Bandelier or Tsankawi

If you go to Bandelier National Monument at sunrise, you arrive to absolute stillness, walking alone through the remains of the dwellings of the Ancestral Pueblo people, letting the silence surround you.

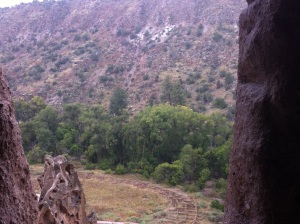

It rained briefly. I sheltered inside a cave used hundreds, even thousands of years ago, by ancient people now long gone. Looking out from the same entrance across the remnants of stone walls, watching the rain slant between the canyon cliffs in the gray light, time seems to pause, bend, and swirl about you.

I’m retracing my steps, as I’m retracing their steps. Twenty years ago, I walked these same paths, looked into these same caves, gazed out over these same walls. Arrayed in a sweeping circle in the narrow valley of Frijoles Canyon, I feel myself circling over them like yet another spirit from long ago.

what shall we use

to fill the empty spaces

where we used to talk

how shall I fill the final places

how should I complete the wall— Pink Floyd, “Empty Spaces”

It was here, at Bandelier, that I first began to realize how walls come to be built: for safety. Trying to keep things safe, we put ourselves and all that matters to us into boxes. Nothing new; I stood looking at a similar attempt created over 600 years ago, Tyuonyi Pueblo. Tyuonyi is thought to mean the place where a significant treaty or agreement was reached, a council site; it was also a home, to about 100 people.

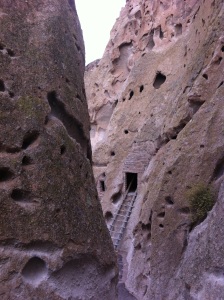

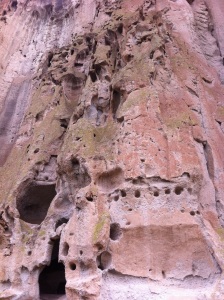

Some made their rooms within the canyon walls, finding caves that they expanded, then walled in, with ladders to reach them.

These were the Anasazi, now known as the Ancestral Pueblo; Anasazi is actually a non-Pueblo word meaning “ancient enemies.” It’s unclear why they migrated from the Mesa Verde area to this canyon, and from here, farther south again. Theories include drought, inter-tribal warfare, over-population for available resources, but we don’t really know. What seems clear to me is that each placed they settled into, they thought would last…like their council, and their treaty, and their homes in the stone. But the stone is soft. And the people didn’t stay.

Nothing is built on stone; all is built on sand, but we must build as if the sand were stone. — Jorge Luis Borges

My mind drifts back in time. I came here then trying to mortar the crumbling walls of a home that would not last. I remember intense heat in mid-summer, crowds of people talking, my baby daughter in her little sunhat asleep in the backpack. Now a cool breeze whispers at my cheek; when I turn to look, the memory ripples and disappears.

Memory is the fickle partner of Time, not always reliable, or honest. It shapes itself, giving itself airs of importance, prestige, dramatic meaning. Memory also has a way of evading self-reflection and of blunting sharper edges sometimes, especially regarding the recollector. It is not an accurate historian.

But apart from their skewed narrative settings, remembered images often capture the emotional essence of an experience. Their photographic quality can be powerful for the color and intensity of the feelings associated with the moment. But like dreams, as we try to hold onto the impermanent images themselves, they dissipate, dissolving into the present.

We shape our dwellings, and afterwards, our dwellings shape us.

— Winston Churchill

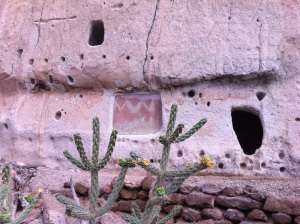

It’s easy to see the ways people here tried to create a sense of home and permanence. Rows of holes show where porch posts and balcony floors were secured into the rock. Natural pigments created painted patterns on walls, and carved images feel familiar somehow. It isn’t hard to imagine children ducking through these cave entrances and running from one doorway to another between stone walls.

Now the people of this pueblo are gone, voices in the winds of the past. But so am I, so is the younger me who came here in the heat of summer. The dwellings they created have a place in my personal history, and so in shaping my life.

Yet the river of time keeps flowing. The baby is a woman, living in the city, taking the train to work, laughing with friends over coffee. Her laughter waivers in the air around me as I start my jeep and drive on to Tsankawi.

In dwelling, live close to the ground.

— Lao Tzu

While Tyuonyi means a council place, Tsankawi simply gives directions to itself: “village between two canyons at the clump of sharp, round cactus.” I like this meaning; it’s unpretentious. And at Tsankawi, they did live close to the ground. The white stone of the clifftop wore away under generations of bare feet following the same trails, so that now, stone grooves knee-deep to chest-deep in places attest to the interaction of people and earth in a different way than Tyuonyi: here, humans impacted the earth more like water does, wearing away the rock over hundreds of years just by following the flowing course of their daily lives.

I feel more grounded here. This was the area I had sought to find when I came to New Mexico decades ago, and it lifts my spirits again, this open community on the Parajito Plateau, the breeze from the returning rain ruffling my hair. This was an inviting place to live, centuries ago. Even though people here still used caves in the cliffs, still stacked stone walls to create store rooms, somehow the essence here is open, wide open. “Parajito” is “little bird,” and I see them everywhere, flitting among the brush, lifting and swirling in unison on the rising wind, winging away to wherever they wish to go.

I think it’s the forthright exposure of human presence, vulnerable here on the edge between the two canyons, that pleases my heart. Unlike Tyuonyi, there’s really nowhere to hide. With no intention to hide.

I think it’s the forthright exposure of human presence, vulnerable here on the edge between the two canyons, that pleases my heart. Unlike Tyuonyi, there’s really nowhere to hide. With no intention to hide.

The name tells you exactly where to find the people, how to get home, with no glamorizing story, no muting the canyon winds, no softening of the clump of sharp, round cactus.

I’d rather be at Tsankawi. Let’s give directions to ourselves, that we may be found, and understood, by the people we love. Let’s be at home in ourselves, sinking deep into a grounding that is at once both solid and open. Let those we love become los parajitos, the little birds who are lifted above us and able to become whomever they choose, flying wherever they wish to go. Let us walk along the canyon edges and be free.

What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.

— Pericles