November 21, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

the window

the window

bed is mine

I see the old stone

church beyond the fields

the trees and breezes

here I rest

my hat a bowl

to hold my coins

My mind was moving slower, my body faster. I took time to consider my next stopping places, knowing that yesterday’s mileage was much less than I could easily walk in a day now. Looking at alternative albergues, different towns, but also trying to go at least 25 km each day – it was tricky to find the balance. I wanted to push closer to 30 km daily, for the simple reason of strength.

Only a week or so, and I would be on the Primitivo. I studied the route, looking for clues around which to plan, but the Old One wasn’t giving anything away. Well, actually, it was Alex who wasn’t giving anything away in the guidebook…except mileage.

I had hiked 327 km so far; that’s over 200 miles. The Norte was supposed to be 817 km total.

That meant 490 km left to Santiago. I was under the 500 km mark, if I stayed on the Norte. But since I would fork onto the Primitivo – well, well, the book said it was 40 km shorter. Instant Mileage Rewards.

Except I’d learned, numbers don’t mean anything. Tomorrow I would leave Cantabria and enter Asturias; this would be more rugged country, higher hills, less frequent views of the coast and more contact with the Picos de Europa. “It’s not what, it’s how”; now it was “not how many, it’s how hard.”

How hard…would it be, I kept wondering, my boots crunching the miles in the sun.

How hard.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The first time I got lost, I was alone, with no one to ask the way.

This second time I got lost, I was alone. Sensing a theme. But I could have asked the people who left as I was making my oatmeal: “Hey, do you know the way?” I could have asked the person who passed me on the steps as I was tying my boots, a simple, “Which way?” But I didn’t.

They were in a hurry to be on their way, it seemed, and I didn’t want to slow them down. I didn’t want to be a bother. Plus, there were the language issues – French, German, Italian, Swedish, not all with English, me with my fabulous Spanish – and, on top of that, we were all trying to be quiet in the early morning.

And also, I just didn’t bother. I was hardwired not to ask for help. Even though I knew the reality of strength in numbers; I had just experienced it. I had. Just. Experienced. It. The first step is acknowledging you have a problem.

So there I was with Aaaa-lex, the lame guidebook guide, reading the words, “Fork right at the church and keep straight on for 3 km.” That was all. It was like the time he said to leave town “by a minor road.” This was when I started suspecting Smart Alex of not hiking the entire route. A minor road? In these villages, they were ALL minor roads. Fork right at the church; how forking right do I fork? Because multiple little roads passed to the right of the church and took you out of town.

Smart Alex had written a calculus homework assignment instead of a guidebook, and 17-year-old me had had it with this guy. Because, unless he sprung from the pages of the book, pointing you on your way, you had to just try one, eeny meany miney let’s go, walk a solid kilometer, and see if it was leading to the next point. If probability was against you, could you see the correct route from where you were? Even if so, could you actually get to it from where you were? The answers to both of those Camino math problem checks tended to be “NO,” leading to the far-too-often-true calculus answer: backtrack.

It’s a filthy, foul swear-word when you’ve gotten up early, eaten and rinsed your dish, packed your pack and laced up your boots and started off in perfect, cool weather. This wrong road only took me over a wrong hill, not a wrong mountain, and I was sort of comforted by that knowledge, in the way you’re comforted by the fact that your hour of calculus work looked like an elegant solution…it just…wasn’t right.

You had to check your work. Life was a complicated story problem involving many variables. Camino Calculus ran like this:

Beautiful start, pet the movie-set white horse in Spanish pasture, check, pass fairytale farmhouse with obligatory red tile roof and low, warm barn, check, cross over the highway, check, wait, wasn’t that go under the highway?, slow down walking, pass a billy goat on a rope tether and then a ram on a rope, check?, sort of like guard livestock at a less fairytale, kind of dirty, rundown farm, chhh-eck…, cross over the railroad tracks wait, wait this looks way too familiar – where am I headed? Compass check. I’m supposed to be going west. I’m going northeast. Backwards. Heave a heavy, cartoon anvil sigh. Defy your mistake. “I could just keep going, see where it -” You know where it leads: BACK TO THE LAST TOWN. You can see that town from here. Chhhheckk. Open guidebook, read, “Fork right at the church” again and begin to really really dislike ALEX A LOT. CHECK. Summon all your strength to FINE turn around go back past the guard ram and the guard goat who really do not like you now, check-a-checka, climb the pretty sure four-wheel-drive road you just carefully carefully walked down, really?, check, do not baby your knees going back up because you’re storming a mountain until you burn off your frustration at Alex and, then choose to decide this was an excellent early morning training hike for the Primitivo. Whew, check.

Oh, elegant solution, my friend. Seventeen-year-old me was staring at me in disbelief.

Arrive back at the albergue exactly one hour after you left. You have gone nowhere. Elegant?

But, you have strengthened your feet, and ankles, and calves, and knees and quads and okay, you worked your legs. You petted a beautiful horse, saw a gorgeous sunrise – and learned yet another valuable lesson about getting lost: when in doubt, go back to your last waymark.

But, you have strengthened your feet, and ankles, and calves, and knees and quads and okay, you worked your legs. You petted a beautiful horse, saw a gorgeous sunrise – and learned yet another valuable lesson about getting lost: when in doubt, go back to your last waymark.

Go back to the last place you were sure. Go back to the church, and take a different fork to the right.

And guess what – immediately find a yellow arrow.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I hated going back to the scene of my last navigational crime. Plus, I had so many. The first one was easier to identify: dropping out of college.

I did graduate high school, even while working at a pizza place, even while living in a house with adult roommates. My grades prior to my senior year had been stellar, the north star that would guide me on, and into the university. While music had become painful, writing had not, winning me awards already, and I set my sights on journalism, writing for National Geographic, traveling, exploring the world, meeting the world’s people face to face. Telling their stories.

But the price of my ticket out was steep. Neither of my parents had gone to college, and had no idea of the process. My guidance counselor in high school was a football coach who spoke with incorrect grammar. I was on my own. And the internal volcano I was holding at bay kept rumbling, threatening to erupt at any moment, as burning clouds of black ash swirled around me everywhere I went.

I knew college was my one shot, and I had no money to pay for it. So I applied for every scholarship I could find, and I waited. And I waited. For months.

The pressure was intense. Exhausted, overworking, a lonely teenager raging at my fear, I hit the house parties hard. Entering strange houses roaring AC/DC and Led Zeppelin, I drank anything anyone handed me, trying to drown the voice inside that always wanted to scream. I slept with whoever. I didn’t care. I was picking a fight with the universe, even as I knew I was losing that fight. But I was still defiant, throwing chest thumps into the infinite, ready to die like a lonely, lonely warrior.

The pressure was intense. Exhausted, overworking, a lonely teenager raging at my fear, I hit the house parties hard. Entering strange houses roaring AC/DC and Led Zeppelin, I drank anything anyone handed me, trying to drown the voice inside that always wanted to scream. I slept with whoever. I didn’t care. I was picking a fight with the universe, even as I knew I was losing that fight. But I was still defiant, throwing chest thumps into the infinite, ready to die like a lonely, lonely warrior.

By summer, I found out I had patched together enough scholarships and grants to go, a full-ride in the fall, free and clear.

But it was too late. The volcano was erupting. I was on the highway to hell.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As I hiked back up that four-wheel-drive-road, I realized I didn’t like Smart Alex the way I didn’t like calculus the way I didn’t like my non-existent writing career the way I didn’t like how I left college – floundering, without guidance.

As I hiked back up that four-wheel-drive-road, I realized I didn’t like Smart Alex the way I didn’t like calculus the way I didn’t like my non-existent writing career the way I didn’t like how I left college – floundering, without guidance.

When we travel these roads in life with others, we bounce our ideas back and forth, catching each other’s mistakes, sharing experience. When we go it completely alone, we will quit college without talking to any counselor; we will write a library of poetry and songs and stories and observations and have no idea how to get them published; we will keep working an endless series of calculus problems, chasing down a path to a wrong road, down a wrong hill, over a wrong mountain. It will take all our strength to stop, turn, and go back, past eyes that seem impatient with us or critical of us, through places that are not picturesque or inspiring, back up long, exhausting hills just to get back to the starting point again.

A restarting point.

A restarting point.

Sometimes we go to Plan B; sometimes, Back to Square One. Back to the waymark at the church has many names.

It’s about going back to the last place you were sure you were on the right road. The last place you were sure.

Backtracking, unfortunately, is your friend. Maybe try making a few others along the way, so it’s not your only friend. The calculus required is pretty hard on your own, otherwise.

November 19, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Gorma was walking a cobblestone road leading to a tiny village when she came upon a thin monk, bald-headed, robed in the colors of the countryside. His face was calm and peaceful, and he carried his few possessions in his bag.

What Gorma noticed most of all, however, was how slowly he walked. The monk’s pace was so slow that Gorma caught up to him in ten quick steps, so she greeted him hello.

The monk broke into the widest, most cheerful smile Gorma had seen in many days of walking. “Oh, Gorma, Gorma, hello hello! How is your Camino?” His name was Brother Jon, and Gorma told him it was most pleasant, and so they walked together for a minute or two. But no matter how slowly Gorma walked, she could not walk as slowly as Brother Jon. Gorma began to suspect that he was not moving forward at all, but as Brother Jon never stopped walking, this could not possibly be the case. It wasn’t simply stepping in place, because he did in fact move forward, but she could not see how it was happening.

Gorma tried to ask Brother Jon how this trick was done, but he quickly changed the subject, saying, “Oh, Gorma, Gorma, I have such concern! I cannot find the monastery cows! They are the wealth of the monks here, all we have. We use the milk to make delicious cheese that we can sell in the village market – but this morning, as I was tending them, the cows wandered off the grass and down the road, beyond the village, and over the hill. And as slowly as I walk, I don’t know how I will catch them in time for milking tonight.”

“How do you know they went so far, Brother Jon, when we are not yet even to the village gates?” Gorma asked, for she suspected there was more to this story than wandering cows, and more to Brother Jon than met the eye.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, I see things some do not. I have the sight of all who walk so slowly on the way, so I can see what was, what is, and what might be in days to come.” He pursed his lips together in a thoughtful way. “But – it seems my vision lately is so dim, clouded dark as night, my steps are slowed the more for fear I cannot find my way. So while I worried about my sight, I lost the cows my brothers entrusted to my care.”

“Oh, I see,” Gorma answered with compassion now, for those who see what could be possible but cannot take the steps to reach it yet, are often mistaken for the ones who have no real vision at all. So Gorma knew. “But Brother Jon: is it not the pace of all the mystics ever born to walk the way so slowly as you do? For you are not just walking – you’re connecting time with meaning, all your steps a meditation, and a prayer. What does your vision tell you, Brother Jon?”

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, all my sight is dark this day, as dark as if no moon shone in the night. I cannot see the way now, all is empty, all is darkness, all is black.”

“Trust your vision, Brother Jon.” And as she said this, Gorma took her walking stick, Saint Thomas, and with it touched his sandals, so that they almost seemed to glow upon the road. “Your feet must tread a path that only forms as you start walking on. Step forward in faith, sweet Jon, and follow thus, until you find the sight your eyes so plainly see.”

So Brother Jon walked through the village, meditating with each careful step upon the curious words that Gorma spoke, to see what he might see. Step by step, evening approached, the whole day spent in mindful steps, and Brother Jon came to the mouth of a deep cave. He stopped, afraid, but his sandaled feet most clearly urged him on, until finally, he stepped into the cave.

Now all was dark. Brother Jon heard a dripping, faintly now beside him, now behind, and so he stopped again. The silence was so very full it sounded like a whisper in his mind. Looking all around, he could see nothing, only blackness, so he reached into his bag for tools to make a light.

With the strike of that small flame, the flickering light revealed a long and empty space, filled with air and quietness. The flame went out.

He struck again another flame, and this time could see just rock and earth, a cave of time and long-awaited meaning. The flame went out.

So striking for that small flame one last time, he raised his eyes to heaven for a prayer.

And there upon the ceiling of the cave, he saw a herd of wild and beautiful cattle, painted there 10,000 years ago. Red and black, the cows and bulls lay curled, or stood and grazed upon the ceiling. And as he slowly, slowly stepped, his achingly slow steps, Brother Jon thought that he could see the cattle moving. In fact, so slow as he had allowed his mind to be, he could start the see the whole herd softly walking.

So he slowly lead them home, these most beautiful and oldest of all cows, and when the other monks looked up, they saw just Brother Jon and the milk cows returning as the sun was sinking, walking back along the cobble road.

But Gorma knew that he had found the sight he never lost, deep in the depth of the darkest cave, where all that was once wild and dangerous can be tamed with a quiet mind, a spark of vision, and the courage and faith to look up when all you know tells you otherwise. This is the path that is no path – until you step forward, trusting yourself, and the way you walk upon the world.

Gorma walked on, quiet and smiling. She arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. Outside, the night was inky black, dark as the soundest sleep, in the softest bed, in the longest, quiet night. The perfect night for dreams.

Buen Camino, Brother Jon.

November 19, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

sending an arrow

to each of you

they mark the way

but always we

must do the walking

The day started nice and early – breakfast with Jon, the interpreter from Barcelona whom everyone originally thought was a staff person at Guemes, having been asked to interpret for Father Ernesto. It was easy to see why he was chosen. Lively and engaging, Jon asked interesting questions that were fun to answer, demonstrating a talent for inclusion that I saw again and again.

Once on the road, Wolfgang and Svend caught up with us, and we all walked together as I had hoped, because this was their last day on the Camino – tomorrow they would start for home. Jon as well, I found out. Europeans often used their weeks of holiday time to walk a segment of the Camino; the next year, they started where they left off. A wonderful use of vacation…but I would miss them as I continued on my way.

We stopped earlier yesterday, when Wolfgang and Svend found a small albergue, only 12 beds, that still had space, so we checked in for the usual municipal rate of six euros each. Checked in at the bar, across the street – not unheard of, but typically not a promising sign of caring touches or attention for the needs of the weary pilgrim. Indeed, we got what we paid for – bunks, a microwave, and cold communal showers, startlingly refreshing but a bit beyond our modesty. We stood guard for each other at the open doorway. I later asked Jon as we walked: “Was I overly modest to feel uncomfortable about showering with friends? I mean, they’re married. Or would that be okay with European wives? Or…?”

“Nooo, that would not be okay with their wives,” he said with comically raised eyebrows as he shook his head. It was delightfully reassuring.

So now we marched into Santillanes del Mar together, like Dorothy and her friends arriving at a medieval Spanish Emerald City, walking up a cobblestone road into a town of narrow winding lanes, all roads leading to the church before traveling on.

We stopped for coffee and food, and here came Saulomon and Karolin, the girl he had been traveling with when I saw him in Santander. So many hugs, as she was a loving, sweet person, too, and I laughed at the sing-song of Saulomon’s cheeky, “You keep getting youn-ger – sex-ier!” Sexy I knew was not really true, and yet, I’d begun to notice male attention again, after a long time of intentional avoidance. Like the good, cheap wine here, I planned to go sparingly. A wink was as good as a kiss.

As soon as Svend found out we were only 2 km from Altamira Cave, he and I were able to convince Wolfgang to go, and Jon immediately joined in to see this UNESCO World Heritage site. They have closed the actual cave due to visitor impact on its integrity, but using computer-aided engineering, the Spanish government and Museo de Altamira created an exact replica, capturing each bump and divot in every wall surface, to recreate an experience that was truly moving.

To see the bulls, and deer, and horses drawn on the ceiling; an ibex in just a few beautiful, perfect strokes; the hand print of the artist-shaman – the feeling of connection was deep, intense. We were all energized by the museum, not exhausted, and so we headed back to town for more food and drink. Svend and I so enjoyed walking without our heavy backpacks left at the albergue, we kicked up our heels and skipped a few steps in our hiking boots. He and I had begged some private time for “scribbles” as he called them, he for drawing, me for writing, and so, refreshed, we each ran off for a shower (private, and warm) and time to ourselves, agreeing to all meet back together at 9pm, the beginning of the Spanish dinner hour.

Jon’s taste in Spanish food was excellent, his charm absolutely diplomatic, and his attention as a travel companion, impeccable. While Pablo gave me excellent direction to take photos of my stories as backup should I lose my notebook, Jon celebrated the stories of my real life, as I told them to him. He noticed my comfort in being abroad and complimented it, sweetly adding, “Here, you have to taste this,” or simply guiding me through lines with a hand at my back, chatting with a hand on my elbow. I found I loved all this touch, all this closeness, and inside, I silently thanked him each and every time. Human touch felt so good. I hadn’t noticed I’d been missing it.

Thank you for hugs, Karolin; thank you for holding me near you, Jon; thank you for a happy wink, Svend; thank you for a mischievous grin, Saulomon; thank you for making me blush just by walking near, Wolfgang.

Thank you for your hand print, Altamira shaman artist. In the cave, I reached up to place my hand on yours. Thank you for touching my life.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I sat at a table in the small backyard of the private albergue outside Cóbreces. I could have stayed in town, in the crowded abbey with the other peregrinos, no problem. Cheaper. But I sought solitude this day, reflection. Svend would have called it a day to remember all the pictures of yesterday. He and Wolfgang were off to find the train to San Sebastian, first stop on their way home. Jon was going off to meet friends in Gernika tonight, his Camino over as well. Tomas and Ingrid of Austria said they would see me along the way, and I hoped so, but she had an injury to her knee, so they lingered in Santillanes del Mar, where we all stayed together last night, planning one extra day for her to rest.

Our dinner last night was as elegant an evening as I would find on the Camino. We all cleaned up a bit; I dressed up by wearing a clean tank top and hiking shirt, one of my scarves as a summer skirt, and my shower flip-flops to complete the fetching ensemble. We had the six of us with Tomas and Ingrid, sharing bottles of wine and mineral water, pulpa ensalada with vinaigrette, veal with bleu cheese sauce, and flan for dessert, though Tomas endeared himself by his boyish excitement for churros dipped in hot chocolate instead. We talked politics, relationships, made jokes and told stories of quirky characters we had met on the Camino.

This morning, Jon was already gone. The rest of us had one last breakfast together, coffee and toast with jam, and then…I got my pack, and got my hugs. I thanked Wolfgang for letting me tag along, but he surprised me: “Thank you, for walking with us,” he said sincerely, adding, “Don’t forget me.”

Since he was the leader of “Wolfgang’s Gang,” as the funny German girl once called us, I answered, “I’m not allowed to – or you’ll come after me.”

Svend said, “Yes, once in the gang, always in the gang,” then hugged me hard, pulling back to smile, close and encouraging, wishing me well. I didn’t want to leave them. We were the quirky characters we had met on the Camino, sketches come to life, unique and precious individuals.

So here I sat, only 13 km farther down the road, doing my scribbles. I looked out over the albergue’s old stone wall, past the immaculate vegetable garden, across softly rolling hills and directly to the sea.

So here I sat, only 13 km farther down the road, doing my scribbles. I looked out over the albergue’s old stone wall, past the immaculate vegetable garden, across softly rolling hills and directly to the sea.

This was why I had stopped here: the long view. Perspective. I had walked in light rain for hours, within the quiet cave of my jacket hood, reviewing all the pictures of yesterday beautifully etched across my mind, tracing them as if with softest fingertips.

November 18, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I found myself taking a lot of photos of cows. They were for my grandson, who was two-and-a-half and had an inexplicable adoration of cows. I, on the other hand, had a completely explicable adoration of him, and his tiny baby brother: they were the infinitely cuddly offspring of my oldest daughter, Meghan. She was my third child, the center of the spiral of our family. She was our rock.

I found myself taking a lot of photos of cows. They were for my grandson, who was two-and-a-half and had an inexplicable adoration of cows. I, on the other hand, had a completely explicable adoration of him, and his tiny baby brother: they were the infinitely cuddly offspring of my oldest daughter, Meghan. She was my third child, the center of the spiral of our family. She was our rock.

It was totally unfair – but that’s how Life is. Born into a crumbling nuclear family, Meghan was my last-ditch attempt to keep us together, which she did…but just us, her brothers, herself, and me, without their father. Before she was as old as her son was now, her daddy lived far away. Before I was as old as she was now, I was a single mother of three.

Family. The gift that keeps on giving. Even when you don’t really deserve it. I remembered my pregnancy with Meghan: in only thinly-veiled denial that my marriage was failing, I had been clinging to the irrational hope that this baby would change everything, like clinging to a slippery rock just beyond the shore after shipwreck, too tired to keep holding on, too far to swim.

I had been so afraid I would not love this baby, the way I did not love the father. I didn’t understand motherhood. I felt like my heart was damaged, like I was incapable of truly loving, always keeping my distance, even with my tiny sons, both toddlers under three. I took care of all their needs, fed and bathed them, read them stories, shushed their midnight tears from teething or just waking up alone. But I loved functionally, dutifully.

When Meghan was born, labor went fast. Arriving at the hospital in a rainstorm, I endured the wind whipping spray across my face as I inched my way toward the front doors. Finally in the delivery room, my water broke like a crashing wave, and immediately following that wave – here came the baby. The midwife handed her to me as I lay back in my bed. But I lifted her above me in my outstretched arms, and named her on the spot: “It’s Meghan! It’s Meghan.” And looking into her clear eyes, for the first and only time in my life, I fell in love at first sight. Head over heels. I pulled her to me, holding her tight to my heart, clinging to my slippery little rock in the storm of my life.

When Meghan was born, labor went fast. Arriving at the hospital in a rainstorm, I endured the wind whipping spray across my face as I inched my way toward the front doors. Finally in the delivery room, my water broke like a crashing wave, and immediately following that wave – here came the baby. The midwife handed her to me as I lay back in my bed. But I lifted her above me in my outstretched arms, and named her on the spot: “It’s Meghan! It’s Meghan.” And looking into her clear eyes, for the first and only time in my life, I fell in love at first sight. Head over heels. I pulled her to me, holding her tight to my heart, clinging to my slippery little rock in the storm of my life.

Meghan proved a match for her full name, which meant “noble little warrior.” Destined to be an archer, her arrows of trust and devotion hit each one of us straight through the heart, and we finally became a family, the boys and I circling around her protectively. But she needed no protection. Easily their match, Meghan could keep up with “doze bruvvers” when they were running wild, slowly reining them back in.

Refusing a distant relationship, as a baby, she wailed in frustration if I set her down or ducked out of sight for even an instant; we were literally joined at the hip, my tiny warrior princess riding shotgun with me, teaching me a new mother-daughter dance, step by step, in sync, together. Like riding a bucking bronc, this baby slowly tamed me. She reined us all in.

Even so, I was never entirely comfortable with my role of “Mom.” I refused to celebrate Mother’s Day, and so my children grew up giving me Happy Father’s Day cards instead. Chased away by my mother’s irritable words or ignored by her turned back when she was cooking, I learned to despise making meals, and my children learned that asking, “What’s for supper?” was akin to swearing at me, and would garner an equal response. Fiercely independent, I was much more interested in teaching my children to think for themselves and speak their minds than to conform to societal norms and expectations. Fiercely loyal, I offered to do it for them whenever conflicts arose at school, more a threat than an offer as we all knew, which was quickly and nervously dismissed by each child as they navigated their own issues, directed their own lives.

Much as I came to adore my children, I still armored myself in intellect and attitude. I stormed every castle in my heavy boots and long fiery hair. In arguments, I reminded them, “This is no democracy – this is a monarchy. You don’t get a vote.” When I could not dazzle, I intimidated. Yet a chink in my armor existed: a love of goddesses. It was my ultimate undoing.

Much as I came to adore my children, I still armored myself in intellect and attitude. I stormed every castle in my heavy boots and long fiery hair. In arguments, I reminded them, “This is no democracy – this is a monarchy. You don’t get a vote.” When I could not dazzle, I intimidated. Yet a chink in my armor existed: a love of goddesses. It was my ultimate undoing.

They were just so cool, goddesses in all those religions I studied. Tara was not some femmy green-eyed jealous monster in a gossip magazine – she was green, like a dragon, a great defender in Tibetan Buddhism, sitting one knee up, one foot hanging off her pedestal, ready to jump down into the mayhem with you. Shakti was not some sweet little Hindu mama – she was the creative energy of the universe, to your benefit or to your destruction. Plus she always had fantastic wild hair.

What ruined me was the translation of the names. Avalokiteshvara, Kannon, Guadalupe, Tonantzin, all of their names ended up meaning some form of Earth Mother Goddess who offered compassion. My favorite translation belonged to Kuan Yin: She Who Hears the Cries of the World. Every time I read those words, they caught me, brought an ache I didn’t realize I had. Didn’t realize I’d had forever.

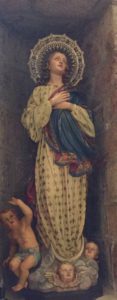

Now, all along the Camino, I found images of the Virgin Mary holding the Baby Jesus. She held her Little One wherever I looked, in seaside towns, in grand cathedrals, in walled cemeteries; in tiny shrines along the path, some no bigger than a dollhouse, where someone devoted, thankful for answered prayer, would refresh flowers in a vase, or light a candle. I ducked under covered porticos to enter low doors, peeped through barred windows, peered through fences and gates, finding the Blessed Mother standing in quiet corners of all the churches along the way and tucked into peaceful bends of the Camino itself.

Now, all along the Camino, I found images of the Virgin Mary holding the Baby Jesus. She held her Little One wherever I looked, in seaside towns, in grand cathedrals, in walled cemeteries; in tiny shrines along the path, some no bigger than a dollhouse, where someone devoted, thankful for answered prayer, would refresh flowers in a vase, or light a candle. I ducked under covered porticos to enter low doors, peeped through barred windows, peered through fences and gates, finding the Blessed Mother standing in quiet corners of all the churches along the way and tucked into peaceful bends of the Camino itself.

She was everywhere. Compassion was everywhere. Holding that baby on her hip, fiercely refusing a distant relationship – with the baby, with peregrinos, with the world. And everywhere I looked, I saw Meghan. Meghan as a baby, clinging tight, and Meghan as…a mommy.

What I had always been seeking, she had become. Where I had been shipwrecked, she had sailed. And I adored her for it.

Goddesses were not intimidating – they were free to love. That was the ultimate source of their power. They encouraged me to keep going, wherever and whenever I found them always the perfect moment, forgiving me for being human…loving me for being human.

I was intent to pay my respects in Santiago and then continue on, to Muxia, and the shrine there to La Virgen de la Barca – The Virgin of the Boat. Some said she appeared to Saint James when he preached in Iberia, to encourage him to continue his work. Other stories contended that when this first apostle of Jesus was martyred, his body was returned to those who loved him in Iberia by La Virgen, in a boat, across the sea.

My favorite version: brought back by La Virgen in her stone boat, the remnants of which could be seen in the unusually smooth, flat boulders landed atop the rugged, stony shore at Muxia. I had to go there, her shrine to compassion built on the rock that held the wild, stormy waves at bay.

jade waves

velvet stone

pouring in upon themselves

the endless vessel

the endless offering

November 17, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

11. Pack more than a costume to wear.

12. Butterflies love flowers; flowers love hillsides.

13. Rest days are sabbath in disguise.

14. Youth will get you up the hills. Age will make the friends.

15. When in doubt, trust the butterflies.

November 17, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

the days

that bring tears

to my heart

are well spent

Today, I played. As I hiked along in the morning, if the view was enchanting, I stopped and gave it my full attention. When I passed a cornfield, I remembered running through the rows as a child, so I jogged alongside in my pack and hiking boots, high-fiving the corn leaves. And on a great downhill portion of the trail, with no rocks or peregrinos in sight, I raised my walking stick like a spear, reared back, and charged down the hill like a little child playing warrior, hollering wildly, then grinning and panting as I hiked on.

Today, I played. As I hiked along in the morning, if the view was enchanting, I stopped and gave it my full attention. When I passed a cornfield, I remembered running through the rows as a child, so I jogged alongside in my pack and hiking boots, high-fiving the corn leaves. And on a great downhill portion of the trail, with no rocks or peregrinos in sight, I raised my walking stick like a spear, reared back, and charged down the hill like a little child playing warrior, hollering wildly, then grinning and panting as I hiked on.

By 10am, the Camino crossed a small beach on its way to steps leading over the next hill. So of course I stopped, stripped down, and waded out into the rocky alcove where the water was sheltered from the fierce waves. I found a perfect shell, and marveled at the black rocks covered in algae. From there, I ventured onto the small beach itself, and jumped and kicked and laughed in the rowdy surf, dropping down to sit under the water, popping up after a wave rolled over my head. The delight of totally solo play is to be totally uninhibited.

By 10am, the Camino crossed a small beach on its way to steps leading over the next hill. So of course I stopped, stripped down, and waded out into the rocky alcove where the water was sheltered from the fierce waves. I found a perfect shell, and marveled at the black rocks covered in algae. From there, I ventured onto the small beach itself, and jumped and kicked and laughed in the rowdy surf, dropping down to sit under the water, popping up after a wave rolled over my head. The delight of totally solo play is to be totally uninhibited.

Refreshed, I got dressed, and as I was toweling off my sandy feet, here came all of my pals tromping by – Pablo, Juan Carlos, Svend, his friend. I called to them to join me, but no one stopped to goof around. I resisted the urge to yell out, “Hike! Hike! Hike!” as they passed.

Too bad. Over the hill, I slogged through loose dunes out to the firm, wet sand of the next beach – beach after beach on the northern coast, and all free. Since this was the actual Camino route, I amused the swimmers and sunbathers, and so amused myself as well, collecting sea shells. This stage of the trek passed quickly, shell by shell, until at the end of the long beach, I clambered up through more loose sand to a boardwalk, sporting a boardwalk cafe. I sat on a wall, my pack leaning heavily against it, and dumped the sand out of my boots as nearby, parents sat their youngsters on the wall to do the same. Boots, pack, and stick in hand, I jogged over the boardwalk to the cafe’s outdoor tables, where I ordered cafe con leche and a sausage and egg pinxcho – my Camino Happy Meal.

A short walk down the boardwalk, I found the embarcadero, and for less than three euros, I got to ride on Scuffy the Tugboat across the Santander bay. Sitting up front, the salty breeze rushed over me as we passed a castle, a huge palace on the hill, and reached our landing right in the center of town. Disembarking, I walked past the cathedral, down a staircase, up another staircase, and found the albergue just a few minutes later, on a tough street of graffiti-covered doors, rusting gates, and crumbling stone walls exposing decaying wooden roof beams.

At 3pm sharp, the equally tough hospitalera opened the door – but only one at a time could enter, boots immediately on the shelf, stick immediately into the tall can, and the price is 12 euros, not 10, no 50-euro bills accepted. Nevertheless – if you smiled and followed her directions, boots here, stick here, cash here, like a strict teacher she would reward you with a smile in return, announcing, “Perfecto.”

The showers were hot, the beds standard-issue metal bunks, the people peregrinos I had met. Perfecto enough.

I looked at one young man closely; slowly, I asked, “What…is your name?”

He grinned a beautiful, foxy smile, answering in a flirtatious tone, “It is me – Saulo-mon!”

“Saulomon! No – you look younger! How can this be?”

“Barbara! You too! You have lost weight – and gained color!”

“Yes,” I said. “And a stick.” I gave him a wink. I told him about my play day.

“Yes, you are becoming 17. Birth-day-par-tee — in San-ti-a-go!” And he gave me a huge hug.

I toured the cathedral, wondering at the Roman ruins underneath, had a glass of vino tinto, bought items at the farmacia, and light, wind-resistant pants for the Primitivo; afterward, I finished all of a fantastic omelette of calamari, mushrooms, prawns, and bacon, a second glass of vino tinto, and of course, fresh bread.

My pizza gut was gone; I was light and lean. I am in Spain, I kept marveling. I am making friends and loving every day. It is almost 7pm, and there are three hours left before the sun sets. So much time. So much time to play.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The kilometers passed more easily with friends. We told each other stories, and the steps went quickly. This morning, I walked until noon with Pablo and Juan Carlos, finding out why they both became policemen, what motivated them. They had known each other since they were 15, and argued and harassed each other accordingly as the stories unfolded.

Pablo had originally followed in his father’s footsteps and drove a cab. The money was good, but something was missing. Always looking for a new horizon, he answered an ad seeking new recruits for the police force, and this huge, straight-forward man was readily accepted – I would assume with outstretched arms. He then recruited Juan Carlos.

Juan Carlos had gone to the university after they graduated high school. His degree: philosophy. So in no time at all, his education rewarded him with a job in a factory. It was a fine job, but police officers were paid more, and so, with persistent nudging from Pablo, Juan Carlos too joined the police force, perhaps with less enthusiasm, but with commitment nonetheless.

It was fun to discuss philosophy with Juan Carlos (who did not speak English) using Pablo as our translator, who I think would have preferred to talk about football, but he indulged us anyway. At Pablo’s urging, Juan Carlos thought to trick me by asking if I agreed with the concept, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” which, I said, I do.

Aha!, he disagreed, illustrating the flaw in this thinking using mathematics, where integers carry a zero (noted .0) that reflects a relationship to infinity, stating that thus, the whole, an infinite number, cannot be greater than the individual, infinite numbers themselves. Poor Pablo.

To which I countered: two people meet and fall in love; what is between them is much more than just one person and one person. In the same way, a flower is beautiful, and two flowers are lovely; but a hillside of flowers will take your breath away. Pablo smiled, amused, as he relayed my words.

Juan Carlos nodded in surprise, mildly impressed, and conceded these points, so I softened my stance by saying, “I am a poet. We are bad philosophers, because we cheat: we see everything as poetry.”

At lunchtime, I walked into the village Boo de Pielagos beside the river Mogro. Father Ernesto had advised that, to cross the river, peregrinos often walked across the train bridge – somewhat dangerous, and illegal, subjecting peregrinos to arrest, but his view was that peregrinos choosing the Camino del Norte were more “creative” than those walking the Camino Frances. I didn’t feel as creative as Father Ernesto might have liked, but I knew that one way or the other, the puente de tren was my ticket across the river.

As I walked the path toward the river, I passed a tiny, elderly woman walking very slowly, carrying groceries home. I offered “buenos dias” as I stepped around her, and she smiled slightly in return. However, a few paces forward, I stopped and walked back to her.

“Necessita ayuda, señora?” I asked in my babytalk Spanish.

“No, perro muchas gracias, peregrina,” she replied.

“Eh, donde es estácion de tren?” I asked.

“Aqui, aqui,” she replied, and, having seen the shell tied to my pack, allowed me to carry her groceries at last, placing her thin hand in the crook of my arm. She led me to the train station, a wayside platform no bigger than a covered bus stop. Her name was Maria Jesus. I would never have found it without her. She gave my arm a squeeze as we parted, adding, “Buen Camino.” I smiled, waving and calling thanks.

At the train platform, I met up with Svend and his friend, whose name was Wolfgang (oh that’s not intimidating, I thought). They were waiting for the train, but had only seen trains passing in the opposite direction. Wolfgang was growing a little impatient. I asked if they had tickets, and they said no. Reading the instructions on a small kiosk, reference was made to loading a card; a free call could be made for assistance.

I pressed the call button just as Wolfgang let me know it wasn’t helpful. A man’s pleasant voice came through a speaker in the fastest Spanish I had heard yet. I asked, in my babytalk, about train tickets, but with the combination of speed and fuzzy sound quality, I had no idea what he said, finally resorting to, “Nada, nada, gracias,” at which point the pleasant voice hung up. Svend and Wolfgang began laughing before I had even ended the call, as they had tried this too; the plan was to try to buy tickets on the train. I did my part by translating the train schedule hanging under plexiglas behind us – we had 45 minutes to wait.

Svend worried that he was out of water, so I offered him some of mine, which he initially refused. I held out both of my still-full water bottles, having emptied only my smallest third bottle, until he finally relented and let me pour some of my water into his bottle. “it will taste a bit metallic,” I explained as I poured. “The iodine makes it clean, though.” So Svend drank. I pulled out peanuts, and shared those as well, and dried apricots, and so began taming my Germans. I felt thrilled, like I had tamed wolves.

When the trained arrived, we all stumbled on, fitting our packs and poles and sticks inside as best we could. We watched the river’s approach, and marveled as we sped overtop. “It’s the first stop, isn’t it, the village Mogro?” Svend and Wolfgang had no idea, and yet, when I hopped off at the next stop, we all got off. No ticket, no cash, no problemo. We had hopped a train. I thought Father Ernesto would be proud. Seventeen-year-old me was – there was no other word for it – stoked.

Thankfully it was correct, and we immediately found our yellow arrows again. So in the afternoon, I got to walk with Svend and Wolfgang. Svend was a paramedic with the Red Cross, and Wolfgang was an editor for an ad agency, and self-employed as well, as a translator. Wolfgang spoke four languages, including an American English that rarely betrayed his native German, and overall, he amazed both Svend and I. They were both married, both fathers, and so we could talk easily about relationships, parenting, grandchildren, and finding meaningful work. We talked of the Camino and its meaning, too, and how the ultimate destination is, of course, death, so the way is, the journey is, all you really have. I told Svend I had come to rely on the guidebook less and on the people more, and he became teary, and we became fast friends on the spot.

I have a soft spot for people who can cry, who can allow their hearts to be touched. I had already begun to have my own teary moments, of wonder and gratitude, even twinges of self-forgiveness for taking so long to get here, for blowing off my dream, for having had cancer and having to give up the soft places in my body where my babies grew, for divorces and bad choices and all the mistakes, all the confusion. In that moment, Svend reminded me that we can access healing tears, like the fonts of holy water at the churches and chapels along the way.

I told them how, last night at the albergue where I stayed, I sat talking with a woman named Aqua for a long time. Aqua was finishing her master’s degree in Dance and Music Anthropology. She taught traditional Lithuanian folk dance in the schools. Aqua reported that, as a result, bullying was reduced, she believed because dancing crossed socio-economic strata, and because the children touched. They joined hands, or held at the waist, and this safe touch changed how they related to each other. It was fun, practicing trust this way.

Aqua had also learned about the Basque social system that gave each Basque person a minimum income that was enough to pay rent, buy food, and visit family to keep their social network firmly connected. So the Basque essentially had no homelessness – because they had enough, and had each other. Trust again. We had talked about homelessness in the U.S. and terrible alcoholism in Lithuania, and what we could learn from the Basque, and from each other.

I told them how Aqua sang a sample of traditional choral music, songs for three voices in a round that traveled minor keys designed to produce a very pleasing dissonance. I liked that each voice could be heard, and added a richness of texture and tone to the overall structure of the songs. Svend is a visual artist, so we talked about my art program for the homeless, and this notion of a pleasing dissonance as visual image, too – contrast, opposition, and the unexpected.

We discussed our Camino guidebooks. I described my English book as written for “peak baggers,” and then needed to explain the term. I suggested Wolfgang should write a new English guide, properly, with realistic daily mileage, and more about its beauty and peacefulness, which, I found out to my surprise, he deeply enjoyed. I would not have guessed this when, taking a photo of an old man working in his garden, I rejoined the walk to Wolfgang’s sarcastic reprimand: “Stealing the souls of the elderly of Spain, are we?” I retorted that I’d asked, but the abuelo couldn’t hear me. Svend smiled broadly, hiking along. I loved them both in that moment.

Buen Camino, Svend and Wolfgang

As Father Ernesto had revealed, the people I had met on the Camino were smart and interesting; they had depth, and curiosity. I had trail buddies. We hopped a train across the river, and made do in cheap albergues, sometimes with cold showers and no kitchens or laundry. Because we got to walk together for hours talking of meaning and purpose, and help each other find our way, making connections even without train tickets, or signs, or yellow arrows. We had each other. We were creating a very pleasing dissonance. It would bring tears to your eyes, if you really listened.

November 15, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

One fine day, as all days on the Camino, the path led beside an ancient stone church. Gorma was drawn to it immediately, not for its great ornate arches or windows, but for its simplicity. Standing alone in the misty fog, it felt very old, from a time long ago, filled with songs and stories she could almost hear. Just as well, it was the Church of San Tomás, and so of course Gorma gave her walking stick, Saint Thomas, a drop of the holy water in the basin near the entrance, so that he might be refreshed, then leaned him against the heavy wooden doors, so they could speak if they wished, wood to wood.

As she turned from the doors, Gorma saw an old man disguised, with white hair, a blue shirt the color of a sunny sky, and eyes trained to hide the truth of suffering. He was sitting at the edge of the foggy churchyard, looking far away into another time, pretending he was studying the birds in the trees above.

“It is peaceful here, don’t you think?” Gorma asked him, settling onto the bench beside him, for she knew he was not at peace, and wanted to see how he would answer.

“Aye, this churchyard could bring peace to the Devil’s own,” he replied, still looking out into the beyond.

“What is it brings you here this day?” Gorma asked him, wrapping herself warmly in her cloak while eyeing his thin shirt in the chill, for she was certain it was not by chance, and wanted to see how he would answer.

“Ah, well a man of Northern Ireland can often be found sitting among the tombstones of a churchyard. Which church is the only question,” he replied. “Just by chance, I happened into this one, along the way.”

Gorma studied him carefully now. “And where will you be going from here?” Gorma asked him, for she knew perfectly well, and wanted to see how he would answer.

“Oh Gorma, Gorma, this is the question that worries like a dog at a bone, is it not? Where to be going from here?” He said his name was Stephen, and he was from the North of Ireland, where things are not always as they appear. Stephen had gained a fortune for himself there, but had lost something precious in the bargain. “Now I wander this road, my way without purpose. This path or that, makes no difference to me, for they all lead here, to headstones in a churchyard. It’s a life wasted, really.” And he let out the deepest, saddest sigh.

“Where is your home?” Gorma asked. “You could go home.”

“Indeed, between Belfast and Newcastle, at the foot of the Mourning Mountains, stands the home of an old man, that I moved into when he passed. This is where I live.”

“But where is your home?” Gorma asked again.

“That’s what I say to you, Gorma, there at the foot of the Mourning Mountains, the home of an old man passed is where I live.”

“Where – is – your – home?” Gorma asked a third time.

“Ah, Gorma, Gorma, the whole of Northern Ireland is home! The troubles, the quiet, the green lands, mountains, and the wild sea. I stay in that house, but my feet get to itchin’, and I have to go out and walk the paths again. I cannot stay in that house! I have no peace!” And here Stephen’s eyes looked fiercer, more determined.

So quick as Saint Thomas learned the thoughts of the old church doors, Gorma took the knife of love that Hernani had given her, and used it to cut the misty shroud of regret that surrounded Stephen. He blinked at Gorma in shocked surprise.

“Your life is not wasted – don’t you see?” Gorma said, still standing, now gesturing toward the clouds above. “You have forgotten what you love, and the tears you work so hard to hold back have veiled your vision. Your vision of your kingdom, Stephen; your kingdom, that place where you truly live. Can you see it now, without the mist obscuring your sight?” Then King Stephen of the North of Ireland rose to take a stand, and looked into and beyond time, clearly and with love, and saw his kingdom standing open, waiting for him to return.

Peace is loving the troubles too. Gorma knew that hard though it may be, we must not squander our talents and fortunes on cold comforts. We must spend them, like our days, in the service of our most noble purposes – what we were born to do. We cannot keep our hearts locked away; a king’s ransom will just as well pay for a kingdom to flourish, after all.

King Stephen looked back over his shoulder at Gorma, and they both smiled. His white hair shone with wisdom and experience, and his sky blue shirt had become his royal cape, tossed over one shoulder as he stepped forward with purpose, head held high, returning at last to his true life.

Gorma picked up her walking stick and walked on, quiet and smiling. She arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. Outside, gauzy clouds passed gently across the face of the moon; but they did not last, and soon the moon shone clearly over the Camino, and far away to the North besides.

Buen Camino, Stephen.

November 15, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I fall asleep most nights

lulled by voices speaking

languages I cannot understand

Two weeks ago, I was saying goodbye to the people I love, planning when I would be back; I was flying away from home, a day of airports in multiple states, multiple countries. I knew nothing but anticipation.

Now here I was. I’d met Begoña that first night, and we were already becoming friends. I hugged and kissed Pauline and Antoine with true love and affection whenever I saw them, my friends from Marisa’s house. Francesca was a treasure, so like my youngest daughter in appearance, so like young me in her choices. Pablo and I planned to share many future conversations. And so many more peregrinos that I knew on sight, some by name, some as The Dane or The French Couple, many friends, even if they were only Camino friends, which could often be just enough for the journey to proceed well.

I noticed I was simplifying my speech in English; it made it easier for others to translate back into their own languages. I did this enough that at dinner one night, everyone assumed I was European of some sort until the French man asked directly, “And where are you from?” and once told I was American, added, “Maybe you will be European by the end of the Camino, no?” I responded that I hoped so, causing laughter and cheers around the table. One can dream.

The Camino unrolled with kindness and laughter and good intentions. But that road paved with good intentions could be difficult to navigate, especially with a language barrier.

When I missed getting a bed at the Noja albergue, I walked a couple hours into the town of Meruelo, where the tourist office guide had said I would easily find the albergue: “You can just ask anyone on the street, so easy.” So I did. I asked several people, and they all gave me the same confused look and reply: “No albergue en Meruelo.”

What the hell. I saw no signs, no arrows, and was beginning to wonder what to try next, when an older man overheard my queries and, by saying, “Aqui, aqui,” with gestures to follow him, led me to a private home. As he ushered me toward a gate that led to a secluded back door, I hung back, giving him a distrustful eye. He appeared somewhat distressed by my refusal to follow, so he added, “mi hermana, mi hermana,” and reluctantly I stepped past the gate and edged toward the door. He threw up his hands and entered the back door, and soon he reappeared with a woman about my age, his sister, walking with crutches under both arms. She smiled and bid me “buenos dias” as she led us slowly out the gate, down a steep sidestreet to another house. They both went inside as dogs barked wildly behind a high hedge of overgrown bushes, behind which several young men sat or stood in a small yard. The young men peeked out through the bushes, speaking in rapid Spanish to each other.

Finally, the older man came out with a young woman of about 20 who spoke English, though somewhat timidly. She said that since it was evening, the man (her uncle) wanted to give me a ride to the albergue, and she would come along so I would not be alone. I thanked her, and explained, as we loaded my pack into the back of the tiny hatchback and I clambered into the back seat, that I had a bed waiting for me at the albergue in Meruelo.

She relayed this information to the man, who shook his head, telling her repeatedly in Spanish that the albergue for peregrinos is in Guemes – we have no albergue in Meruelo. So he proceeded to drive me out of town toward Guemes.

However, as we were leaving town, I saw symbols painted on the back of a signpost, an A with an arrow in Camino yellow (the symbol for “albergue”) with “1 km” painted underneath. I told the girl, “See? Albergue sign! It’s only 1 km. Please ask him to stop.” She told the man, who promptly ignored us both, repeating his line like a refrain: YES, We Have NO Albergue, They Have The – Albergue – In Guemes! So I got louder and louder, speaking over his ridiculously repetitious denial like a lunatic backseat driver hostage, saying, “No, please stop. NO, stop now. NO, STOP AND LET ME OUT. LET ME OUT! HE MUST STOP NOW!!!” Once I reached a fever pitch, aka Spanish Conversational Argument Tone, he stopped the car and asked more quietly, “Oh, she wants out here?”

I threw open the car door before it had quite come to a stop, grabbed my pack from the hatch and slammed it shut as I repeated, “Gracias, gracias, gracias,” closing the car door mid-“gracias” and quickly walking away in the other direction. I had just added an extra kilometer to my walk by letting them “help.” Also, he’d been drinking. But truly, all of Spain drinks, so this was not really a problem of driving per se, so much as a problem of stubborn Spanish opinions. I was becoming a local, apparently.

There is no albergue in Meruelo. Except there is. It is beautiful, clean, serves meals, and is just after the small rio – the road bends right, and it sits beside the cornfield. As the very old man on the quiet country road told me. In his very soft voice. Once I had calmed down, by walking the Camino Standard 2km. Muchas gracias, señor. Buen Sábado.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Guemes. By 11am, I had already put away my boots and taken a shower. By noon, my clean laundry was drying on the clothesline, and I was adding up mileage to see how far I’d come.

Guemes. By 11am, I had already put away my boots and taken a shower. By noon, my clean laundry was drying on the clothesline, and I was adding up mileage to see how far I’d come.

How beautiful is a day of rest. And, fittingly, it was Sunday.

I couldn’t explain to Uncle Meruelo in the car last night that I had a plan, to keep my bed at the local albergue so I could spend the following entire day at Guemes, the Aspen resort of albergues donativos. But Guemes was so much more than that kind of beautiful.

Ernesto, who runs it, is still a “working priest,” meaning he has a job, and also serves his community, and also often reads the Mass, as he did yesterday. Twice. Plus his third Mass, which he calls “Social Mass,” in which he goes to three bars and has a glass of wine at each, talking to the people – because he says reading the Mass is a soliloquy, but these Social Masses are dialogue, and therefore much more important. Thus we met Father Ernesto.

He decided to be a priest at age 15, and was sent to isolated, fractious locations where he would successfully rally and organize the people to improve their situations and their communities. Ernesto was 80 now, and had served on four continents, taking his trusty old Land Rover, with over 700,000 km on the odometer, from remote regions in South America to Senegal in Africa.

In his later years, he joined forces with a social worker in the local prison, who had the inmates growing beans. These they then sold to pay for a remote school – all its needs, books, uniforms, food, everything. In this way, the prisoners were actually caring for these children’s futures.

Guemes’ projects had no funding except donations, Father Ernesto explained before dinner, as we all sat in a beautiful family compound of 75 pilgrims – that could accommodate 100. The kitchen/dining room building was the home where Ernesto was born; everything else had been added on, little by little, buildings or projects, over 35 years. The years I had been taking care of children, and doing social work, so had Father Ernesto.

Guemes’ projects had no funding except donations, Father Ernesto explained before dinner, as we all sat in a beautiful family compound of 75 pilgrims – that could accommodate 100. The kitchen/dining room building was the home where Ernesto was born; everything else had been added on, little by little, buildings or projects, over 35 years. The years I had been taking care of children, and doing social work, so had Father Ernesto.

The intention and impact of their service was all explained with such intelligence, grace, and humor that of course we all wanted to help them. When I left home, one of my dearest friends gave me extra money, saying, “You’ll know when it’s the right time to use it. Splurge.” So I gave 50 euros to Ernesto’s children and prisoners and albergue. I did it on the sly, just tucked the folded note into the donation box anonymously.

Part of me wanted to join them, help with this work of giving both prisoners and children a future, people who would easily become homeless, become my clients back home, if not supported and given purpose. I remembered giving tours at our resource center and at our housing site, and becoming insulted and angry inside when obviously wealthy people strolled through our facilities, smiling uncomfortably at the people they passed, and ending their tour with obvious relief, telling me the same line week after week, month after month, year after year: “God bless you for what you do.” All those years, I wanted to yell back at them, “‘God bless us everyone?’ For God’s sake, get down out of your Mercedes and HELP ME.”

I didn’t say it, but I meant it. We had relied on donations too, and grants that required applications and reports, quantifying people’s lives into tallied outcomes. Just to continue to receive small amounts of money to allow them the dignity of a bed, a shower, a cooked meal, and someone to talk to. All the things I received at the albergues.

The difference was, I was currently homeless by choice. True choice, as I had intentionally sold my house and saved money in the bank to pay my way. But the freedom of leaving the workweek/ weekend cycle of the full-time steady job came with a price. Guilt. I didn’t feel it all the time, but at moments like that, reminded of all the people who toss platitudes and run for the exit while you stay, every day – that’s when it would hit. My self-concept was built on the bedrock of “hard working.” Yet here I was, walking the Camino, every day a Sunday, every week a weekend.

I stuck to my resolve, to the statement I had made to everyone who offered possible part-time work options upon my return: “I can’t make a choice right now. Because I don’t know who I will be when I get back.”

I stuck to my resolve, to the statement I had made to everyone who offered possible part-time work options upon my return: “I can’t make a choice right now. Because I don’t know who I will be when I get back.”

I didn’t know why it was so important until I reached Guemes. But the part of me that was not a social worker, the reclaimed poet and artist and singer, needed time – a month of Sundays, as they say. At the very least. So I decided I was okay with just giving Father Ernesto my friend’s money that day, resisting the urge to tell anyone, sincerely, from one who knows – God bless you for the work you do. Because they were already blessed. You could feel it.

Instead of joining the work, during my day at Guemes I was fed my one-and-only albergue lunch of salad, soup, bread and wine; this prompted a nap in the sun. After writing in my notebook for hours, supper was pasta, more soup, more bread and wine, and a nectarine for dessert. We sat at a half-dozen long wooden tables in the low house that had been Ernesto’s home, meeting and greeting each other over food and drink with the conviviality of living outside the tyranny of time.

I sat by Danish Svend and his polite but slightly intimidating friend, as well as two Danish women. I asked the women about the Danish concept of hygge, plus how to correctly pronounce the word. It’s tricky, not so easy to get used to, softer than it appears – and the pronunciation is all those things, too.

Because hygge meant exactly what we were experiencing: being together in someone’s home, eating and drinking and enjoying each other, all without worry of time or responsibility. It was about closeness, friendliness, easy fun. Like when all the tables joined forces in teasing the Germans that they just HIKE! HIKE! HIKE! and don’t know how to have a good time, our uproarious laughter creating a running joke on the Camino for weeks to come.

As I left the next morning, Svend told me, “Barbara, we have learned that the way is more important than the pace – so we hike the slow Camino,” and smiled and shook my hand, thanking me for talking about my dawdling journey. Turned out, only Svend’s name was Danish – he and his friend were German!

Maybe my slow pace was catching on?

Who’s to say. Hygge Camino.

what is this sabbath

I have found

a singing walk

to a warm shower

clothes like flags

our countries flutter

from the line

and the bell calls

to practice

comraderie

over salad

with olives like surprises

commiseration

over soup

potato and chorizo

in tomato broth of

all our walking

communion

as our glasses clink

with the wine

of the joy

of rest

November 14, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I met Pablo at the Liendo albergue beside the church, where I had chosen a bottom bunk and he took the top, making sure I wanted the lower one. I joked about my terrible feet “so no ladder, please,” and he joked about his tired legs, and so we laughed together. I had seen him and his friend Juan Carlos in the albergues, but we had never met. Opposites but well matched, where Juan Carlos was lean, light-haired, with glasses and an eager smile, Pablo was massive, like a bull made man, with dark hair and an intensity to his sincerity that made you stop and really listen to what he was saying.

Pablo had decided he would use a chair to step up into the bunk, but the ridiculous young American had piled things on it – yes, the taverna orator slept at the foot of my bunk in a cot – so I set my pack by the chair beside my bed, to keep one available. I fell asleep early, but awoke to hear Pablo enter the darkened room and stop in front of the messy chair. He sighed, I’m sure not wanting to move someone’s belongings, but how to climb into bed?

I quietly said, “Pablo,” and he turned toward my voice. I patted the chair beside the bed, where he could not easily see.

“Thank you, Barbara,” he said, sounding quite pleased, and arranged items on his bunk as I snuggled into my sleeping bag. He said soft words in Spanish I did not recognize, then immediately translated them for me: “Sleep well, Barbara.”

I said, “You too,” my drowsiness especially cozy with this sweet wish for me.

He climbed into his bed later, and through the night I felt terrible as I realized my mistake. I hadn’t thought to give this huge man the lower bunk; as he carefully, carefully turned over, I understood that his entire weight was perched on a very flimsy platform, defying the laws of both gravity and poor construction, while my small self had the security of the sturdy lower bunk. Next time, I vowed.

In the morning, with no trace of resentment, he gave me two yogurts for breakfast, he and Juan Carlos offering “Buen Camino!” as they strode away. We kept meeting up here and there along the way, so that by the time I was standing in line on the beach for the Santoña ferry, I was not surprised to hear him call my name.

“I am not so sure about this boat,” he said, arriving behind me with Juan Carlos, and we all took turns pointing out laughable deficiencies in the aging ferry, jokingly convinced we were going to perish in the low-riding boat packed with pilgrims and tourists.

“At least we will die among friends,” I countered.

As we stood in line, and eventually boarded like sardines into a tin, and even over the roar of the ferry’s motor, Pablo asked me questions about my life, and I answered them, every one. By the time we got across the water, he wanted to keep in contact, and so we exchanged emails and phone numbers. He wanted to show me around Barcelona, where he lives, but he would be working in another city on the day of my flight layover in Barcelona, the day I would leave Spain.

I asked, “What work do you do?”

Pablo’s expression became quite serious, and I felt concerned as I waited for his reply: “I am a policeman, in Barcelona.” Then he looked into my eyes, waiting to see how I would respond.

“Oh good!” I blurted happily, other less pleasing possibilities dissolving from my mind. “A policeman! That’s wonderful! My father was state police. He taught me something important: he said, ‘You must enforce the spirit of the law, not the letter of the law.'”

“I agree,” Pablo offered, seeming relieved. And Juan Carlos? He was a cop, too. So I had been escorted more safely than I could possibly have known. For days now.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

At Playa Berria, between Santoña and Noja, the sand was like powder. Sunny skies and gentle waves beckoned like a sweet voice, so I stripped down to my underwear and tank top and walked into the surf. And just like that – for the first time in my life, I swam in the sea.

The water was cold until I got used to it, then…perfect. The waves bumped against me like a horse wanting to be scratched. They made me giggle and laugh like a little kid, and massaged my tired legs, the sand cradling my healing toes. When bigger waves came, my chest and then my face got wet. Salt. I tasted the sea. Delicious. Finally, I dove in while it was calm, and swam.

I eventually got out of the water and lay on my towel until I was dry, the sun not too hot, the breeze not too cool. I drowsed, thinking, I will remember this day at the beach all my life. As I drifted off into a nap, I saw again the shining turquoise water rolling over me, safe under the arc of the wave as if under a loving mother’s arm.

I woke to eat a lunch of quick snacks, realizing the afternoon was drifting by like the soft clouds above. I got dressed, packed up, and hiked up the beach to rejoin the Camino as it ascended a steep cliff on what looked like a goat path.

After several kilometers, I reached the Noja albergue to learn that I had played too long: the albergue was full. Completo is the letter of the law at the albergues. Finding the turismo, I was assured of a bed at a private albergue in Meruelo, another 6km away it turned out, after the classic reassurance regarding all distances on the Camino: “Just 2km.”

I arrived, with tired feet and sunburned legs, at 8pm, not my usual three-o-clock. But since it’s light until almost 10pm in Spain, no problemo. A community dinner of over a dozen peregrinos offered good food shared in a spirit of bonding comraderie; a shower, a comfy bed, and I fell asleep easily.

Missed a bed for swimming in the sea. Oh yes, I would most definitely do it again. Most delightedly so.

November 13, 2017 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

in every village

here I find

a church

with houses

clustered close

as if this god

would strike

them if

they scattered

I was getting smarter about my mileage. Kilometerage. I’d taken two stages (per my guidebook) and divided the total 60km into three days of 15-25km each, depending – longer days of flatter terrain, shorter days of mountainous terrain. It felt like my guidebook was written by this guy who wanted to check the Camino off his bucket list. His name was something like Alexander; I decided he was an Alex. When I needed more detail, Alex provided none; where Alex gave me details, they were often extraneous, as I looked up and found yellow arrows guiding me.

So I decided, That’s it, Alex – I’m taking my Camino into my own hands. Taking back my Camino power. Power to the Peregrinos! Oh Yes We Caminante! Watch out…troublemaker at the taverna; yeah, the one with the cafe con leche and big awkward notebook. El Gallito: the rowdy Rooster crows.

I was walking stronger these days, better in my boots, slightly faster pace, and as I grew stronger, I felt younger. And as I felt younger, sometimes things got interesting.

As I sat drinking my coffee, I couldn’t help overhearing the loud, young American at the next table pontificating to his new European friends. First, he defended recent spectacularly failed military decisions by our most inexperienced and incompetent president; I felt my jaw tense in embarrassment, like I was silently taking it on the chin, but sipped and tried to continue writing. But once he said, “Americans – we love our guns. We have great gun policies” – inside, I lost it. That’s it, Alex.

“Speak for yourself, friend,” I called over, the disgust obvious in my voice.

“What was that?” he asked, startled at having his monologue interrupted by a heckler.

“Speak – for – yourself,” I repeated. “Speak for yourself, not for America. Don’t speak for me. Some of us think our gun policies are terrible.”

“Are you American?” he asked, bewildered.

“Yes, and for much longer than you,” I replied condescendingly, holding back the “sonny” I so wanted to add to the end of that statement.

The Europeans were clearly entertained, as the young American tried to save face. “I was just speaking in generalities,” he backpeddled. But I wasn’t having it.

“You can’t do that. You have to speak for yourself. Just give your own thoughts standing on your own two feet – which is harder,” I added pointedly. “Don’t speak for me. I can do that just fine.”

We agreed to disagree, meaning he said he would stop talking about guns, then left for the bathroom. Seventeen-year-old me sat back, satisfied, and finished her coffee. Sonny, she mused into her cup.

Age had tamed my fury but not my tongue. Still, I was reassured no one had assumed I was American until I made that fact clear. I was trying to just be myself, not represent a superpower. The “Ugly American” reputation abroad was not unfounded, and I had been trying to steer clear.

All along the Camino, it kept happening: I was most often mistaken for British, or Danish, which actually made sense. Only third-generation American, I grew up among Nordic elders new to the country, and the language. My Midwestern accent had never faded, even after I moved west, and so I spoke English with the inflection of that farm country filled with Scandinavians, but slowed to the pace of Colorado ski bums. I sounded like a Dane who spoke English as a second language…or a tired Iowa church lady after a long morning serving coffeecake in the church basement to my sewing circle. As a child, I assumed all old people spoke with Norse accents – simply as a function of age, as if I would also adopt this speech pattern one day. Maybe I had.

I’d been studying the Primitivo route in the guidebook again. While the Norte took me along the seaside cliffs and down onto the warm sandy beaches, the Primitivo crossed the heart of the rugged Asturias region, mountains said to make my day out of Irun look like child’s play. Soon I would come to this fork in the road, Norte versus Primitivo. I remembered my cab driver’s warning: montañas. I had disregarded it to my blistered feet’s regret. Yet I carried an irrational belief that my Rocky Mountain hiking would somehow see me through the high-altitude Primitivo, all appearances on the Norte to the contrary. Besides, I had a walking stick now.

I felt a longing to see this oldest stretch of the Camino, some of it said to be from the 700-800’s, traversing Roman roads and bridges. I struggled to conceptualize this ancient history under my feet, and wanted to walk it myself, place my feet into the dusty footsteps of so many thousands of pilgrims before me, century upon century. I wanted to join them.

I felt a longing to see this oldest stretch of the Camino, some of it said to be from the 700-800’s, traversing Roman roads and bridges. I struggled to conceptualize this ancient history under my feet, and wanted to walk it myself, place my feet into the dusty footsteps of so many thousands of pilgrims before me, century upon century. I wanted to join them.

During the eighth and ninth centuries, my own people would have been in full-on Viking mode, invading Britain, creating the Danelaw, eyeing France and the riches of the Mediterranean. Not particularly penitent. No church could yet hold their allegiance. They answered to wild gods who bestowed honor upon those who died in battle.

I felt relatively young, my life next to all this history, as I considered my blisters and cracked stick against the Primitivo – and a bit foolhardy. As young people often are. As my recent ancestors had been, to leave home and family for America. Risk takers. Adventurers. Audacious.

You probably shouldn’t speak for them, though; you don’t actually know what they went through, seventeen-year-old me mocked.