hadn’t really experienced it: basic goodness. That Life is, at its essence, a constant energy for good. The chaplain and I agreed, too: shit happens. Doesn’t mean that Life Itself isn’t good. Contrast gives dimension, sometimes beautifully, sometimes shockingly, sometimes tragically: it’s a matter of where you choose to focus your gaze, what you allow to rise.

It’s not about ignoring; it’s about how we decide to spend the time we get. Stripped of all our assets, skills, talents, then focus is ultimately all we have; caring attention is what we can give.

“How did you come to this place, this frame of mind, today?” he asked me.

“I woke up. And looking out that window, I know it sounds, trite…cliche…but I was…amazed, at the blue, blue sky. Amazed. It was so blue. And I thought: this day would have happened, with or without me. I would have missed it, this morning I want to remember forever. And that’s when I realized that I’d never made a commitment to be here. You know? I was always kind of one foot in, one foot out, hating my life. So I decided. I’m going to be here, no matter what. I’m going to live, every single day, until I die.”

He looked at me funny, probably trying to see if I was serious, or lying, or trying to appease him, or just weird. “Barbara,” he said, finally, “you’re gonna be all right.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Holy Savior’s Cathedral in Oviedo was a collection of tiny chapels added one by one onto each other, holding together, growing in faith as it became a great basilica. The original starting point of the original Camino dating from the late 700s-early 800s, it became a required detour in the Middle Ages for pilgrims. It was said,

“Who goes to Santiago, but not to Salvador,

visits the servant but not the Lord.”

For me, the Lord was Life. And Life had many servants – Joy. Compassion. Love. As I thought about Michael’s fall in the night at the albergue, I felt the sobering weight of the reality that our lives end. They do. I remembered all the homeless people I had met over my years of work, hopeless and defeated, considering the very choices I had made, to keep that formal date with Fate, to slip away, to fall in the darkness and not return.

And then I remembered all of those people I had sat with, one by one in my office, hoping to give time and attention to their stories, wanting to hear them out. When I was patient, and lucky, they sometimes gave me the gift of their trust, letting me have a peek into their lives.

I had been given a gift as well, to share in exchange with them: those words. After all the story had been told and I thanked them for telling it, after men grown battle-hardened and street-weary had cried into their dirt-lined hands, when the space between us had once again become still, quiet, I would finally ask, “So…do you really want your life to end? Or do you want THIS life to end? Which do you think it is?”

Words to live by. For me, and now for countless homeless men and women. I felt so lucky, to have a low-down, gritty commonality that mattered in that moment. I felt grateful to the pills, and to the stomach pump. I never told my story; I just passed along the words that had kept me living.

And they kept living. Many decided to change their focus. Many changed their lives.

They certainly changed mine. They touched me, deeply. I understood what they were saying, and in turn, I finally connected, with other human beings. A child without a safe home is a homeless child, whether they still live in that house, or not. You can carry that house with you for a long time, still homeless.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

While I stood before the great altar, I noticed people ducking into one of the side chapels. Another couple. An older man. Tourists, locals. Intrigued, I followed.

It was the 10am mass, in a smaller, more intimate chapel that was still breathtakingly beautiful. Old stone arches rose above us in our humble wooden pews, windows high above streaming filtered morning sunlight down upon us. The service was in Spanish.

It was the 10am mass, in a smaller, more intimate chapel that was still breathtakingly beautiful. Old stone arches rose above us in our humble wooden pews, windows high above streaming filtered morning sunlight down upon us. The service was in Spanish.

I understood snippets of the words of the Lord’s Prayer, our pan de dia, and thought of peregrinos along the Camino breaking baguettes of bread to share with one another.

We stood and offered each other peace, shaking hands across bench backs and aisles, turning to shake hands behind me as well. Communion was offered, and I thought this might be the best time to leave, slip away. But watching a line of the faithful slowly moving forward up the center aisle, I heard a voice.

Somewhere behind me, a woman began singing. An operatic voice, clear, sweet, gorgeous. I turned ever so slightly to look, and saw that it was the young woman I had just shaken hands with, smiled with, offering each other peace.

Now, she gave us this gift. She sang two songs, one I did not recognize, but one I did. “Ave Maria.” Hail Mary. Crying Out to The Great Mother of Mercy. She Who Hears The Cries of The World.

I just sat, transfixed, like everyone else who did not go forward. I would have missed an experience I wanted to remember forever. A voice that brought tears to my eyes, and did again as I was writing in my notebook over coffee, reliving the moment. Life affirming, transcendent. This feeling of the sacred worth, the basic goodness of Life – this was why people created religions, and why others created art.

And why some sit in small offices, talking to homeless people about the meaning of life. It’s all a Hail Mary, this existence…a beautiful, holy salvage job.

Hail Mary, Full of Grace

God is with thee

Blessed art thou amongst women

And blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus

Holy Mary, Holy Mary

Pray for us sinners

Now and in

The hour of our death

Ave Maria

December 6, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

moving in silent desperation

keeping an eye on the Holy Land

a hypothetical destination

say, who is this walking man?

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

Walking Man passed me again, suddenly strolling by out of nowhere with his long legs, easy stride, browned chest, and pale blue turban to keep what I suspected was a bald head covered from the sun. Long and lean, his sinewy arms and legs were built for trekking. Walking Man never said a word except “Hello,” each time he passed, or I passed him as he sat drinking coffee at a cafe, or he passed me again within an hour.

A Northern European by appearance, he carried an altogether different air than any of the peregrinos I had met. So when I came upon him sitting on a rock in a shady patch of trail, I said “Hello” – and this time, I stopped. Walking Man was taking a break, and offered me pistachios.

His name was Jan. He was Dutch, but told me he lived in the Caribbean, where he grew up. At age 4, his parents put him in a baby seat and biked all over Europe with him. So he had truly been traveling the world his entire life. I looked forward to talking more, hearing how all this travel had shaped his life, who he had become now. But the day was heating up, so I left him in the shade, confident he would pass me again later.

The heat was stifling, the humid air crackling like electricity on my upper lip and burning at my nostrils. Inspired by Jan, I wrapped my long cotton scarf over my head, not like a turban, but like a hood. Feeling very Lawrence of Arabia as I pulled it forward to shade my forehead, I continued on. It was so much cooler, I smiled. Air flowed under my scarf and around my head like a shimmering mirage of an oasis ahead, and my neck and shoulders instantly relaxed. The afternoon heat continued, relentlessly.

well the leaves have come to turning

and the goose has gone to fly

and bridges are for burning

so don’t you let that yearning pass you by

walking man

walking man walks

any other man stops and talks

but the walking man walks

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

Around 2:30pm, I walked past the fenced courtyard of a home. Within, a large family was gathered for lunch at outdoor tables under tall trees. I was hailed to come in by the gate. As the mother opened it, she asked, “Agua? Agua?” and so, giving her my water bottles, she filled them with water – and ice.

Meanwhile, I was invited to the tables with aunts and uncles, cousins and siblings, where the father offered, “Sidra?” And so, turning himself nearly horizontal, he poured the regional apple cider from as high as his hand could reach, down into a cider glass in his lower hand, a waterfall of crisp, delicious bubbles. I sat and asked how old the chubby, dark-haired babies were, tickling them under their fat chins until they giggled, drank my sidra, and, completely refreshed, bid them all muchas gracias and adios as they called buen camino and buen viaje.

well the frost is on the pumpkin

and the hay is in the barn

pappy’s come to rambling on

stumbling around drunk down on the farm

and the walking man walks

doesn’t know nothing at all

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

Soon after, Jan caught up to me. I told him how the family had invited me in for cider, had given me ice water. He smiled indulgently, and I felt like the novice I was, just getting my feet wet in the wide world. “Buen Camino,” he said kindly, and strode away. I never saw him again.

any other man stops and talks

but the walking man walks on by

walk on by

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

Before Pola, two white-haired grannies walking together on the road let me take their photo. They scolded me that Oviedo was too far to walk in this heat, and I should stop in Pola. But Pola was a rundown, depressing industrial town, and not a soul smiled as I walked through. I pushed on.

most everybody got seed to sow

it ain’t always easy for a weed to grow, oh no

so he don’t hoe the row for no one

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

By 5pm, I reached Oviedo. It had its rundown areas, too, some so sketchy I was glad it was still daylight as I was walking through. Up, up, up a hill, arriba alto, to the catedral, the locals told me. My legs slowly climbed the paved sidewalks, still radiating heat. My water was nearly gone; I drank twice my normal two liters to make my hike under the intense Asturian sun.

At a busy intersection, I stopped for a traffic light, looking for Camino arrows or scallop shells to point me toward the albergue. Three peregrinos stood beside me, talking in accented English about the same thing. I asked if they knew where it was, and they said yes, I could follow them.

We walked up narrow, steep streets into the old city, and around a corner, I found myself on the plaza in front of the cathedral. Their photo op accomplished, one young man said he would show me the way. As we climbed more streets, we both became somewhat confused as to where we were. We stopped at a bar and he asked the barman for directions.

“Just down that street, you can’t miss it,” the man said in English, pointing slightly downhill. We thanked him and set off again. Within a minute, we knew we had been given Spanish Directions: it is apparently socially awkward to be caught unable to direct someone to where they need to go, so Spaniards have a tendency to bluff, giving very clear but completely wrong directions. We turned around.

“Don’t believe when you’re told the next stop is 2 km, either,” I told the young man. “It’s miraculously, always, exactly 2 km.” We laughed as we huffed up another steep street.

for sure he’s always missing

and something ain’t never quite right

ah but who would want to listen to him

kissin’ his existence good night

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

By the time we recognized the street names near the albergue, my legs were exhausted from the long day’s extreme heat and hills. The young man offered me his walking stick, as well, when I struggled to climb a long series of steps to our destination. Grateful, I thanked him and accepted. That was smart; I immediately found my feet again, and we located the gate to the albergue within minutes.

I gave him back his stick, and he wished me “Buen Camino,” turning to leave.

“Aren’t you coming in?” I asked.

“No, we have a hotel room,” he smiled.

“Oh no, I’m so sorry! I thought you were trying to find the albergue, too,” I apologized.

“Buen Camino, peregrina,” he smiled again. And away he went, disappearing down the hills.

walking man

walk on by my door

any other man stops and talks

but not the walking man

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

As I checked in at the albergue, I was given a second credencial for sellos, as my first one was full. An Oviedo stamp ended my first booklet, and another started my second. I looked back at all the places I had already been, stamps with shells and crosses, images of saints and pilgrims interchangeable across the folds.

The Norte was now officially done. I thought of all the people I probably would never see again, people I had met and walked with, talked for hours and laughed with, made decisions with, eaten with, slept side by side. Some had already passed on ahead of me, some had gone home; many would continue on the Norte to the end.

We were all just walking allegories of our lives, each finding our way. I was learning to stop and meet people, in gratitude and in wonder; yet I wished I had asked them more, about their lives, about their ideas about life in general. Too soon, they walked away, without my realizing the crossing of our paths was over.

I was hoping one day to be a white-haired granny walking arm-in-arm with a friend, indulgently scolding younger people for their hurry through these, our only days.

Or I might just say, “Buen Camino, peregrina.” Each her own Camino, wherever she may be bound.

he’s the walking man, born to walk

walk on, walking man

well now, would he have wings to fly

would he be free?

golden wings against the sky, walking man

walk on by

so long, walking man

— James Taylor, “Walking Man”

December 5, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Gorma woke up very gently, the morning she arose in the loveliest albergue on the Camino. The sun was just starting to awaken, and so, too, the chickens in the yard, and the birds in the trees. The dogs stretched, one by one, each standing and stretching its legs, one by one, until all the legs were awake as well, and then they all trotted off down the lane, dog by dog by dog.

By the time the rooster crowed his good morning to the farmyard, Gorma was sipping her coffee in the warm farmhouse kitchen. For you see, this albergue was simply beds for weary travelers offered by a hardworking family – right in their own home! When Gorma had commented on this amazing situation the evening before, while the travelers ate supper grown from the garden and cooked by the family, the mother Marisa would say, “It is only a simple house, nothing more.” But it was something more, as Gorma well knew, for her sleep was as deep as this rich morning coffee, she woke as refreshed as the warm, soothing shower, and was delighted by the delicious cake for breakfast, baked fresh in the earliest hours of the day, well before dawn, sprinkled with the sweetness of children’s dreams.

The father of the house, Gaizka, joined Gorma for coffee and reminded her, “Now, Gorma, Gorma, do not forget all we talked about last night at supper. For we here in the North of the Country of the Heart, we are the keepers of the Freedom of the Heart, and the Freedom of the Heart is Honor, as you know. Do not forget to see the Tree of Honor, which for us is the Tree of Life, and so the Tree of Everything. For at the Tree of Honor, our fathers’ fathers and mothers’ mothers swore to keep the heart of this country free, always, and always we will do so. It is our most important symbol, this tree. You will find it surrounded by a glimmering circle of silver, and blanketed in velvet green, like the noble of our land that it is. Before you leave these high hills, you must see it, Gorma.”

“I will see the tree, Gaizka,” Gorma replied seriously, “for I already know the power it has over the people and this land. It is the magic I have sensed ever since I arrived in your beautiful farmhouse.”

“This is only a simple house, Gorma, nothing more,” Gaizka said, raising his arms and spreading his hands like a great tree, to show the utmost honesty, no magic tricks then being played.

“Oh no, it is much more, and has the Tree of Honor to thank for it. But I must be on my way.”

So Gorma shook hands with Gaizka and hugged Marisa and walked down the dirt road with Saint Thomas, her walking stick. She saw many, many trees, hillsides of trees sometimes, but none encircled by glimmering silver and blanketed in the velvet green of a noble.

Soon, the day became hot, so Gorma stopped by the side of the road, sitting in a shady patch of grass. She ate her bread and cheese, then looked in her bag one more time. “No fruit,” she said aloud, and reached for her water jug.

“Well, Gorma, would you like an apple or a pear?” asked a voice quite close behind her. Gorma turned, and saw that the shady patch was due to a most beautiful old tree. Two smaller trunks had twisted round each other many years ago, when they were young, and now this tree curved gracefully, with full and arcing branches. Gorma saw that on one side of the tree grew apples, and on the other side grew pears. A blanket of velvety moss grew up and into the entwined trunks, and a clear stream circled the tree before flowing down the hills, flashing silver in the midday sun.

“Are you the Tree of Everything?” Gorma asked, realizing who had spoken to her.

“Well, I don’t know about everything, but we have apples, and pears. So we have more than most.” The apple half was Antoine, and the pear half was Pauline, planted side by side quite by chance many years ago. And then, growing quickly as all young things do, and chasing the sun through the course of each day, they’d ended up twirled round each other in this wondrously woven way, once two, now one.

“What does a Tree of Everything look like?” asked Antoine curiously.

So Gorma told them, “It is old, and strong, surrounded by a glimmering circle of silver, and blanketed in velvet green, like a noble of this land.”

Pauline and Antoine laughed and laughed. “Oh, Gorma, Gorma, we have only this little stream, and a blanket of moss. But we have been standing here as long as the little village down the road. So I guess we are a bit old, and a bit strong at that, if only stubbornly so,” Antoine replied, smiling.

“Tell us, Gorma, what does a Tree of Everything do?” asked Pauline, for she was most productive with her pears.

So Gorma told them, “The Tree of Everything is the Tree of Honor, where the fathers’ fathers and the mothers’ mothers swore to keep the Heart free, always, and always will do so.”

Pauline and Antoine laughed and laughed again. “Oh, Gorma, Gorma, we are just a village tree. Although, one time, a village boy fell in love with a village girl, standing right where you are now. He knew she brought her family’s cows here to drink from our stream, and nibble fallen pears and fallen apples, so he began to leave her love notes, here – just here,” replied Pauline, and showed a space between their two trunks that was still open and apart, like a pocket.

“And then what happened?” Gorma asked, snacking on the apple Antoine handed her.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, it was just so beautiful,” Antoine sighed, and Pauline nodded. “Here they made vows, with the village gathered round, and the birds all sang, flowers blooming everywhere….”

“They pledged their love, Gorma, here, just here,” added Pauline, and showed a space of smooth, clean stone beneath the moss. “I hear that they have children now, a family, but their house is a distance yet from here.”

“Ah, just so beautiful it was, Gorma, the wedding of sweet Marisa and young Gaizka,” and Antoine sighed dreamily again.

Then Gorma smiled, and hugged the tree, and all three laughed together in joy as Gorma told them of Marisa’s house, and of all Gaizka had said, and how the children tend the chickens and chase the dogs. For the magic of the “simple house and nothing more” was that it was a home, a real home, bound by honor, which is the solid stone beneath all love.

Pauline agreed. “And honor in a home allows a space for two to live as one, and still be two -”

“- like me and you,” added Antoine to his Pauline.

“Like me and you,” agreed Pauline with her Antoine.

“So to this village, and that family, you have become the Tree of Everything, for you have heard the vows, and held the honor of the freedom of the heart within you, in openness and joy. Thank you for shade, and for apples, and pears, and for laughter, and for sweet places for love notes and stories,” added Gorma, as she packed her bag to travel on. Then Pauline gave her a perfect pear, which she took along with a fresh jug of water from the stream, and waved goodbye.

Gorma walked on, quiet and smiling, munching on her pear. She arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. Outside, the trees sighed happily in the soft breezes of the night, and somewhere tucked away among the high hills, the great Tree of Everything watched over all.

Buen Camino, Antoine and Pauline.

December 5, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I turn my new

washed socks

and sand

sprinkles the air

like snowflakes

remember

remember the sea

Apparently so intent to hike over the highest mountains, I took the high road I had planned to skip. The Primitivo was showing itself to be a path of choices already made.

I wasn’t technically lost; my route over the third high hill I did not intend to hike was, in fact, a route on the Camino…an alternate route. I had just intended to be a slacker, but missed my slacker exit. So I got lost by staying on track, and took the Alto de la Campa – the high scenic route. The very high scenic route, off the main roadways; the good kind of missed exit, you realize later, after the point of no return is far behind you.

A road biker in spandex called out, “Buen Camino!”, giving me a panting thumbs-up as he passed me on the other side of the tough, steep road, both of us loaded down and climbing on. Taking the turn to Arbazal, my road became even steeper. The guidebook had said that once I reached the village, the route would flatten out and become easier. One thing was instantly clear: Smart Alex had never walked the route through Arbazal. Using only my toes to ascend the road like I was rock scrambling on the approach to a summit, I reached the top of nowhere. Green mountains stretched before me in all directions.

Walking up such precipitous roads is actually the easy part, though you’re a sweaty mess and your pack feels like a freight train going the opposite direction. It’s the downhills that will get you. It’s the choices you made earlier that tell, now.

I had walked with a slightly unbalanced pack, not wanting to halt my momentum to stop and readjust, and so now my left shin was hurting, especially when absorbing the impact of the downhills, and I had a long, steep downhill before me. Several, in fact. Kilometers of downhill.

I had walked with a slightly unbalanced pack, not wanting to halt my momentum to stop and readjust, and so now my left shin was hurting, especially when absorbing the impact of the downhills, and I had a long, steep downhill before me. Several, in fact. Kilometers of downhill.

As I looked down the road, I was concerned, as a shin splint could lead to a stress fracture and could end my camino. Seventeen-year-old me winced at the thought, remembering stress fractures causing calcium deposits like goose eggs on both shins during my short-lived high school basketball days.

As I looked down the road, I was concerned, as a shin splint could lead to a stress fracture and could end my camino. Seventeen-year-old me winced at the thought, remembering stress fractures causing calcium deposits like goose eggs on both shins during my short-lived high school basketball days.

But then, she heard something.

A rhythmic music pulsed in my mind. Bomp-bomp-bomp, BAH-dah, bomp-bomp-bomp, BAH-dah, bomp-bomp-bomp, BAH-dah, bomp-bomp-bomp, BAH-dah – what the heck? “La La Land”?

The charming grin of my youngest, teenage son, Magnus (Max for short), appeared in my mind as if beside me, head bobbing as he sang along, laughingly taunting and encouraging me. A high school jazz musician, Max had loved the sweetness of the movie, “La La Land,” and, in his own lanky sweetness, often grabbed me for an impromptu dance step as we walked together anywhere, into the grocery store, dropping off a book at the library, walking through the park. Now, here he was again, offering his hand.

I grinned back. Picking up Saint Thomas in both hands, I envisioned Max and I wearing top hat and tails, dancing with canes. This was it – our big musical number. With a nod, and one of Svend’s winks, I began singing along to the cadence, “bomp-bomp-bomp, BAH-dah,” and started dancing down the hill, first to the left, then right, then left again, angling jauntily down the steep inclines, laughing with Max. Feeling no pain. Not the coach’s “no pain, no gain” of my own teenage experience – NO pain. Just fun. Only a delighted, exhausted joyfulness.

I grinned back. Picking up Saint Thomas in both hands, I envisioned Max and I wearing top hat and tails, dancing with canes. This was it – our big musical number. With a nod, and one of Svend’s winks, I began singing along to the cadence, “bomp-bomp-bomp, BAH-dah,” and started dancing down the hill, first to the left, then right, then left again, angling jauntily down the steep inclines, laughing with Max. Feeling no pain. Not the coach’s “no pain, no gain” of my own teenage experience – NO pain. Just fun. Only a delighted, exhausted joyfulness.

I understood that my three treks astray on the Camino represented something significant. I decided they were more Camino magic, three hikes to let me learn one lesson, about: Marriage. Dancing and singing down those kilometers, I knew I had tried to walk paths that were not my Way, that were defined for me by limitation and the expectations of others, trying to fit in, to prove something to other people.

I had tried to prove that, despite my rocky early years, I was fine – the ultimate fine, I was girl-next-door-ordinary, some definition of normalcy that safely but firmly defied my early branding of “gifted” and “brilliant” and “extraordinary,” and numbingly belied the obvious signs of artistic and spiritual seeking and a call to walk a little wild and a little stupid at times. And because, deep down, I didn’t actually, truly believe that I was fine the way I was, I had chosen marriage as a sign of social acceptability, a golden band of respectability. I had done this three times. And three times, I had completely lost myself, until I decided to leave that path and get back on track. To me. To walking my own Way. To thine own weird, wonderful self be true.

Yet my scrambles, over bewildering hills I did not mean to climb, had led me to my children. And these were people to whom I most definitely had nothing to prove. They had seen me in some of my most idiotic moments, and still loved and respected me. I liked to think that, because I took the time to explain my miscalculations to them, they felt a generosity toward their wildly improvising parent, while also learning that it was okay to make mistakes. But maybe they were just kinder than me. Or smarter. Or just healthier. They were people who seemed to take the high road naturally.

Yet my scrambles, over bewildering hills I did not mean to climb, had led me to my children. And these were people to whom I most definitely had nothing to prove. They had seen me in some of my most idiotic moments, and still loved and respected me. I liked to think that, because I took the time to explain my miscalculations to them, they felt a generosity toward their wildly improvising parent, while also learning that it was okay to make mistakes. But maybe they were just kinder than me. Or smarter. Or just healthier. They were people who seemed to take the high road naturally.

Only Max knew how to dance down the hills in joy, however. He knew already that, despite how much he might want to fit in, to respectable society, to new schools and new peer groups, no matter how hard he tried, he could not control Life. So he did his best, seeking structure and proven, clearly marked trails, measuring himself and his progress toward his goals; yet, surprisingly true to himself, he also allowed his love of improvisation, feeling his way. And a little child shall lead them, by bebop, funk, or the blues, sometimes playing his heart out, sometimes marching to his own cadenced drummer, one we could not always hear.

After that, if my legs even began to twinge, I did a little song-and-dance number, which shifted my weight and the pressures on my bones and tendons, easing the strain. I pushed myself up the hills, feeling strong, the way I loved to hike, but now, looking down from the tops of green mountains over a sea of flowers, I remembered how I had played on the beaches. My legs never gave me any more trouble, though I still had over 500 km to go to reach Santiago, Muxia and Finisterre.

But first, I had many high roads to take, over many, many hills. Time to follow the butterflies, over fences of my own making.

Improvisation is the ability to create something very spiritual, something of one’s own….It’s all about creation and surprise. It just needs to be appreciated and watered like flowers. You have to water flowers. These peaks will come again.

— Sonny Rollins, jazz sax legend

December 5, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I like this farmer

tall and thin

like my own

grandfather

he has stopped

to tend his cows

my grandfather

had cows

before

I existed

cows in

our family

with names

and bells

for him to find

them I will

hang bells

for him

to find

me

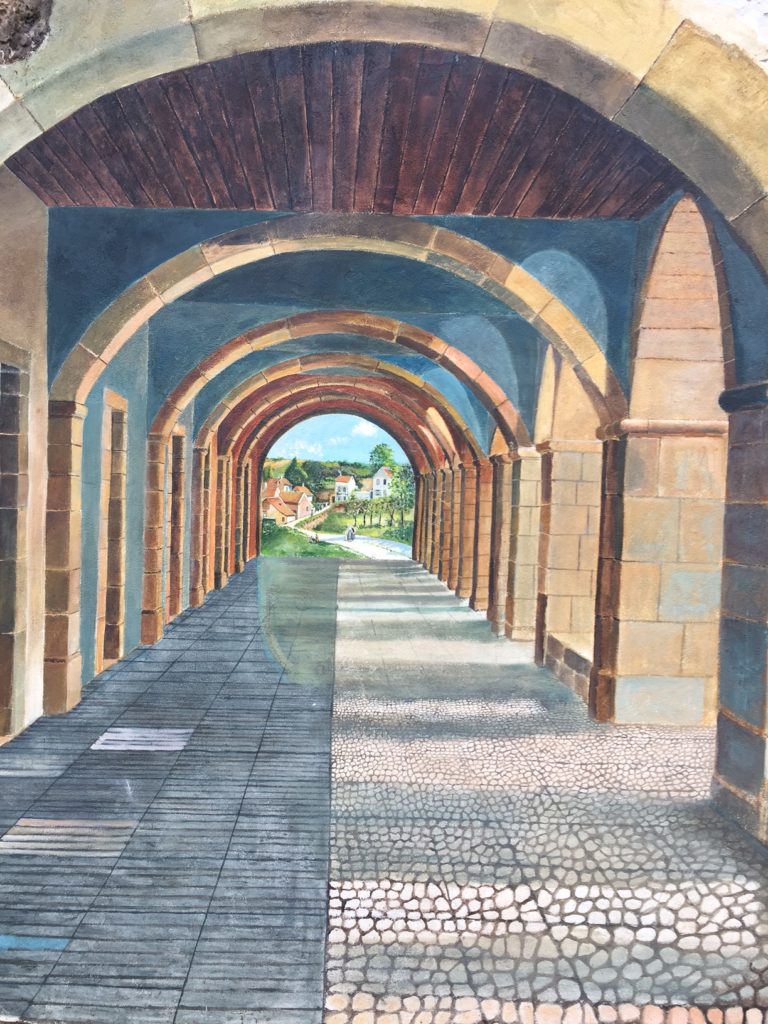

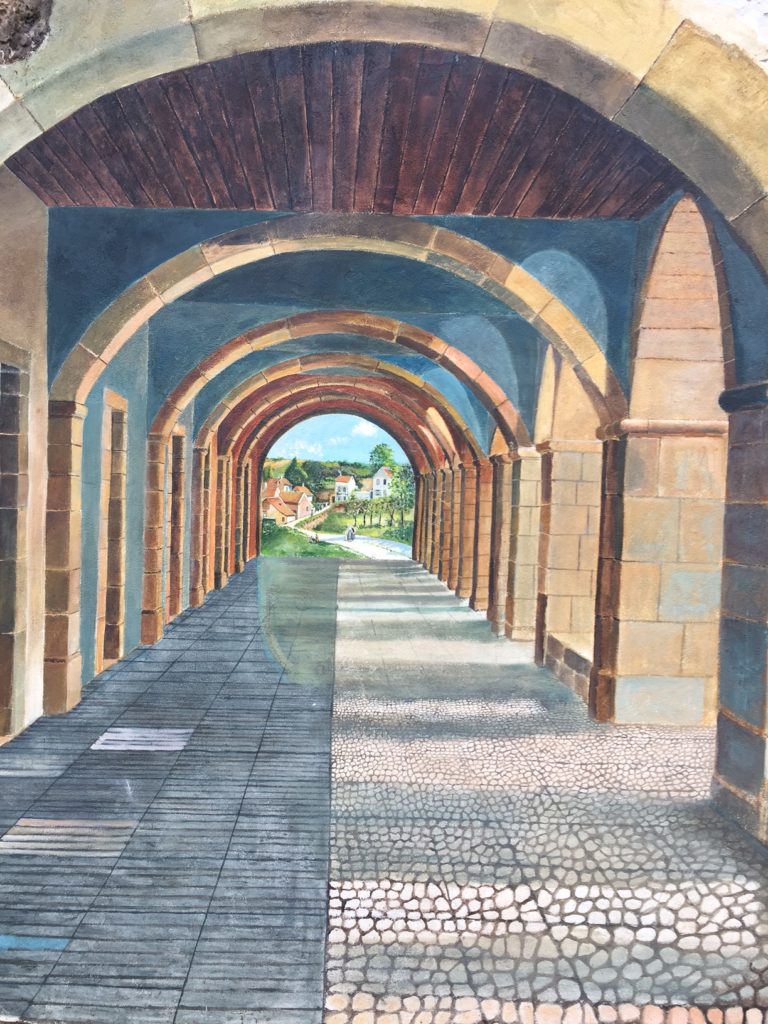

painting in a boarded up window along the Camino Norte

So much happens in a day. I never remembered it all. Sometimes, I forgot to note small moments.

Like the morning I went to find coffee at the tiny tea shop. Walking down from the hills into town,

I took a back street past the market. On a tall, dark, wooden gate surrounding a walled courtyard,

I saw an artfully lettered sign. One narrow door of the gate stood open. Carefully fitting myself and my pack through this gateway, I stepped in and stopped, looking all around me. Small trees stood among waxy-leaved bushes, flowers blushed from soft shadows, creeping vines racing to cover everything in between. Old bricks and iron patio tables and chairs formed stair-stepped seating within the garden. I left my pack and stick and entered the glass doors to the shop.

Inside, all was immaculate, white, pristine. I could already smell my daily eau de parfum, “Essence of Backpacker,” and suddenly felt particularly grungy, my boots dropping trail dirt on the white tile floor. As the frowning woman came to the counter to take my order, I realized the tea shop was connected to the back of a gracious hotel on the main street. I looked around me and saw the well-dressed guests at their tables, taking inconspicuous bites of croissant with small forks. Apologetically ordering a coffee, I made a hasty retreat back outside.

Sitting alone in the garden, sipping from my white cup, I studied the tree above me. Here, behind walls, a lemon tree. I had never seen one before. Across the path, I watched the only other soul in the courtyard, a tame rabbit, slowly hopping from its food bowl back to its small hutch.

It wasn’t claustrophobia I felt, but its cousin, Limitation, who had married Expectations. Far too keen my sympathy for the rabbit in the courtyard garden, safe, fed, sheltered. Tamed. Lonely. I felt it from the people inside, as well. Hoisting my backpack, clicking my buckles, I looked back through the glass at the hotel guests, genteel and serene. Lucky to need to stay outside, stinky sweaty peregrina.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

At lunchtime, I stopped at a sidewalk bench as I entered another town. I carried canned paté, light in aluminum, yet packed with protein and calories; I scooped it out with my spork onto torn bread, watching workmen emptying the trash cans at the park across the road.

Each week or so, I sent postcards home, sharing small moments. I sat on the bench and finished writing this week’s thoughts, then tucked the postcards back into the top of my pack. I refilled one of my water bottles at the peregrino fountain, then set off to find the post office.

After several minutes, I realized I might have missed el correo. Stopping in a taverna, I struggled to catch the chauvinistic barman’s attention, who was deep in uninterruptible sports conversation, being ignored barside a common occurrence for un peregrina sola.

After several minutes, I realized I might have missed el correo. Stopping in a taverna, I struggled to catch the chauvinistic barman’s attention, who was deep in uninterruptible sports conversation, being ignored barside a common occurrence for un peregrina sola.

I turned to the transgender woman sitting at the end of the bar, and she patiently gave me slow directions, explaining that the post office was around the next corner and up the street. I had just enough Spanish words to say, “Thank you very much – and the yellow shirt is beautiful on you.” She smiled delightedly, and I got an enthusiastic wave goodbye.

The postal workers were unfailingly kind, all across Spain, helping me to buy my postcard stamps and always wishing me “Buen Camino!” as I struggled out the door in my pack.

wall mural along the Camino Norte

I stepped in and out of experiences like stepping in and out of these doorways, one intention in mind, a slightly different conclusion usually following me out the door, food for thought on every bench and bubbling out of every roadside fountain. As people went about their ordinary lives, I was being given an extraordinary glimpse within, and paradoxically, this closeness felt expansive.

I waved to farmers on tractors in their fields, and they waved back. Yesterday, a farmer backed his blue tractor out of his farm driveway into the road. Then, at his command, his small dog came running and hopped up the steps into the tractor cab with him, and they set off down the road together.

I saw babies whose mothers smiled. I saw old men who did not. I saw old men who did. I saw an old woman praying her rosary just inside the doorway of an ancient church, its heavy Romanesque arches over the doorways depicting pagan images at the tops of the columns, while inside, Jesus still got crucified, classical music softly playing from hidden speakers.

So many cowbells on so many cows; all the countryside sounded like church bells, which also rang out throughout the day. I got to go inside a tiny chapel to San Antonín because a workman was there to patch some plaster, and he waved me in with a quick hand and a nonchalant shrug. The wooden posts were carved with intricate roses, even the stems and leaves. Older geometric symbols adorned the choir loft.

So many cowbells on so many cows; all the countryside sounded like church bells, which also rang out throughout the day. I got to go inside a tiny chapel to San Antonín because a workman was there to patch some plaster, and he waved me in with a quick hand and a nonchalant shrug. The wooden posts were carved with intricate roses, even the stems and leaves. Older geometric symbols adorned the choir loft.

Last night, a grand total of five of us stayed at the albergue in Sebrayo. The hospitalero had left fresh lemons and two hardboiled eggs in the kitchen. I thought about the tea shop garden as I toasted my bread on the stove, sliced an egg onto it, and had a breakfast sandwich as I looked at my guidebook.

This was my last albergue on the Camino Norte. I squeezed lemon into my water, inhaling the fresh scent.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The rich enigma of going deeper within while going without, living outside, living outside the constraints of home and job and roles and expectations, had become a beautiful Gordian knot, loosening and expanding day by day, but always maintaining connection, always flowing. I had no desire to cut the knot, to conquer it by force like Alexander the Great. I only hoped to trace it, to see it for what it was. I just wanted to walk its path.

The rich enigma of going deeper within while going without, living outside, living outside the constraints of home and job and roles and expectations, had become a beautiful Gordian knot, loosening and expanding day by day, but always maintaining connection, always flowing. I had no desire to cut the knot, to conquer it by force like Alexander the Great. I only hoped to trace it, to see it for what it was. I just wanted to walk its path.

At last, here I was, the chapel at the fork in the road where the Camino Norte and the Camino Primitivo split. I stepped inside. So small, this space to contemplate our choices. I sat on a bench in the cool quiet, sipped some water, clearing my mind in the filtered light. I felt ready.

Stepping outside, I met the local woman who stocks a basket of snacks beside the chapel, next to the bench holding a sello stamp tied to a guest register book. She asked if I had water, and I showed her, and bought a plum for a few cents, so she was happy. And so was I.

Stepping outside, I met the local woman who stocks a basket of snacks beside the chapel, next to the bench holding a sello stamp tied to a guest register book. She asked if I had water, and I showed her, and bought a plum for a few cents, so she was happy. And so was I.

In the book, I wrote, “Each her own Camino.” I hiked on, the plum sweet and juicy, as the road led upward, into the high hills. I had stepped onto – into – the Primitivo.

December 4, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Both the owl and the Third Eye are symbols of wisdom. The Camino scallop shell is here a turban like those worn by Sikh gurus, teachers of enlightenment. “Only that life is good in which the inner battle is fought with determination, through patience and wisdom.” (Tenth Guru Gobind Singh)

“The Camino – it is therapy. I go deeper.

I become animal, natural.

I have gone beyond the seasons.”

— Antonia, Cicilian, living in Marseilles

“It’s beautiful to experience the struggle.”

— Jana, 18yo, student from Amsterdam

“All our culture is from this story.”

— Joanna, teacher, Krakow, Poland

“Every year, more people are walking the Camino.

I think that means something.”

— Fred, approx. 30yo, librarian from Versaille

“I will not let you go unless you bless me.”

— Jacob wrestling with his angel, Genesis 32:26

I had planned to crash the Sunday morning mass at the Catedral de San Salvador, the Oviedo Cathedral Basilica on the central plaza, just for the experience. Now I felt like I needed it. I figured my pilgrim’s backpack and walking stick ought to get me in, plus “no hablo Español.” It wasn’t like Catholics were card-carrying or had a secret handshake at the speakeasy door; surely a showered peregrina could attend.

I had planned to crash the Sunday morning mass at the Catedral de San Salvador, the Oviedo Cathedral Basilica on the central plaza, just for the experience. Now I felt like I needed it. I figured my pilgrim’s backpack and walking stick ought to get me in, plus “no hablo Español.” It wasn’t like Catholics were card-carrying or had a secret handshake at the speakeasy door; surely a showered peregrina could attend. For me, after a long night watching Life and Death haggle over the price of a man, it shone. Not the illustrated Christian stories themselves, or the Bible per se, and certainly not the Catholic Church’s long and terrible history of conquest and oppression. The altar was simply about some human being, some man, alive centuries ago, making a creation of beauty with his warm, living hands.

For me, after a long night watching Life and Death haggle over the price of a man, it shone. Not the illustrated Christian stories themselves, or the Bible per se, and certainly not the Catholic Church’s long and terrible history of conquest and oppression. The altar was simply about some human being, some man, alive centuries ago, making a creation of beauty with his warm, living hands. It was the 10am mass, in a smaller, more intimate chapel that was still breathtakingly beautiful. Old stone arches rose above us in our humble wooden pews, windows high above streaming filtered morning sunlight down upon us. The service was in Spanish.

It was the 10am mass, in a smaller, more intimate chapel that was still breathtakingly beautiful. Old stone arches rose above us in our humble wooden pews, windows high above streaming filtered morning sunlight down upon us. The service was in Spanish.