December 21, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

he did not want to serve me

signs were all there

no boots

no packs

filthy pilgrims

tracking mud and sweat

into his bar

but finally

cafe con leche

I warm my wet hands

at the corner table

look at all the faces

in the photos on his walls

friends music

family laughter

he sees

I take my empty cup

back to him

buen camino

he tells me

with the softest smile

Day of rest. Because sometimes the Sabbath has to happen on a Monday. Walked 9 km to a small town, Castroverde, boasting a shiny new albergue with no kitchen towels or utensils, but many flies. So it goes sometimes. But I was third to get a very clean bed, so this was a great day.

I waited for the albergue to open by having coffee and a chocolate-filled croissant and writing my postcards. Once checked in at the albergue, I mailed the postcards for the weekly cost of 6.75 euros, the price of a bed – then went back to the cafe and paid for my breakfast, which I had forgotten to do. We had teased Joanna relentlessly, “Remember to pay for your food!” because she once forgot; Francesca had copped to it, too. So now it was my turn. No such thing as a free lunch.

The hospitality of Spain took some getting used to. I had been quite confused by it, at first. Whether I ordered a full Menú Peregrino, a bocadillo, or just a cafe con leche, from a table or walking up to the bar, I was nodded to – and then left to study my map, enjoy the view, or strike up a conversation. Every time was like a white-tablecloth affair, even just a coffee: my order was brought to me, but I didn’t have to pay immediately. And a check rarely came – most times, I had to initiate payment. And remind the barman what I had ordered. The honor system.

Coming from a world of ordering and paying at the counter, it was easy to forget to go back. At home, you had to order fast, pay fast, and often took your order to go, especially on a Monday morning. But the bars in Spain were filled with men drinking coffee and and talking politics and sports; the markets were jammed with women comparing prices and stories. Payment took second place to meeting up with your neighbors, catching up on family, discussing the world. My take on Spain was that this very traditional society was built on talking face to face, side by side.

Loudly. Bad manners, to yell your political ideology at a coffee shop back home; making your point, in Spain. Seventeen-year-old me glanced up and then smirked over my notebook, pleased to be the quiet one for a change, a spy in the house of love, “gathering clues to be used in the war of the affections.”

I’m on your trail

you’re never alone

one day you’ll slip up

and leave a lip print on a coffee cup

— Was (Not Was), “Spy in the House of Love”

I stopped this morning in Vilabade, and locals opened the 15th-century Church of Santa Maria for us, the peregrinos chatting and taking a rest together in chairs set out beside a food truck.

I loved the churches. I loved the archways, I loved the crazy, colorful, gilded over-the-top altars, I loved all the statues of saints carved in wood and polished smooth as satin, I loved the creaky wooden pews.

I loved the darkness, and the quiet. I loved the windows way up high, that let the morning light filter in. I loved that songs had been sung here since 1457.

muchas gracias, Amigos del Camino, for opening the church

The patron saint of this church was Santa Carmen, protector of sailors and ships, landlocked here, nowhere near the sea. I thought of the ship of stone, waiting at Muxia. I remembered hurling my burden stone on the mountaintop, and wondered about the Camino stone I still carried beneath my water bottle. I felt attached to it, like I carried it for a reason; I just didn’t know what that reason might be, yet.

Tucked away along the side aisle stood Santa Barbara. As always, she was portrayed with strawberry-blond hair, like mine in my youth, dressed all in red. I liked her as the Lady in Red, the color of blood and fire and passion. Typically portrayed carrying the tower where she had been imprisoned (now reduced to the size of a doll’s house), she stood holding the sword that had been used to cut off her head. She claimed the symbols of her suffering as her raison d’être, literally her reason to be, moving beyond them, a self far too expanded to be contained now, powerful enough to take back the weapon of her own destruction.

I marveled at her. “This is Santa Barbara,” the local woman told us.

“Yes, and this is Barbara, our Barbara,” Christoph had said beside me, smiling broadly. “We have our own Santa Barbara.”

Trail-named. An honor. I had been called out to by this name, from restaurant patios and albergue doorways, seeing Joanna or Christoph or Felix laughing and smiling as they did so, but never so christened as in that moment, before the statue, in the church.

I had always hated my name, prior to the Camino. A harsh-sounding Greek name, it meant, “a foreigner, a wanderer, a stranger in strange lands.” It had only confirmed my feeling as an outcast. To make it worse, to me, it had always sounded like the unattractive name of a middle-aged church lady with bad hair and bad clothes. Which is exactly what I was just then. My crewcut had grown out into a wavy mop that I tamed with my Basque-earring’d hat, my hiking clothes utilitarian and not particularly flattering. No flowing red robes, my sweaty tanktops. No more golden mermaid hair of my younger days; this Sampson had met too many Delilahs-in-disguise, so I’d chopped it off myself, hoping to avoid being noticed any more.

But like my bushy hair, I was trying to grow into my name. I had decided to embrace “The Wanderer,” reclaiming my birthright, before I left home. Wanting to write again, I had created a website where I could chronicle my great escape plan, posting essays describing my thoughts and feelings as I contemplated making a break for it, ditching the ivory tower of the American Dream for my own personal dream: to see the world, and write about the world’s people.

A lover of Pablo Neruda, the great Chilean poet, I named my site after my favorite line, his words etching themselves across my heart:

Our love is like a well in the wilderness where time watches over

the wandering lightning….

— Pablo Neruda

I wanted to live that poetic image, write about the instances of synchronicity in our lives, those moments when we are thunderstruck by understanding, finding and drinking from that deep well where we learn to care more deeply…because we are connected.

I named my website “wandering lightning.” Having purchased the domain and set up the site, on a hunch, an intuition, I felt drawn to look up a translation of my name. Not my first name – my middle name, Lynn. I’ll never know why I decided to look it up; it had always been a bland segue between my irritating first name and my honorable last name, the name of my Viking forebears from Denmark. So I was shocked, spooked, and thrilled to find out that the Danish word “lyn” – was the word for “lightning.”

My name was Wandering Lightning.

In Spain, I learned that, having been burned, Santa Barbara just happened to be the patron saint of trial by fire. And of lightning.

gathering clues to be used in the war of the affections

I’m a spy in the house of love

I won’t be refused

I’m waiting for your heart’s defection

— Was (Not Was), “Spy in the House of Love”

Santiago Matamoros is the warrior incarnation of Saint James. A folk-hero fiction of the Reconquista, he is typically depicted making a great leap astride his white horse, his sword raised in the midst of battle.

December 21, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

- Hike from 7am to 4pm.

- Dig into your pack for your food bag.

- Find an unfinished package of dried apricots.

- Eat most delicious apricots ever.

- Apricot Surprise! buen provecho

December 15, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Then, in that hour of deliverance, my heart spoke. Does not such a country, and such defenders of their country, deserve a song?

— Francis Scott Key

A day rich in weather…fog, mist, water in the air and underfoot on the trail. All day, I walked writing a song. Svend should have seen me go under my hood, a student of my previous day. By the time I reached A Fonsagrada and Podrón, the song was leading me.

Joanna had told me yesterday that she envied my ability to change my life. She said it was not so easy in Poland; many choices, like returning to college, a career change, were subject to approval by governmental agencies. I had no idea. She said she was only teaching now by a miracle, a new private school that worked with her on taking certification courses. If not for this unique opportunity, she would still be in her old, miserable job. “Many people in Eastern Europe see America as a land of this opportunity – to become who you wish to be.” Even if I didn’t always behave like an American, I clearly saw that I thought like an American – entitled to be free.

Free to do whatever I damn well please. I gave 17-year-old me a stern glance. Released is not free; it is unmoored, unchained. Unless I chose to rise, I would just remain forever adrift. Homeless.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As I neared the albergue, a cab pulled up in front of it, and three peregrinos hopped out, pulling backpacks from the trunk and hustling inside. I quickened my pace and stepped in at the door behind them.

All three were haranguing the hospitalera, who was becoming overwhelmed and frustrated. She saw me at the door, and I approached her desk, saying quietly, “Buenos dias; cama por uno persona, por favor?”

“Uno persona?” she confirmed. I nodded, and she waved me in, past the arguing cab riders, who threw a new fit as I followed her up the stairs. Apparently, they didn’t know that pilgrims who arrived by foot always had precedence over pilgrims arriving by vehicle, in the municipal albergues; no reservations accepted.

I was escorted to the last bed in a room for four people. And who did I find in the other three bunks? Cordula, Christoph, and Joanna. Surprise and delight filled the room, and filled me. I had arrived just in time to go to mass, where the priest would give a Pilgrim’s Blessing that night.

I sat next to Christoph as the service began. The mass was beautiful, simple. At the end, the priest called all peregrinos to join him at the front of the church. We stood before the small congregation, while he blessed us all – the jerks and the arrogant, the cab riders and the song writers, the beautiful souls and the wise map makers and the ones who would be monks. The psalm the priest chose for us he called Pilgrim’s Psalm, in fact the 23rd, which included images of being led beside still waters, and guided along the right path. “You have prepared a banquet for me in the sight of my foes. My head you have anointed with oil; my cup is overflowing. Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life.”

I thought of the pilgrim’s dinner before the Hospitales Route, our cups overflowing with wine, a banquet prepared without my having to plan a menu or lift a finger, everyone invited. I knew that the anointing with oil was an historic Jewish rite denoting a chosen king, interpreted as a personal blessing. I remembered my blessing on the mountaintop. Goodness and Mercy were doing their best to follow me, but I was ducking them at every opportunity.

I tuned back in as the priest gave us his Pilgrim’s Blessing: “…Help these pilgrims on their way to Compostela. Guide their footsteps with your kindness. May your shadow protect them during the day and the light of your eyes shine on them by night, so that they can happily stand before the tomb of the Apostle Santiago.” My printed translation of the blessing began with the typo “Lord Good.”

Lord Good. It touched my heart as we stood, pilgrims all together, for endless photos, the priest happy to take a picture for each peregrino with their own cell phone camera. Nonetheless, I did not hand my phone forward. I held the moment of blessing very close, trying hard to remember it. I didn’t want a picture. I wanted this blessing to leave an image of itself within me, forever. Plus, having my picture taken annoyed me, and I just wanted that part over. I was tough to bless.

Even so, afterward, an elderly woman with a palsied face reached out to me. A member of the local church, she had stayed, sitting alone in the pews while we had our pictures taken. Why she reached for me specifically, I could not say. She took my hand, then my face, and kissed both cheeks, saying gently, “Buen Camino,” then kissed me on the forehead, one last time. As she walked out, she turned and blew kisses to me, out of sheer love.

In my case, maybe for luck, as well. “Good Way,” she’d blessed me. Basic Goodness: I wondered if

I could actually learn that meaning of Life this time. Apparently, I needed a lot of repetition for the blessing to stick with me.

Christoph had given me excellent words of wisdom about “my American” dilemma. We agreed that we detected a certain loneliness in Ben, that he seemed desperate at times, and quite sad; being American just added a layer of awkwardness and blundering. “I think he is doing the best he can,” Christoph had advised me, kindly.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I walked arm in arm with Joanna back to the albergue at the end of the evening. As we came upstairs, I saw Ben taking off his boots. “Hey,” I said softly, without hostility, giving a little chin nod, the quintessential American greeting. I tried hard to put that light into my eyes, to shine some kindness his way, here in the night. He was caught off guard. Close enough, I thought, walking on to my room.

Joanna was now stretched out on her bunk. “I wrote that song, about your sad burned trees around the long lake,” I told her. “Do you want to hear it?” She was all ears. And adorable smile.

in my mind today

I must find another way

where the trees that were on fire

bloom with butterflies and briar

where the walking is the day

where the journey is the way you walk it

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

on my wall there hangs a shell

reminding me to walk it well

unexpected twists and turns

the mint is sweet, the nettle burns

between the mountains and the sea

every shrine and every chapel a cathedral

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

en mi corazon, me das El Camino, me das El Camino

— “El Camino”

“Oh sing it again – I want to record it!” Joanna cried, pulling out her phone. I sang it again for her, my enthusiastic audience.

“Do you want to hear another?” I asked, laughing.

“Oh yes!” she said.

From the next room, a loud rustling of unpacking could be heard, interrupting our recording session. “Shhh,” I heard, “Barbara is singing. Be quiet.” I looked out. It was Mauro in his bunk. He told me he loved my voice, and to please keep singing. I think I sang him to sleep; he was feeling sick, so maybe in this way I passed my blessing on.

A Fonsagrada – “To The Sacred Fountain.” The legend we heard was that Saint Francis, himself on pilgrimage to Santiago, had gotten sick and stopped there, cared for by the locals until he recovered; in return, he had blessed their fountain, and it ran white with rich milk to feed them. A banquet, their cups overflowing.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

“Oh no! I missed it!” was Christoph’s response when Joanna later told him I sang for her.

“Don’t worry,” I told him, looking up from my notebook atop my upper bunk perch, “we can sing again; singing is fun.”

And I was dumbstruck to hear myself in that moment – singing is fun. Why had I never said this before? Performance anxiety, I supposed. A hundred small disappointments, I lamented. Singing was my mother’s claim to fame, not mine, I backpedaled. Well, not any more. Listening to myself along the trail, I had heard an echo of my mother’s rich alto voice rising in my 51-year-old throat. Her unintended gift to me.

I looked out the small window at the stars, and was thankful for the gift of singing: music, welling up within me like a fountain, everywhere I went. The perfect instrument for my poetry. The Pilgrim’s Prayer had concluded with, “May we joyfully end the way that we are trustfully doing now.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As I walked along, late in the morning, I heard a familiar voice behind me: “Hola, Chicka!” I turned to see Francesca striding down the hill behind me, which quickly rose again in a new hill, the rolling stroll we had entered now in Galicia. I ran back down and met her in the hollow, and we hugged tightly.

“I thought you were going to walk the Norte!”

“Right, that was my plan, but then I so wanted to do the Primitivo, you know?” Francesca had been walking long days, over 30 and 40 kilometers daily, trying to find beds in the limited number of albergues on the Primitivo. Still, we were so happy to see each other, to walk together again for a few hours, to hear each other’s stories. She was delighted to hear I was writing songs; I had missed her London sass.

As we packed up from our lunch break, we were joined by a most unlikely third wheel: Ben. I introduced him to Francesca, who eyed him suspiciously upon hearing that he was an American. She had just told me, “Your countrymen are not doing much to disavow the stereotypes of Americans abroad. In fact, you’re the only one I like.”

We set off down the path together. Because I had been kinder to him in cafes and albergues, Ben now bravely struck up a more real conversation. “I heard you singing the other day; that was really good. Is that what you do? Are you a singer?”

“You mean on stage? I have, in the past.” I looked over at him. “But it doesn’t pay anything, unless you give up your whole life to travel around, go on tour.”

“You don’t do that?” he asked.

“No, I have a family, so I found a day job instead.”

“So what work do you do?”

I remembered answering this question when I took my oldest daughter to her college Freshman Orientation. We were sitting at a table of other parents, and I remembered their faces, and my daughter leaning over to me after I answered: “Way to kill the conversation, Mom.” It was true; the parents didn’t talk to us after I told them.

“Did. I used to work with homeless people. We had a community resource center where people could come to eat, take showers, get their mail, lots of support services.”

Ben didn’t bat an eye. “But you don’t do that any more?”

“Nope. I decided to do this. So I quit my job, sold my house, and bought a plane ticket to Spain.”

Now Ben batted an eye – both of them, blinking in shocked surprise. “You sold your house? I mean, most people in America, they wouldn’t….”

“Yeah, I know. I’m a bad American. I gave up everything I owned. Well, except the jeep.”

“Well of course not the jeep,” Francesca chimed in.

“Right,” I agreed.

“Wow,” Ben replied, clearly considering this new information. “So you sold your house – but you have a family?”

“Yeah, but they’re grown people. They have homes of their own, now. Except my youngest son. And he’s in high school; he’s living with his father.”

Ben was thoughtful for a moment. “I can’t imagine doing that. My wife and daughter wouldn’t go for that.”

“Most Americans wouldn’t go for that,” I agreed.

He was a dad; I smiled. Ben talked about living in San Diego, the cultural pressures to live in the right neighborhood, send his daughter to the right school, those dinner party conversations about the work you do. He was feeling particularly boxed in by work. Francesca and I listened.

Ben asked about the work of the resource center. I told him how we ran it, the programs, having to ask people to leave for the day if they were intoxicated or behaving in ways that made others feel unsafe.

Ben pounced on the idea of homeless people being alcoholics. Francesca immediately explained that didn’t apply to everyone.

“So many issues contribute to homelessness,” she countered. “You don’t become homeless just because you drink, or you lose your job. You become homeless if you lose your job AND have no money in savings AND have no network of people to help you until you find another job.”

I agreed. “Homelessness is a house of cards. It’s not very solid to begin with, and then any combination of crises brings it tumbling down.”

Ben asked lots of questions about homelessness, and seemed to be learning. I taught him that he can’t say “those people” about anyone unless he wants to engage in unhelpful stereotyping. He got it, that it was a phrase of judgment and distancing, a tool for alienation, and even hate.

Whoever teaches learns in the act of teaching,

and whoever learns teaches in the act of learning.

— Paulo Freire

Francesca and I got a glimpse of the impact when he casually mentioned having served in the Israeli Army, when he was younger and living in Israel. It didn’t matter in that moment what our politics were: we exchanged a glance, imagining this simple guy not more than a boy, carrying a gun, facing war with the Palestinians; this Jewish man trying so hard to fit in and gain acceptance in his San Diego neighborhood, in sunny blond Southern California. America the Beautiful.

oh say, does that star spangled banner yet wave

o’er the land of the free

and the home of the brave?

— Francis Scott Key, “The Star Spangled Banner”

Just before we parted ways, feeling comfortable and trying to be funny, Ben made a comment on something Francesca and I had just said, tagging in with, “Women!” And I did not eviscerate the man with my titanium camping spork, nor did I allow Francesca to gouge his eyes out.

“Ah – ah – ‘Those People!'” I reminded him.

“Hey, you’re right!” he responded in total surprise. And to my total surprise, we all got to laugh together, before waving goodbye.

As I walked on, I remembered a quotation I had once written on the whiteboard for ArtSpeak: “Every blade of grass has an angel that bends over it and whispers, ‘grow, grow.'” It was from the Talmud, one of the beautiful, poetic holy scriptures of Judaism.

Before I reached the albergue, I had written another song. Mostly, it was about my kids, about what it felt like to be a parent; it’s also a reminder to myself, to look past people’s fears and find that sacred spark of light shining in every person, sometimes tucked away into a hidden, secret place, watched over by the whispering angels of Lord Good, and the Tree of Life to which we all belong.

every blade of grass

has its angel bending low

whispering so soft and low

grow…

every falling star

is a dream I dreamed of you

how I wished you would come true

glow…

Life takes hold and Life moves on

learns to walk and learns to run

but I’m still whispering to you

grow…

shoot your arrows to the sky

spread your wings and learn to fly

climb up strong and climb up high

grow…

you’re the sun and you’re the moon

all my harmonies in tune

starlight woven on a loom

you glow…

Life takes hold and Life moves on

learns to walk and learns to run

I’m always whispering to you

swim your waters that are blue

build the fire that is you —

your life’s a dream that has come true

and you glow

— “Every Blade of Grass”

December 15, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

The Camino that can be measured

is not the Camino.

The Camino that can be mapped

is not the right road.

The Camino is not a road;

The Camino is a way.

Free. This Moses came down from the mountain and checked her tablets of wisdom at the door, rejoining the dysfunctional emotional bacchanal already in progress. Golden calves come in many forms – and there’s nothing like a gilded mirror to catch your eye and help you take a good look at yourself.

My mirror was a middle-aged man from California, a name-dropping class-chaser perfectly cast in the role of “Obnoxious American.” Loud and awkward as the worst tourist, he walked up into the holiest parts of the cathedrals where only the priests were allowed; when he asked us to explain what the Stations of the Cross were, his response was, “Oh yeah, when I was in Jerusalem, I saw those.” I turned away with my hands over my cheeks, fingertips rubbing my temples.

I, too, came from the mythical golden land of plenty – America. And I struggled with America. Having grown up poor, working in restaurants for tips and in nonprofits for next to nothing, I saw class as clearly as the lines demarcating lanes on our highways. But to the world, America tried to hide its poverty like dirty laundry in the closet when company’s coming. America was embarrassed by me.

What I had picked up along the way was summarized in a philosophy popular among nonprofit providers a few years back: learn the hidden rules of class. You couldn’t just change lanes. These weren’t lateral moves. If you tried to rise above the station you found yourself in at birth, you needed to be able to “pass” as one of “them.” You needed to learn the secret cultural language spoken by the class above you, because it took a complicated password to truly gain entry.

If you couldn’t pass, you’d be stuck in class pergatory, unable to get off the elevator at the higher floor where the party flowed with milk and honey, but now seen as having renounced your old friends, old neighborhood, old food stamps and Medicaid life for “something better.” Which was interpreted within the poverty class as, “You think you’re better than us.”

Unfailingly, people working in those nonprofits, social workers, counselors, housing providers, viewed this journey in one direction only: “Going up?” Like your own personal doorman, they tried to prepare you with hints for the great success that awaited you – if only you would change your clothes, cut your hair, take these classes, get that job, follow the invisible blueprint for success. No one seemed to take the time to learn the language of the class below. Or its values.

Attempting to liberate the oppressed without their reflective participation in the act of liberation is to treat them as objects that must be saved from a burning building.

— Paulo Freire, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed”

When I was an addiction counselor, I was astounded at the formulaic approach used to help people leave their habits behind. Actually, I was deeply disappointed, by a lackluster strategy of dry evaluation, boring educational materials offered in group settings resembling restless high school classrooms, and inane, chirpy taglines like “fake it ’til you make it” and “one day at a time,” when for some people, the thought of getting through the next 10 minutes was a white-knuckle experience, let alone an entire 24 hours. I knew staff, in recovery themselves, who swore by those mantras…so who was I to look down my nose at their beloved catch-phrases?

America – Love It or Leave It. We were a judgmental, opinionated, bumper-sticker society of self-indulgent rich kids high-fiving a never-ending adolescence; this was my judgmental opinion. Even our reformed addicts were arrogant in their sobriety. How would we ever heal our race and class divides when we were a nation of know-it-alls?

The truth was, I was deeply embarrassed by America. No longer a scrappy young upstart of a country, hungry and idealistic, we had become a soft, smugly comfortable middle-aged yes-man, combing over our money to hide our thinning values, driving a top-down, cherry red midlife-crisis through the world at reckless speed, sucking in our collective gut of wasteful overconsumption to try to seem hip and cool whenever the Scandinavian countries walked by.

So upselling the American Dream to homeless people was a tough pitch for me. It wasn’t completely a lie; it just wasn’t as accessible as it was portrayed to be. Little red, white, and blue lies. The corrosive lies of America’s beloved prosperity doctrine, which twisted religious faith by proclaiming that those who loved God most would be rewarded most – in unsequenced, unmarked bills, or by direct deposit to their off-shore bank accounts. I found the whole system profane.

If the structure does not permit dialogue, the structure must be changed.

— Paulo Freire

Rather than participate in counseling programs I just couldn’t buy in to, to no one’s surprise, I went slightly rogue. Not enough to violate ethics or endanger my counseling license. No, just different. A third generation artist, I took my experience and my community college education, my “connections,” and created an open art group at the homeless resource center.

We created a refuge for mavericks. The American homeless community is full of artists, people who see and hear the world differently, march to the tune of their own didgeridoo along their own Camino. We called it ArtSpeak; we spoke a common language.

They created their own rules for participation: you had to be kind to each other, and you had to respect the studio, which they called their “sacred space.” We decided everyone was in recovery from something – alcohol, drugs, mental illness, or compulsive spending, emotional eating, or internet fixations. The common thread was recovery from the trauma of homelessness.

We sat around long tables placed together, one big circle, and worked in all different media – charcoal, oil pastels, acrylic paint, photography, and also poetry, and rap. I started us off each week with a quotation I had copied onto the whiteboard. Then we would introduce ourselves by our first names, and comment on the quotation. Love it, hate it, indifferent to it or tangential from it, all comments were valid if they were respectful of the others in the space. The artists practiced speaking up for themselves, in the smallest and safest of ways. After introductions, they worked on their individual art…and often continued talking with each other. The sacred space held.

Now on the Camino, I seemed to have forgotten all the rules. I struggled just to be civil to a man I didn’t even know, whose story I didn’t know – because I judged him by his perceived class. Harshly. Less than 24 hours after declaring myself free. I was trapped in Camino pergatory, because I couldn’t figure out how to rise to my own next level.

The oppressed, instead of striving for liberation, tend themselves to become oppressors.

— Paulo Freire

To be fair, my Camino compadres were struggling with him, also. He kept explaining Our Superiority by telling them things like, “This wouldn’t be a problem in America,” such as the time he had to wait a few minutes at a private albergue for the hospitalera to check canceled bed reservations before she could tell him if he could come in. I had very intentionally ducked him that day after overhearing American-money-solves-everything propaganda streaming from his mouth.

I was mortified, and furious: a jerk in my sacred space. An American On Camino. God help us.

And then I had seen who he was talking to. It was Felix. He innocently introduced us on the spot. “Barbara is an American! From Colorado, yes? This is Ben – he is from California,” he offered graciously.

“San Diego,” Ben started with, as if this meant anything to me, having never been to California. I saw him shift into the familiar American Introduction Mode, where we exchanged opportunities to impress each other. I was already looking for the nearest exit. “What part of Colorado?”

“Many,” I said, turning toward the door.

“Many parts of Colorado?”

“Yup,” I replied, slicing off the conversation as I walked out.

oh say, can you see

by the dawn’s early light

what so proudly we hailed

at the twilight’s last gleaming

— Francis Scott Key, “The Star Spangled Banner”

Blinded by an unflattering reflection of America’s image, I could not see Ben with any of the broader perspective I had just called upon the previous day. However frustrated I was with myself, at least I had finally learned: once off track, ask for directions.

I asked Christoph and Cordula for help and advice. Cordula was a travel writer, and she had walked many Caminos, literally and figuratively. She encouraged me to be direct with Ben, because I was allowing him to make my Camino experience difficult. Christoph agreed, saying he had the same difficulty with other Germans, which made me feel better; we wanted them to remember they were guests in someone else’s country and behave like guests. Instead, they postured, critical and impatient.

I would be direct.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Camino led around a skinny canyon lake, several kilometers long. These reservoirs were created back home by damming a river at the end of a narrow valley and letting the mountains themselves hold the rising water. After a few hours, I saw the telltale floodgates here, as well.

But first, we hiked all the way around half the lake. Up the high hills surrounding it, then down, down, down those hills, until our path connected with the road that crossed the dam itself. The road then led up, up, up and around the other side. It was frustrating, seeing how far you would need to walk and making a snail’s progress.

The long and winding road led through a burned forest. Another familiar sight, this scorched earth. I could see that the fire had swept quickly across the steepest parts of the forested mountainsides, as some of the pine trees were only half-burned. I imagined the conflagration racing tree to tree in its insatiable hunger, driven by a furious wind, like the wildfires I had seen in Colorado. Like those old rages I had felt within myself.

The long and winding road led through a burned forest. Another familiar sight, this scorched earth. I could see that the fire had swept quickly across the steepest parts of the forested mountainsides, as some of the pine trees were only half-burned. I imagined the conflagration racing tree to tree in its insatiable hunger, driven by a furious wind, like the wildfires I had seen in Colorado. Like those old rages I had felt within myself.

But it was impossible for me not to see the new growth, as well. Bright, pale green ferns blanketed some of the protected groves; Spanish heather reclaimed blackened hillsides, butterflies dancing over the lunar landscape. The forest hues now ranged from orange-dead branches to coal black trunks to new and vivid green, and the contrast was striking, sad but beautiful.

But it was impossible for me not to see the new growth, as well. Bright, pale green ferns blanketed some of the protected groves; Spanish heather reclaimed blackened hillsides, butterflies dancing over the lunar landscape. The forest hues now ranged from orange-dead branches to coal black trunks to new and vivid green, and the contrast was striking, sad but beautiful.

I later explained to Joanna that there are many species of evergreens whose cones will only open and drop their seeds with the heat of fire. So the burning of the old forest was needed for renewal, new life.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As we approached our next destination, Grandas de Salime, we heard rumors down the Camino of a festival in that town, which meant it might be tough to find a bed. Joanna and I sat drinking coffee at a cafe table, overlooking a grand view of the lake we had just hiked past. Now, Felix and Ben arrived with the news: completo. The albergues were full. There were no beds.

“I think there are still rooms here, if you decide to stay,” I told everyone at the table.

“Here? At this restaurant?” Ben asked, incredulous.

“Yeah,” I snipped. “Many of the bars also rent rooms.” I sighed. “Anyway, I’m going to take my chances, see what’s happening in Grandas de Salime.”

“Well, there’s the solution,” Ben said, leaning back in his chair. “I’ll get a room for us, if you don’t mind sleeping on the floor.”

Joanna looked extremely uncomfortable. “I do not have money for hotel,” she confessed.

“No problem,” Ben insisted. “Besides, I’ll talk them down. We won’t pay full price.”

I started laughing. “You’re going to ‘talk them down’? You think they will change the price for you?”

“Happens all the time at home,” he replied.

“Yeah, well, you’re not home,” I shot back. “We’re going,” I said to Felix, gesturing to Joanna, who was putting on her boots.

“So you don’t want to share because you don’t want to sleep on the floor?” Ben asked. “Felix and I can sleep on the floor.”

“I’ve got no problem sleeping on the floor,” I answered, putting on my pack.

“You won’t share because it’s me,” he added in a tone of voice that almost suggested a challenge.

“NO. WAY.” I glared at him, grabbed my walking stick, and headed out.

whose broad stripes and bright stars

through the perilous fight

o’er the ramparts we watched

were so gallantly streaming

— Francis Scott Key, “The Star Spangled Banner”

Joanna followed. Once we were up the road, Joanna burst into peels of laughter. “Oh, I love you, Barbara. You make me feel free. ‘NO WAY.'”

I laughed with her…but I felt like a fool. I couldn’t seem to stop myself. It was like 17-year-old me was throwing down the gauntlet, and all I could do was watch it happen. My true colors regarding America were streaming until they overflowed…but not gallantly at all. Class warfare was upon me like a fever. I was painting Ben with a very broad brush, thinking he could not change his stripes. The fight was on, even as Joanna and I passed beyond the huge retaining wall of the lake; crazy stars of self-righteousness gleaming in my eyes, over the ramparts we went.

Joanna was the best soul. She taught a course on pedagogy to 14- to 19-year-olds, in a boarding school. Pedagogy is the actual science of education, how it works; it is the art of helping people learn. Key concepts of pedagogy include motivation and critique. The kids came for a full school year, living away from home, learning how to learn.

I mentioned that it seemed they might be homesick. “Oh yes,” Joanna agreed empathetically. “They bring their daily troubles, and I like to talk to them.” Another key to pedagogy is developing relationships of learning.

“They trust you,” I said, a light slowly dawning.

“Yes, I think they do,” she answered with her adorable smile.

“Of course,” I added. “They feel your love. You are a safe person for them to talk to.” Still walking, I looked over at her. “For me to talk to, also.” I smiled back.

Because love is an act of courage, not of fear, love is a commitment to others.

No matter where the oppressed are found, the act of love is commitment to

their cause – the cause of liberation.

— Paulo Freire

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

We had been cautioned by Felix, who had been in communication with a local hospitalero, that we would encounter a swarming mob of displaced peregrinos upon reaching Grandas de Salime. In truth, Joanna and I were excited to see this. Based on the story told to Felix, I reasoned now, “If there are 50 or 100 peregrinos with no beds, they will have to open up something, a park, the deportivo, someplace for us to camp.”

Joanna nodded in agreement, “Yes, I think so.”

So we were disappointed with our anticlimactic reception at the gates of Grandas de Salime: less than a dozen…cows, grazing along the road. “Fi-esta! en Gran-dez!” I danced among the cows in my backpack, making Joanna laugh again. “Let’s see what’s happening.”

We found Christoph and Cordula at an outdoor cafe table, drinking beer. “We were just wondering about you two,” Cordula said, smiling. Christoph came back with drinks for us as well, gracious and without fanfare. We told them the news according to Felix and asked if they had found anywhere to stay. They confirmed that they’d heard the albergues were full, but Christoph had been told by one hospitalero that the albergues were calling the mayor, demanding he open the deportivo, the community gymnasium; unfortunately, the hospitalero hadn’t heard anything back yet.

“We thought,” Christoph added, nodding to Cordula, “that we would go to the mass, and ask permission from the priest to sleep on the church courtyard, you see?” He pointed to a fenced portico surrounding the church just across the street.

Cordula asked, “How are you doing with your American friend?”

“Oh! Terrible,” I shared, giving my most concerned expression, “and – he’s latched onto Felix now.”

“No! Oh no,” Cordula laughed, and Christoph burst out into a wonderful belly laugh.

“It’s true,” I added, relieved to be able to vent my frustration by gossiping about Ben.

“Felix can take care of himself,” Christoph noted with a wry smile. He was met with a chorus of disagreement.

“No, Felix is like a boy,” I explained.

“I want to adopt him and take him home,” Joanna added, laughing.

“Yes, yes,” Cordula agreed, smiling all around. We all wanted to adopt Felix.

“Well, he seems very sensible, to me,” Christoph said, drinking his beer, while I plotted aloud a campaign to “Free Felix.” We would need T-shirts, somehow.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Refreshed, we went to the albergue so Christoph could get an update on the conversation with the mayor. To his dismay, the person he had thought was the hospitalero was simply a peregrino, a guest acting like they ran the place, spouting what should be done, not what they had any authority to actually accomplish. Our only hope now was the church.

Christoph was mortified. He apologized profusely, but we reassured him that his mistake was an easy and honest one. “You didn’t know,” we excused him.

“I should have asked him if he was the hospitalero,” he countered matter-of-factly. I squirmed at my own double standard; Christoph was easy to forgive.

We agreed to meet back at the cafe just before 7pm, in order to go to the mass. Joanna planned to go nap in the park. Just as we were separating, she got a message on her phone: come they have opened the deportivo.

While no one ever did hear from the mayor, the guy running the swimming pool was happy to walk over and unlock the gymnasium door – for Felix. He and Ben had arrived in town behind us, and had gone directly to the sports complex. Felix simply asked, and the pool guy said yes. So now we had a place to sleep.

As I stood at the cafe bar an hour later, paying for a gelato, Felix stepped up beside me, ordering a beer. “I need to get away from this man.”

“The American? Ben?” I made sure. He nodded, taking a long swig of his beer. We talked about how he might do that, first through various strategies, but finally settling on being direct. I told him that we were all behind him in his decision.

“All of you?” He cocked his head.

“Yes.”

“You talk about this?” He was shocked.

“Oh, yes.” I took a taste of my gelato.

Then Felix laughed out loud, looking down at the bar, shaking his head. I would need another

T-shirt for the campaign.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Today’s pedagogy lesson was taught by Cordula, demonstrated by Joanna and Christoph, and practiced by Felix. I just sat at the back of the class and watched, struggling to learn how to learn.

I wandered deeper into the center of the small town, where crews were setting up opposing stages, flyers promoting a battle of the bands. Strings of lights crisscrossed over the streets, and banners promised fireworks after dark. But the battle had already begun.

and the rockets red glare

the bombs bursting in air

gave proof through the night

that our flag was still there

— Francis Scott Key, “The Star Spangled Banner”

December 11, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Gorma finished her morning coffee in the streetside cafe, then walked through the narrow cobblestone streets of the City of Cathedrals until she turned the right corner to find the largest cathedral of all, sparkling from being washed in the night’s rain, each raindrop reflecting the soft morning sun.

She stepped inside the huge wooden doors. All was cool, and dark, and quiet. As her eyes adjusted to the dim light, she saw arches of stone, forming long hallways, more arches joining across from one hallway to another, arches overhead for a ceiling. Everywhere, the walls curved to join hands in high arches, with colored glass pictures in all the windows, birds and animals carved into the stones of the arches themselves, flowers and vines carved around the doorways.

Here rested dark wooden benches, smooth as glass, lovely for sitting and looking. At the front of the cathedral, from floor to ceiling, rose a carved and painted wooden masterpiece of images of saints (who are the best of people), and heroes (who are the bravest of people), and great teachers and philosophers (the wisest of people). It was gilded, which means it was painted all in gold, so that even in the cool darkness it glowed, warm and inspiring, with all the great figures of all those great people. At the center of them all, a tiny baby was painted. For saints and heroes and the greatest of all teachers ever born were all once born as babies sweet, and played as little children do, so Gorma knew: great oaks from little acorns grow.

Beside the great cathedral hall were many smaller chapels, each as ornate and as fine, each different and special, so that many churches were contained within this largest cathedral in the City of Cathedrals, like a gift within a gift, each box smaller until you find the prize inside the final one. So it was within the cathedral, and as Gorma wandered from chapel to chapel inside, she heard a great bell, and saw people all entering one small door, and so, curious, she followed.

She found a seat on a smooth bench near the back and quietly sat down. A priest in beautifully embroidered cape and collar said some words in a language Gorma did not know. Then the people, like a living drum, recited back some words in this same language. Their faces shone, and Gorma knew they said words of love back and forth with the priest, as he encouraged them to be good, and kind, and work hard, being good neighbors to each other, and they in turn agreed to do their best every day, and then they said, “Amen,” which means “the end of these words makes a good beginning.”

Next, the people turned to each other, and with smiles and soft words, shook each other’s hands, offering peace and friendship all around. Gorma smiled and shook hands, and received many smiles and handshakes in return, especially a beautiful, bright smile from the young woman sitting behind her on the very last bench in the chapel. Her smile made Gorma feel very happy, and at last Gorma sat down again, with all the other people, feeling friendly and gentle inside.

Then, to her surprise, a voice began to sing, just one voice, alone and full of grace. And from the last bench in the back of the chapel, the young woman sang a song of hope – for we know the song, even when we do not know the words or the language. A song of hope is so special, so pure, so sparkling in the morning sunlight after a night of rain, that it swells your heart with joy, and your eyes fill to the brim with its beauty, and words will not come…because all you can do is listen, happiness rising inside like the arches to the ceiling, bright and beautiful as the stained glass windows above, warm like the sun coming from behind the clouds at last.

After the song ended, and the last echo of her perfect voice finally faded, the priest led the people from the chapel. Gorma turned to look back at the last bench, but no one was there. And Gorma knew that sometimes, there are great people right here among us today, on their way to becoming saints and heroes and teachers and philosophers, whose images have yet to be carved into the great, gilded altars of the great cathedrals. But their voices and their hearts sing out in the small chapels of the world, unseen, unnamed, precious and holy as angels.

Gorma walked out of the cathedral, quiet and smiling. She and Saint Thomas, her walking stick, left the City of Cathedrals by a minor road, and arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. Outside, the church bells in the little villages rang out the hours, softly in the warm night, so as not to wake anyone from sweetest dreams.

Buen Camino, beautiful Song of Hope.

December 11, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Sail your ship of stone

to bring us all the holy bones

that we must find when we’re alone

Ave Maria

Muxia far from Rome

to the cathedral that once shone

for it is there we will atone

Ave Maria

Ave Maria

— chorus of “Ship of Stone”

I began the day early – but not as early as Felix. As I started down the road, here he came, back to meet me near the albergue, asking, “Did you return the key?”

Feeling in my pocket, I sheepishly pulled out the room key.

“I saved you,” he smiled, reaching for it. “I will return this. Go, go on.”

The Primitivo. Even now, I had options, but I knew which road I was bound for this day. The Hospitales Route was the high road. Crumbling remnants of medieval hospitals for pilgrims, now nothing more than low, broken walls, marked the highest points of the path. Monks during that time offered their caring attention to those reaching the most difficult and dangerous part of the oldest pilgrim journey.

The Primitivo. Even now, I had options, but I knew which road I was bound for this day. The Hospitales Route was the high road. Crumbling remnants of medieval hospitals for pilgrims, now nothing more than low, broken walls, marked the highest points of the path. Monks during that time offered their caring attention to those reaching the most difficult and dangerous part of the oldest pilgrim journey.

As I passed the sites, one by one, along the exposed trail, I heard Felix’s voice, the soon-to-be nurse transported to a past life high atop the Camino Primitivo: I saved you.

Felix was the only one who knew that I had an important day planned, and, true to his generous nature of kind concern, he made sure I didn’t miss it.

The healing road. Ailing peregrinos had only to knock on the door of the nearest hospital/hostel to find rest and accommodation until they were on the mend. Walking on dirt paths and rock, flowers everywhere, I was completely alone, just as I had hoped, with only the butterflies fluttering along ahead of me.

I passed among cows in high pastures, directly through the herds. Horses all bent their heads together, grazing the highlands; the foals trotted over to have a better look at me, but I continued on my way.

The weather on the Hospitales Route was notorious for impassable storms, I had read. Just like back in Colorado, the high country was unpredictable, demanding respect. Yet here I was, hiking familiar alpine-like terrain, under a familiar bright blue sky, the clouds rolling past, burning off.

I had feared the Primitivo would break me. But my legs knew exactly how to hike this path, my feet confident and sure. While the coastal trail had been new to me, I was at home on the top of the world. With no shelter along its windswept ridges, you come face to face with the truth – of yourself. The mountains will reckon.

there is no hiding

from the wind

it searches

everywhere

Midday, I came to the highest elevation I would reach. Stepping away, off trail, I approached the steep mountainside, where it slipped away to join more mountains and hills, as if in endless ranges. The time had come.

Carefully, on a level spot of grassy ground, I emptied out my backpack before I started, laying everything out along my beloved walking stick, Saint Thomas, the broken but strong embodiment of all my doubts about myself and my way in the world.

Standing again, I put on my empty pack, and I faced the sea, that greatest comfort for me.

La Mar. Her vastness lay before me, an endless witness. Seventeen-year-old me stood by my side, silent and sober. The wind sang around us, as I read the three poems.

you are my birth

mother nothing

more

you gave

me

up years ago

and have been

giving

me

up over and

over every

day

since

you do not know

how to mother

a daughter

you wanted a son

I am

the greatest

disappointment

of your young

Life –

a mirror

you are

the greatest

disappointment

of my young

Life –

my mother

I paused, feeling the words echo from the mirror itself. My hair blew around my face, bent over the small notebook as if reading from a holy prayer book.

threw rocks at you

oh my brother

to pay back

every touch

and every torture

young gladiators

circling in the arena

of our mother’s kitchen

for the only chair

at her table

yours

in the end

in the beginning

it was always

yours

as I fell

into wet ditches

where broken

field tile

cut my leg

to the bone

I have walked

with this scar

ever since

always

I remembered, every violation, every sick game gone wrong, every unholy smile and every penetration. I remembered afterward, walking past my mother’s turned back in the kitchen, time after time, my steps like the undead. I remembered how she refused to look at me, to see me.

The wind sang. I thought about the tiny boy, my brother, alone in the night behind unlocked doors, waiting for his mommy to come back to him. To save him.

The wind sang. I stood, remembering how, decades later, she finally told me what had happened to her. And how she had still been unable to stop lashing out at me, forever her lightning rod, taking the fiery fury of her deepest grief, this motherless child, with no one to protect her.

my backpack is heavy yes

I agreed

but I alone must carry it

and if I emptied every item out

still it alone

is heavy

my backpack

is my life

and if I emptied every item out

still it alone

has always been

heavy

I will walk

The Primitivo

I will walk

the far high trail

I will stand

among the mountaintops

and I will empty every item out

and find the stone

that heavy heavy weight

you

have given

me

with all my strength

from all these years

of carrying

my backpack

I will hurl your stone

as far

as I am

from you

Holding that pale, ugly, acned rock in my hand the entire time, I now gave it to 17-year-old me, who took a deep breath, held it for an instant in time, and then threw the heavy stone with the deep-throated sound of a thunderous effort, a yell of protest and a cry for mercy and a rebellious shout of anger and sorrow. It was gone, my inheritance, gone away toward the sea, which was now sending thick clouds up and over the mountains, as if to claim it. I took it as a good sign, that the sea would take that burden, wash it from the mountains, and cleanse us all.

I packed up my backpack, holding and smiling at each item, carefully putting all the basic necessities of my life back into place. Then, with the practiced hand of a peregrina, I pulled my water bottle from its pocket and opened it. I thought of how impossible a task it had been for my mother to embrace me, to raise me, to safeguard me. Flicking my fingers into this holy Camino water and over this holy ground, I said the kindest words I could give to her: “I release you, from me.” I dipped the water again, and touched it to my forehead first, where someday that third eye of wisdom might grow, then flicked it out over the space again, saying, “I release me, from you.” I touched my heart, felt its beating under my wet fingers. I stood a moment, touching my own heart, and then, holding my hands open at my sides as if to the future, I said, simply, “It is done.”

And the wind sang. I listened to it for a moment, as if I heard something, a voice; then I picked up my stick, and I walked on. I crossed over the next mountain. I just walked, lighter.

Huge eagles circled the valley, riding thermals in search of prey, or guarding unseen nests. Suddenly, a gigantic shadow crossed the trail, as an enormous eagle swooped directly over me, so close I felt my hat lift, and heard the rush of its wings as it passed. I shivered at the thrill, ducking to my knees instinctively; but the great eagle was already circling back up above the valley once more. I thought of my father, who always wanted to return as a great eagle in his next lifetime, and I was pleased to think it might be him, come to check on me after my emotional day.

But the emotion running highest just then – was gratitude. Gratitude to understand, and to be able to let go, of all the heaviness of anguished loss, all the times I had to stand my ground and fight, all the times I had given up only to struggle on miserably afterward, all the endless, endless rage.

Gratitude, here on top of the world, under a sky that glowed that amazing blue. I felt strong, and capable. Felt young. Felt like anything was possible.

As I reflected on my small ceremony, wondering if it would have any impact on the world back home, my father’s eagle suddenly flew a circle around the peak before me, and a cloud instantly darkened the mountain.

“Whoa,” I said out loud, stopped in my tracks, as the sun immediately returned, and all the day remained bright, clear.

I knew then – I was free. I had not cast a curse; I had offered a blessing. A wild, strange, wholehearted forgiveness, circling the rock of misery to see it from all sides, releasing the massive weight like the highest, heaviest mountain that even the strongest and fiercest of eagles could never carry. Soaring beyond the deep, dark shadow. The warm light illuminating what could expand and rise.

These coincidences are mysteries to me, and I cherish them.

The song on the wind carried me the rest of that day. It was called “Ship of Stone.” I had entered the days of singing.

To forgive is to set a prisoner free and discover that the prisoner was you.

— Lewis B. Smedes

oh Saint James, first to die

among the faithful, I walk beside

the hayfields like you used to do

what it put your mother through

Mary and the mother of Saint James

crying out their children’s names

the holiest agony in their breasts

that nursed the sacred hearts at rest

sail your ship of stone

to bring us all the holy bones

that we must find when we’re alone

Ave Maria

Muxia far from Rome

to the cathedral that once shone

for it is there we will atone

Ave Maria

Ave Maria

never did Pelayo in his dreams

realize what’s happening

sons of mothers laid to rest

faith of mothers put to test

digging underneath the stars at night

there the bones are shining bright

but even in the silver box

cannot replace the life that’s lost

sail your ship of stone

to bring us all the holy bones

that we must find when we’re alone

Ave Maria

Muxia far from Rome

to the cathedral that once shone

for it is there

we will intone –

A-ve Marie-ia –

Ave Maria

— “Ship of Stone”

December 10, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

a mist

settled over the hills

and never let go

every thing

dripping with birdsong

and moss

August had arrived, warm and wet. A day for going under my hood, to remember all the pictures of yesterday; however, my freedom from Beata allowed space to meet Felix, a tall, thin, 30-year-old Spaniard who walked up beside me and began chatting. Tall and inexperienced in the world, earnest and thoughtful in his black glasses and wild black hair, he soon asked to walk along for a while.

Felix was changing careers and changing his life. He had just left his job, and just ended a relationship with a girlfriend. He was sincerely puzzled by the way that his acts of kindness and generosity had been interpreted as creating a debt owed. He told me he had given his girlfriend a simple gift, a gift he could easily afford on his fulltime IT job, an e-reader so she could read books as she traveled about. He thought it would make her happy. He thought he could make her happy, by giving her caring attention, thoughtful gifts, gifts of himself and his time.

“You didn’t do anything wrong, Felix,” I told him. “You just gave the right gifts to the wrong woman.” He considered this possibility for some time.

Felix was quirky. He minimally filtered his thoughts, words, and actions, which was both refreshingly endearing and odd, almost socially subversive at times, though in a harmless, delightfully Felix kind of way. He was back living with his parents while he enrolled in university, bound by obligation to his family, an uncomfortable fit after his fledgling independence. But it was plain from his stories that the dynamic would not last. Upon visiting an aunt’s home, the family sat awkwardly, hardly talking but disinclined to any other activity. “So I just left,” he said. “I told them, ‘See you later,’ and I went out. Was this wrong? But I could not stay there any longer.”

Felix was quirky. He minimally filtered his thoughts, words, and actions, which was both refreshingly endearing and odd, almost socially subversive at times, though in a harmless, delightfully Felix kind of way. He was back living with his parents while he enrolled in university, bound by obligation to his family, an uncomfortable fit after his fledgling independence. But it was plain from his stories that the dynamic would not last. Upon visiting an aunt’s home, the family sat awkwardly, hardly talking but disinclined to any other activity. “So I just left,” he said. “I told them, ‘See you later,’ and I went out. Was this wrong? But I could not stay there any longer.”

Without filters, we had rich conversation about our life choices, thoughts and feelings, and I found out how much he cared about the people around him, friends with depression, his own struggles. His new career choice: he was going back to school to become a nurse. When I asked him why not a doctor, he answered immediately, “Oh no, I do not want to be responsible for people’s lives. I just want to help them feel better. I want to be the person who pushes them in the wheelchair down the hall, telling them everything will be okay.” I constantly wanted to hug Felix.

Midday, we walked up a hill and found a peregrina eating her lunch at a picnic table beside the road, under a sheltering tree. Behind her, a fence kept the local cows from wandering away; they were having lunch as well, nibbling at the longer grasses in the fenceline.

She hailed us, and so we stopped to say hello and rest a moment. Her name was Joanna, and she was from Krakow. Joanna was one of those ageless people. She had an infectious, gap-toothed grin, a tiny space that reminded me of a legend I had read. The opening was said to be made when the spirit of God passed through the child as they were being born, creating the smile, the sign, of a holy person. She radiated love, and I began to wonder.

I asked her about her day’s trek, and her Camino destination, and she, too, planned to go all the way to Muxia. As we were comparing notes about how far to our evening’s albergue, Felix interrupted us mid-sentence to give us a news bulletin in a very serious voice.

“I think that one is pregnant!” He was bent down, pointing at one of the cows across the fence.

“Yes, I think so,” I confirmed, and then we resumed our conversation. Joanna smiled her lovely smile – and thus she was introduced to Felix.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

By evening, we got to the albergue at Bodenaya, unique and quirky too, known for its communal meals and hospitality. The hospitalero DavÍd met us at the door to give us the unfortunate news that there was only one bed left.

“You have to take it,” I argued with Felix.

I turned to DavÍd. “It’s his first day on the Camino – he just started today. You still do communal dinners?”

“Oh yes,” DavÍd replied, smiling at Felix.

“This is my first Camino friend,” Felix told DavÍd, giving me a side hug. I felt like I was dropping him off for his first day of school.

“He has to stay with you,” I told DavÍd, nodding toward Felix.

DavÍd looked concerned and ducked into the albergue, saying, “Un momento, por favor.” When he returned, I saw that he was very emotional. He held a small yellow arrow pin in his hand.

“This – is for you,” he said to me with a quavery voice, tearing up. “Each day, I give one arrow to a pilgrim. You give – your friend – last bed,” and he broke down sobbing, hugging me. I hugged him back, patting his back. The only words I could think to say were, “So much love…so much love.” I knew they were the truest words; why not say them. I leaned into the embrace.

I walked on through the thickening mist, like carrying DavÍd’s tears and hugs with me. I reached the next albergue just as it was becoming too dark to see. An equally friendly hospitalero introduced me to Mauro, an Englishman with an Italian name.

I walked on through the thickening mist, like carrying DavÍd’s tears and hugs with me. I reached the next albergue just as it was becoming too dark to see. An equally friendly hospitalero introduced me to Mauro, an Englishman with an Italian name.

Mauro had gotten his name from his Italian father. He had traveled extensively, doing custom construction projects to fund his trips. We had a wonderful time talking and drinking sidra at the albergue. He invited me to dinner with him in the misty village just down the hill, and it was excellent – noodle soup, pork and potatoes, wine and bread, homemade flan for dessert.

We talked of our life choices and values, politics, the soaring feeling of cathedrals, writing and music, the satisfaction of living unconventional lives. Another interesting and intelligent person.

I felt so lucky to be meeting the most remarkable companions on my journey.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The next day, Felix caught up to me easily. We discussed the fact that, the following day, we would cross the high mountains of the Primitivo.

I was hoping for a wide open expanse, like a wilderness, a long view, though we were not far from anywhere here, really. I had written words I wanted to read aloud, three poems, and had transferred them into my pocket notebook. I had planned a ceremony, and as I turned it over in my mind, it felt right. I only told Felix that I would need to walk across the high part of the Primitivo alone, that it was important, and I would see him on the other side.

“Of course,” was his only reply, nodding.

Slow though we liked to walk, we were making excellent time, and decided to take a small detour to see the Santa Maria de Obona Monastery. According to my guidebook, it was founded in the eighth century, growing into a local economic and cultural center by the Middle Ages. At one point, during the 13th and 14th centuries, it became, “by order of royal privilege,” a mandatory stop along the Camino for all peregrinos.

As we approached, whom should we see resting in the grass but Joanna. The man she had been walking with, named Christoph, had gone up the hill to the nearby village to see if a key to the church could be had.

As we approached, whom should we see resting in the grass but Joanna. The man she had been walking with, named Christoph, had gone up the hill to the nearby village to see if a key to the church could be had.

At the church itself, we found a sign that explained the monks had taught both formal classes in Latin, philosophy, and theology, as well as better agricultural practices to improve crops and livestock. The building was amazingly well preserved, an old Romanesque structure, solid, imposing.

We didn’t have long to wait before Christoph appeared, jingling a key from his fingers. We cheered, and thanked him for hiking up the steep road, but he only smiled and said, “Let’s have a look, shall we?”

Christoph’s wide smile, dark hair and beard looked familiar; he had been reading in a lower bunk at the schoolhouse albergue where Beata had been unable to stop talking. I felt momentarily embarrassed that he might think she was my chosen traveling companion at the time; then I realized, she was. In my mind, 17-year-old me threw up her hands, making a “get over yourself” face. People would just have to get to know me.

As I looked up from my seat in the grass, a calmer thought came unbidden: “This man wants to follow the path of a monk.” I didn’t say anything, but found it interesting. Maybe he looked like a monk. I, too, had had a similar desire, still considering a yearlong stay in a Buddhist contemplative center in New Mexico. I decided to honor the intuition, or at least respect it. Who knew who he might be.

Christoph opened the church, and we found ourselves in a small entry of utter darkness, separated from the world by a heavy wooden door. But one door further, and we stepped inside a great quietness.

The stones stood silent. Christ hung on his wooden cross, floating above the central aisle, suspended in space and time, his face familiar as a fellow peregrino.

The stones stood silent. Christ hung on his wooden cross, floating above the central aisle, suspended in space and time, his face familiar as a fellow peregrino.

Behind him, a wooden altar held his mother, other saints, and his own painted image, his flaming sacred heart bursting forward from his chest in a golden aura, far more glorious than the halo encircling his head.

Behind him, a wooden altar held his mother, other saints, and his own painted image, his flaming sacred heart bursting forward from his chest in a golden aura, far more glorious than the halo encircling his head.

We slowly walked the interior, taking photos, silently awed by the power of this simple church. And then Felix became offended.

“That should not be there,” he said suddenly, showing Christoph and Joanna a packaged candy hung like a parasol on the elbow of San Roque, the saint who walked his own pilgrimage, to Rome. San Roque always lifted his robes to show he had an injured knee – the same knee I had scraped on a downhill slip one rainy morning. For me, he was the patron saint of skinned knees.

“That should not be there,” he said suddenly, showing Christoph and Joanna a packaged candy hung like a parasol on the elbow of San Roque, the saint who walked his own pilgrimage, to Rome. San Roque always lifted his robes to show he had an injured knee – the same knee I had scraped on a downhill slip one rainy morning. For me, he was the patron saint of skinned knees.

“That is not right, is it?” Felix now asked Christoph, who allowed that no, San Roque should probably not be holding a parasol of candy in the crook of his arm. So Felix removed it, and felt much better. He gave the candy to Christoph.

When we exited the church, Christoph locked it carefully and said he would return the key quickly. Felix offered to go with him. “I will bring us back beer,” he winked. And so, upon their return, we sat in the grass of what may have been the graveyard, under shady trees, near a tall carved stone that was maybe a grave marker or a fountain at one time, and drank golden cans of San Miguel beer, toasting each other and the Camino as we ate the stale chocolate found within the offering to San Roque.

When we exited the church, Christoph locked it carefully and said he would return the key quickly. Felix offered to go with him. “I will bring us back beer,” he winked. And so, upon their return, we sat in the grass of what may have been the graveyard, under shady trees, near a tall carved stone that was maybe a grave marker or a fountain at one time, and drank golden cans of San Miguel beer, toasting each other and the Camino as we ate the stale chocolate found within the offering to San Roque.

A more holy communion was never observed, as we sincerely and joyously wished each other salud and buen camino. The word “communion” means “sharing in common,” after all; and “holy” means sacred, and worthy of devotion. I had no idea at the time how true this would be.

Interpreting my photo of the informational sign later, it quoted an ancient document which noted payments to be made to the monks for their services: “servants should receive cider, if possible.” Amen.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In Campiello, a surprise luxury awaited – a bath. The two albergues had filled their common rooms quickly, so I was offered to share a double room. With Felix. Perfect. We both grinned at our good fortune.

We feasted at a huge peregrino dinner, set out on a long, long table, all together, recognizing and greeting each other, filling each other’s glasses and soup bowls. We delighted in each other’s jokes and songs, including a rousing “Feliz Cumpleaños” to a woman named Cordula, slowly finishing our meal over rice pudding, talking quietly out into the darkening evening. Mauro and Christoph had already met, and were deep in discussion. Joanna was beloved, hugged with joy by a young French couple, themselves newly and deeply en amor.

August is a time, and also a description of honor, meaning venerable, celebrated, esteemed. It can even mean hallowed, sacred. My respect and admiration for my fellow peregrinos was flowing like sidra, an endless waterfall of sparkling personalities and rich experiences. I’d had better moments with new friends here in one month than years at home, trying to connect, trying to maintain connection. Here, I was a peregrina. Here, I was European, if I liked. I was just one of them. Us. Here, I fit in, and felt honored to do so.

I looked down the table at Felix, so happy to sit with all the other young Spaniards, drinking and laughing. So much love. I felt a sense of preparation, cleansing and eating and drinking and enjoying community, before my long sola day in the mountains tomorrow. I stood watching the sunset color the sky before turning in.

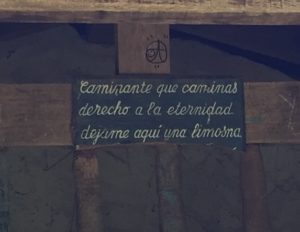

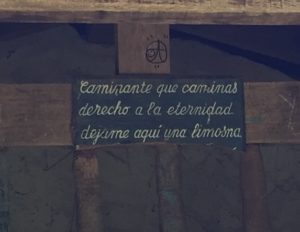

carved corner table in a roadside shrine

I was carrying my own yellow arrow now, following myself, the map pressing itself into the lines of my imperfect and very human hands.

December 9, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

- Check stores, search online, find best of few guidebooks.

- Read and re-read guidebook at home, underlining, making notes.

- Carefully pack guidebook in plastic to keep it dry.

- Carry guidebook in jacket pocket or top of pack to consult easily.

- Day 1: what the fuck! 26.5 km, terrain = 5 on a scale of 5 (which means “Climb straight up a ski run. Twice. Enjoy the blisters.”).

- Day 2: mistake?? 19 km, terrain = 5 (which means “You are old and out of shape, no matter how much you hike or run at home.”).

- Day 3: WAITTT a minute here. I take breaks at home – why am I not taking breaks?

24 km, terrain = 4? NO. I know what this means. Set my own goals each day.

- Too bad – no bed at the albergue, so actually hike 28.9 km. Plan, plan, how to do this?

- There are albergues along the way that the guidebook doesn’t list. Private ones. The cost a little more and save your feet. Stop at 3pm. Daily. Pay the extra 5 euros.

- If the guidebook says 30-36 km, split into two days.

- “Fork right” is useless.

- “Take a minor road” means the writer has never walked this stretch, as they are ALL minor roads.

- If the guidebook says “there is nothing to see here,” the writer was hung over that day.

- All towns with bars are mentioned in the guidebook.

- Stop at every beach. Even if it means missing a bed. Totally worth it. Don’t just walk them. Live them.

- Two 30K days make three nice 20K days.

- Do not choose a resort town as your day’s destination: completo.

- Schedule rest days. Sabbath matters.

- Always take time for a coffee. Always.

- Just follow the yellow arrows.

December 9, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Gorma stood trying to read the signs along the path, signs which had once been written clearly but had now been painted over, scratched out, and worn away, so that their original wording and intent were totally unclear. As she was puzzling over these confusing signs, she heard a small voice, like the sweet chirp of the smallest bird, and so, following the dancing butterflies who twirled down the left path ahead of her, Gorma soon found the source of the tiny sound.

It was a fairy, named Karolin, and she was tending to an injured lizard whose legs were too tired to skitter him along the stone wall beside the path. “Yes, I know the task is hard, and it will indeed make your legs more tired, at first. But if you do the healing work, and practice, you can regain your quickness up and down the wall, I promise you,” Karolin encouraged the lizard. And off he went, with bandaged joints, to practice how to quickly skitter-skitter.

Gorma called to Karolin, whose bright smile lit up the path. Her wings, like a dragonfly’s, quickly brought her to Gorma’s side, and she hugged Gorma with great affection and delight. “Oh, Gorma, Gorma, how wonderful to see you! Always I smile when I know you are beside me.” For Karolin’s great talent lay in healing all the wild ones in her domain, and sweet words of encouragement were a ready part of her medicine.

Gorma walked along as Karolin flitted on her dragonfly wings from one to the next of her patients. Here a blackbird ached with a wing that had been broken; now the wing had healed, but it still hurt the bird to fly. “You must not give up, darling blackbird,” Karolin cajoled. “Your mended wing will be the stronger for having been broken. Do the healing work, and practice letting go the pain, as we’ve worked on all along. You will fly away in no time, now,” Karolin explained, smiling.