September 8, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

“Kindergarten on Zoom?!” I watch my grandkids pinballing around the living room. “Let’s find Mr. Rogers online.”

As the opening song twinkles up the xylophone, three little heads turn in unison, then sit, as if hypnotized. The one-year-old sucks her pacifier intently.

“Would you like to see what I’ve brought?” Mr. Rogers asks engagingly.

“Yes!” answers the three-year-old. The kindergartener is curious, too, ignoring the game on the iPad in his lap.

My daughter is delighted, and so relieved, even if only for five minutes.

Mr. Rogers is the kind of grandparent I aspire to be. Only problem is, I’m not the kind of person Mr. Rogers is on his show. He offers infinite patience. He always has time for children’s interests and concerns. But Mr. Rogers, how game would you be to play nonstop superheroes fighting bad guys? To engage with neverending dragon battles on a tiny screen? I’m Captain America one minute, Saint George the next. Or maybe I’m the dragon.

I’m so tired of fighting. This has been a very long year. One of many, in a long life now.

Each generation fights to be seen and heard, to feel like they have some kind of power. And each generation worries about the worldview of their children, afraid they haven’t taught them well enough. Haven’t taught them to see, or to listen. We all think: you can’t continue to fight fire with fire. Guns or flames, we’re all going down, this way. And then we all think: I can’t stop this, this is the way of the world.

Mr. Rogers has brought two suitcases with him into his house in The Neighborhood. He says they are for going on trips — but not to worry, he isn’t leaving. He reassures us he isn’t going anywhere. Instead, he explains he’s brought things to show us. He opens the old silver latches on the small suitcase to reveal: it is packed full of small hats. Doll hats. Puppet hats. Many hats that cannot fit on any real people, no matter how young, no matter how small.

I look at the kids. They are enthralled. By an old suitcase full of tiny hats. All thoughts of fighting have ceased. They are engrossed in their own curiosity.

These unexpected little hats have slipped past their habits and expectations. You can physically see the wonder, the questions forming, the engagement with possibilities yet unknown. Mr. Rogers asks, “Would you like me to show you what’s in the big suitcase?” They all lean forward in anticipation.

The world is bigger than we are, tiny people. So much awaits us, to be discovered.

All you heroes and dragonslayers, it’s okay to lay down your weapons for a moment, take off your sweaty helmets, and rest from your weary labors. Mr. Rogers is about to open the silver latches, his wisdom found in his gentle understanding: we all want to see and understand what is inside. He knew we need a quiet space to explore what we find. A safe space. Kindness.

August 11, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

IN THE PALM OF MY HAND

circling and circling, yet not quite

spiraling out of control

but wasn’t that

the point? the idea

to relinquish

control? the illusion

that choosing is done

with my mind

it is

done

by doing

I didn’t realize everyone could hear the sound of the heavy vault door slamming inside my mind. But of course, they can. They hear the echo of such solid finality, feel it reverberating through the air around me as I walk by, the shockwaves still registering underfoot, rolling through the Earth’s crust with exactly the rhythm of the waves of a sea change. The rhythm of my footsteps walking away.

I have decided. To go.

I didn’t intend to, if I’m honest. I thought I could stick around longer this time, here in this cushy job, good pay, free benefits. My cheap, so cheap New Mexico apartment, the warm adobe row of small weathered doors circled around a green courtyard, inside full of windows and charm. I thought I could sink in, be lazy for a while, lie low in the Land of Mañana.

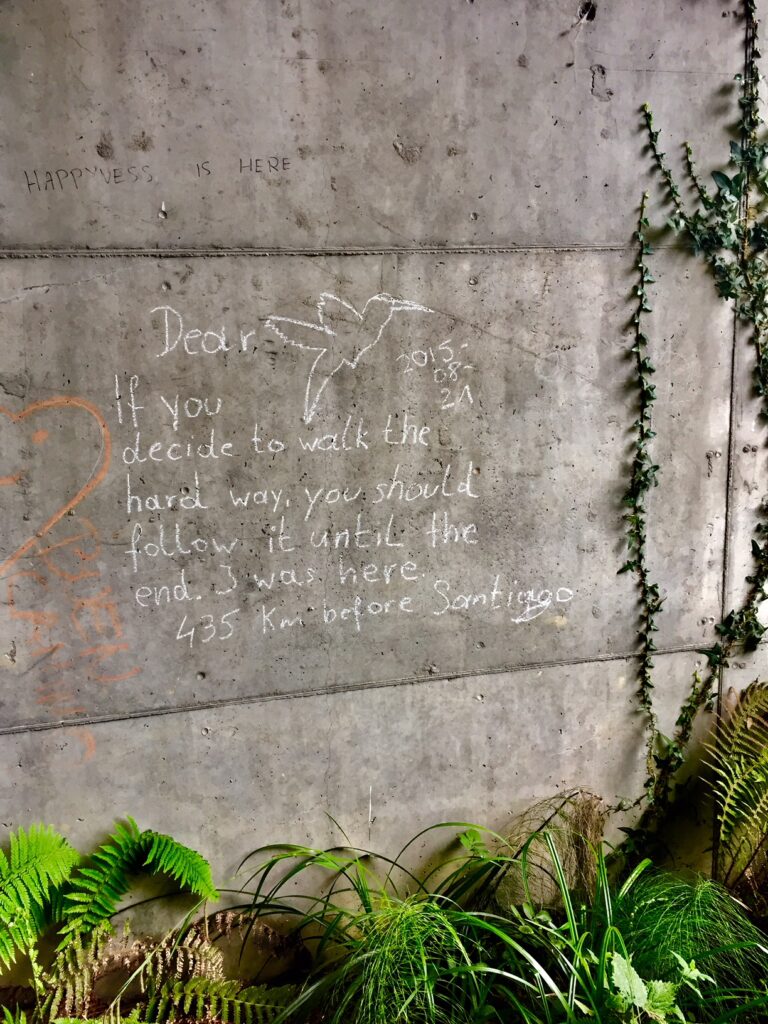

But the Wind through the pine tree at the corner of my front porch calls to me, whispers my true name; it traveled all this way, from the mountains of Colorado, along the Camino in Spain, to find me here. It tells me its brother, El Derecho, just tore straight across the cornfields of my childhood at 100 mph, screaming like a freight train, like a tornado unwound, a line drive through center field, obliterating anything that stood in his way.

The old trees are uprooted, broken, says the Wind. Their solid persistence to stay in their place — that was their undoing. You slammed the heavy door in your mind; and that Butterfly Effect unleashed him, the wild wind, to free you. You look for your straight arrows to guide you:

El Derecho is pointing the way.

The Sun set, rosy clouds in a lavender sky, and took the Wind on along as a companion, leaving me leaning against the corner of my porch, looking west in the dimming light.

I have been trying so hard to persist here. Why?

All these years later, I still struggle to let go of the steady paycheck in order to grab hold of my adventurous life.

Two symbols have risen before me of late, each more than once, insistent, using others to remind me when I’ve tried to ignore them. The symbols glow within the palms of each of my hands – in one, a spiral; in the other, an eye.

A hand with a spiral in the palm is the Shaman’s Hand, or Healer’s Hand. Native Americans in the desert Southwest, in particular the Hopi, have a long relationship to this symbol. It is a sign of spiritual connection, healing creativity, and protection.

A hand with an eye in the palm is the Hamsa, or Hand of God. In Islam, it is also called the Hand of Fatima, the devoted daughter of the prophet Mohammed, and in Judaism, the Hand of Miriam, the sister who placed baby Moses into the Nile River to save him. Across the Middle East, this symbol guards us and our loved ones from the “evil eye” – so it, too, is a sign of protection.

So much protection surrounding one so insulated by ease and comfort. I’m growing fat and soft, uncomfortable in my own overabundant skin, impatient and uneasy in the midst of my monotonous plenty. To what end? To what end do I continue this job, this lifestyle, except to the end of me?

It’s not that the agency where I work has changed. Nothing has changed. A pandemic has torn across the world like El Derecho, direct and destructive, and still, nothing has changed. I believed I was hired specifically to bring vision and change, but that was lip service, a backhanded request to clean up the indulgent disaster of their own making. What remained unspoken was the desire to then go back to the way things have always been. The Land of Ayer. Yesterday.

This new arrow in the wind reminds me: once you have left, there is no going back. Maybe I didn’t explain that clearly enough to them. Or to myself.

This evening, I found a short essay from 2015 published in Ploughshares about the Japanese writer Yasunari Kawabata, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968. Incredibly, three months before his death in 1972, he reworked his prize-winning novel into a small 11-page story. Essayist Lara Palmquist wrote in “Pursuing Essence Through Ambiguity”:

“…[W]hile the story pulls scenes almost intact from the novel, it does not offer a condensed retelling. Rather in his distinctly spare yet affecting style, Kawabata’s miniaturization intensifies the isolated images, producing an independent take on his regarded masterpiece. In excavating new facets of his novel, Kawabata was also returning to the form he felt encapsulated his art: a series of short works he eloquently described as ‘palm-of-the-hand stories.’”

“Palm-of-the-hand stories.” I’ve often referred to my best writings as small vignettes, photographs. Or sometimes, song lyrics. Palmquist went on to explain,

This is the uncanny magic of Kawabata’s form: a deceptively small structure with limitless…capacity. It is precisely their ambiguity that invests the palm-of-the-hand stories with deeper meaning, their irresolution that exquisitely reflects the near-infinite, interior epics of life.

Half my lifetime ago, I sat in a studio apartment among my most beloved poets, all of us young and poor, as we each wrote from a shared prompt, creating a project together. My heart was full that afternoon, even as it felt spacious and free:

I found a rock I picked it up I put it in my pocket for a day

a piece of solid life without a breath it once grew corn it once was clay

and on its jagged edge I felt my thumb I learned the texture of my skin

and when I smelled the dust of it I tasted it and flew the sky within

and oh, I play hopscotch on the ordered plans of man

I sweetly sing visions in this unpromised land

the answers to the mysteries are etched on our hands

I’m laughing walking on the shifting sands

and who can know the weight of snow

unless he walks outside his door

and feels the weight of white

and feels the weight of light

I am a woman day I am a (k)night in shining blood I will give birth

to visionaries souls without a mark and madmen restless on the earth

and all your laws and all your jails will not prevail against the human curse

the misery of clarity may drive a man to tell the truth or worse

and oh, I play hopscotch on the ordered plans of man

I sweetly sing visions in this unpromised land

the answers to the mysteries are etched on our hands

I’m laughing walking on the shifting sands

“Where did that come from?!” Ted had asked me.

I looked at his amazed face, then back at the notepad in my hands, and shrugged. “From writing about…’white’…the prompt? right?”

The other poets praised parts and commented and then discussed the larger project. Ted leaned back on the futon and said quietly, “Sing it again.”

Some Muslims believe there exists an hour within the day on Friday when God answers all prayers. It is called the Hour of Fatima – the one hour before sundown. When the wind whispers through the pine trees, and calls you by your true name as it searches for you, high and low, bringing you a message you need to hear. Like voices from the next room in the albergue in Spain, hushing, “Shhh – Barbara is singing.” Asking me if I would be staying with them the next night, and singing them to sleep.

It’s not about pursuing songwriting as my next career move. I don’t know what my next career move is. I just know I need to listen to these voices, including my own. Kawabata calls to me on the wind, leaning back and saying quietly,

“Put your soul in the palm of my hand for me to look at, like a crystal jewel. I’ll sketch it in words.”

My sentiments toward the world, exactly. Who can know the weight, the value, of anything we encounter or hold, unless we step outside our old worlds, and into ourselves.

Shhh – the wind is singing. I have decided to follow it, across the shifting sands.

August 4, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I am Wednesday, full of woe. My brother Sunday’s all bonny and blithe, good and gay. He calls me “Emo;” I call him “Pollyanna.” I used to be Woden’s Day, honoring Odin, the Norse god seeking wisdom. Then Judas decides to betray Jesus on a Wednesday. Now my claim to fame is hump day and coupon flyers in your mailbox. Sunday, smugly home from church, eats his chicken dinner and watches college football.

Sure, crucifixion, resurrection. I mean, my namesake lost an eye, threw himself on his spear, and hung on the Tree of Life for nine days and nine nights, all to gain knowledge and understanding. He cured the sick, calmed storms, just like Jesus, I’d like to point out. Jesus was god, Odin was god. The One-Eyed All-Father, an impressive title. Jesus has a kingdom; Odin has a kingdom hall, too – ever heard of a little place called Valhalla?

Angels or Valkyries, the faithful return, whether saints or warriors. So what is the deal? Why does Sunday get EVERYTHING and I can’t catch a break? Home-cooked fried chicken every week versus $2 Whopper Wednesdays. Come on.

Woe. Oy vey. Which in fact is part of the problem here – all these “woe” words are natural exclamations of lament by humans around the world: Old English wǣ; Middle English wo, wei, wa; Dutch wee, German weh, Danish ve, Yiddish vey. Bosnian jao, said, “yow.” Portugese ai, said, “aye,” as in aye-yi-yi.

Wednesday, Kuan Yin, Avalokiteshvara. I’m tired of being “She Who Hears the Cries of the World.” I feel like I need to update my image, rebrand, quit reliving the glory days of Odin’s quest for wisdom. The serpent Jormungandr is shaking the world now; Yggdrasil is groaning heavily in the uproar. We seem to be approaching a burning, drowning, come-to-Jesus moment for the Earth.

I’m not going to bring it up, though. I don’t want to give Sunday the satisfaction.

Think I’ll go with the tagline “fee, fi, fo, fum.” That’s Shakespeare, from King Lear. True, it was said by a double-crossed royal prince framed for murdering his father the king now hiding out pretending to be a village madman. But that’s way different than “woe,” right?

Fee, fi, fo, fum. Giant’s Day. Shorten it to Ginday. Card games, chilled drinks, a PROFESSIONAL football team. The living is easy, here at the end of the world.

So much cooler than Sunday.

July 23, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Here’s how I have to approach you: I have to circle back around. Like livestock that got out through a broken fence, I have to calmly gather you back in to what I’m saying. Getting mad won’t help. I tell you my latest idea, and you immediately bring up the other side of the argument. As if I’m both a curmudgeon and an idiot, now that I’m fifty-four. As if I’ve never gathered hogs. As if I need you to show me that other people have other intentions. Other approaches.

You quickly tell me about an amazing essay you read, by someone closer to your own age. I listen carefully — then get to just as carefully use your story as an example of exactly what I just told you. Now, with your peer’s frame of reference, now you can begin to hear me. Now I’m not old and bitter and judgmental. Now it becomes possible that I’m just noticing. Like the amazing essay author.

My point became lost as I tried to put it into words. Farm references don’t always translate well to urban issues. More than that, words struggle to bridge generations. They always have. How many times, I wonder now, did my dad, my grandpa and grandma, my uncle with his wry, witty reflections — how many times did they try to tell me some very simple observation about life, and I hurled their small pearl of wisdom into the hog lot like a rotten apple?

Intelligence is not wisdom. I’m on a bridge between these two shores, without a foot touching either side at the moment. It’s raining, here in midlife, a sudden downpour that tried to warn me by sprinkling little showers here and there as I attended to the tasks at hand, thunder rumbling like a scolding. This bridge stretches between the heavy smell of wet hogs fenced in their pens and the warmth of Grandma and Grandpa’s farmhouse. I’m walking the sloppy gravel drive to get there, hair plastered to my head, my chore boots a mess of wet manure and mud, but the sheltered metal porch chairs sit welcoming and familiar, a safe place to pull those boots off, peel off dirty, soggy socks, and wipe my dripping face with my wet sleeve, fingers finally slicking my hair back from my eyes. How many times did I wait on that porch in the rain, noticing, as if I alone could witness such a storm.

I remember the quicksilver brilliance of my youth, concepts and decisions flashing like a mathematician’s chalk on a blackboard, like a musician’s improvisation, like a poet’s voice, the microphone close and seductive, my lips spinning everyone into the dark room with me.

I miss a step now and then, here on the bridge. I feel it, sometimes clumsily, like I’ve stubbed a toe, or sometimes like I’ve caught myself just in time from landing on a rolled ankle gone soft right when I needed its strength. And sometimes, I still feel the foot that for whatever reason didn’t come as far forward as I meant it to, dragged itself ever so slightly, still lingering just behind my intention.

I wonder about Parkinson’s. I think of my grandma’s congestive heart failure. I make my uncle’s doubtful expression at the memory of anesthesia, surgery to save my life burning the bridge behind me, no way back to brilliant now. I have my mother’s tremor in my right hand. I have my dad’s creaky ankle that burns and aches if I drive too long, his lower back that is corkscrewed into wide, flat hips. I think I’m my own person, when even my smile is a blend of the two, her smile on top, his below. Every bit of my uniqueness is built of hand-me-down gifts.

You’re so young, so brilliant, so sure. Yet I wish again, for the hundredth, for the thousandth, for the millionth time, that I could bring you inside my heart and mind, help you see what I see. Convince you that I notice, and I care, deeply. That my words that so irritate you are the gritty, sandy seeds of your own growth. That everything you think you need to teach me to see, I taught you to see.

I wish I could tell you about life without you subtly correcting me. The ones fit for that task have long since crossed the bridge and traveled away. I am more familiar with this bridge than you are, have stumbled along more of it, have been walking in the rain so much longer than you have yet even been alive. Before I get too far along the way, let me circle back, and place these few small pearls in the palm of your hand. There aren’t many, but they’re all I have to give you.

Do with them what you will.

July 14, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

First, I thought they were hummingbirds. Barrel-shaped bodies flitted among yellow-dusted blossoms hanging under lacy leaves. From my desk at the window, I watched them swoop on buzzing wings through the slender locust tree growing between the sidewalk and street. I imagined hanging a red nectar-filled feeder by my back door. But it’s all adobe, my back wall; there’s nothing to hang a feeder on. And they weren’t hummingbirds.

Then I thought they were cicadas. I saw one that was a coppery-brown, another darker, and since I have only known cicadas by their heat-gnawing summer song and husks of abandoned skins left clawed into tree trunks and branches, I guessed they might fly in looping arcs if given the chance.

However, it appears they are a type of huge bee, built like a bumble bee but without the bad temper of that chubby garden tyrant. Carpenter bees, who chew a perfectly circular hole into any unpainted, untreated wood to make a nest. I read that the males can be aggressive when protecting the nests; yet even if they dive-bomb, they’ve got no stinger, so what do they do? Head butt? Body slam? The females have the stingers, but it seems they rarely use them. Females prefer to stay in their wood tunnel burrows. You have to provoke a female carpenter bee to get stung.

I keep encountering how much I don’t know. Like the last time I went running at the volcanoes. I saw a very looonnngg baby rattler stretched halfway into the trail, which, upon second look, I thought probably wasn’t actually a baby rattler. This snake’s head was shaped differently, and the body seemed to shine with a coppery stripe, though toward sunset, who can know what they’re really seeing. The thing is, this snake looked fast. I can’t explain this to you, except that upon seeing this very looonnngg baby rattler, entirely unmoving, unblinking, I just knew. This makes no sense, I realize, and I’m with you in being annoyed that I would state as fact what I clearly don’t know.

But life is like that.

Striped whipsnake. Belonging to the snake family of “racers,” colubridae, they’re incredibly fast: fast as a whip. They typically grow to four feet long, hence their nickname “coachwhip” (think stagecoach). Whipsnakes are often found draped in bushes like tiny anacondas, or heads-up on the ground, their faces little periscopes above the cactus as they glide across the desert sand, searching for something to eat.

Whipsnakes are generally nonvenomous. Also not constrictors. They are typically harmless to humans, though a bite still wouldn’t feel good. Nevertheless, their prey includes lizards, frogs and toads, ground-nesting birds and small mammals, even other snakes – including rattlesnakes. So how do they attack? They just rush their prey and eat it ALIVE. They. Eat. Rattlesnakes. Alive.

Appearances can be deceiving.

I remembered the carpenter bee and the whipsnake as I drove out of Albuquerque this weekend to escape daily temperatures of 105 degrees. I am not native fauna. A Colorado transplant, I realized the enormity of my error last summer; now, as July has unfortunately arrived again, I have forsaken my cool, dark cave of lethargic exhaustion in an attempt to escape. I am a mountain ground squirrel running frantically up the highway, hoping to find my habitat before my feet melt into the black pavement or I am crushed by the stampede of traffic behind me.

Against my usual prerogatives, I’m heading to Santa Fe. My hiking guidebook tells me I will find Nambé Lake at 12,000 feet. My flushed face and sweating body tell me I will find cool air and cold water within the high cirque holding this precious source of the Rio Nambé.

My bias against Santa Fe stems from its faux-adobe-suburban vibe, a city of seemingly over-educated, overly-thin white people who epitomize one stereotype of Santa Fe, salt-and-pepper haired arts patrons dressed in quick-dry shorts and web-strapped sandals, sunhats and sleeveless T-shirts baring old, brown arms, silver rings on several fingers.

People who look uncomfortably similar to me. I notice my hiking wear with dismay, driving in my Tevas with their red-patterned straps. My rings flash atop the steering wheel.

I haven’t explored much up around Santa Fe. I’ve been to Chimayo and Española, Taos and the Rio Grande River Gorge. I stayed at Upaya Zen Center for a weekend. I’ve driven up and over the High Road multiple times. But of Santa Fe itself, I only know the plaza. I only know the roads that leave Santa Fe. I haven’t actually tried to enter and explore the mountains that hold this city.

As its name suggests, Paseo de Peralta lifts you up into the hills. This road winds until it reaches another, and another, until you find yourself on Hyde Park Road. I associate Hyde Park with rich people back East, and as I drive past custom fauxdobe homes, my heart simultaneously sinks and rises with the road.

These hillside homes are, in fact, beautiful. The walls act as mere frames for windows that showcase the surrounding views, vistas that stretch and relax for miles and miles of high chaparral and wide sky. Hyde Park Road, and Gonzales Road that led up to it, cling to the edges and pinnacles of ridges, one of my favorite features of New Mexico roadways. The air is already ten degrees cooler. I drive past several neighborhoods of condos and realize I’m scouting locations for my life, smiling at the northern New Mexico Territorial architectural style with which I have always been taken, stucco and protruding vigas and shady porticos and little walled plazas for yards, sprouting sage and wildflowers. I like it up here.

You drive to the end of Hyde Park Road to get to the trailhead. I pass Hyde Memorial State Park, 350 acres donated by a member of the Hyde family in 1938, New Mexico’s first state park. “Hyde Park Road” takes on a different tone, after that.

The road wraps the mountains, curving its way up and up, through tight canyons and into taller forests. Guardrails along sheer drops feel familiar. Mount Baldy to my left reminds me that New Mexico does have peaks that rise above treeline. The sight of its smooth pate refreshes my eyes and gives me hope for this hike.

I arrive at the end of the road, a large parking lot for the Santa Fe Ski Area, and find a small gap along the side to park. I can see the trailhead sign from my car – as well as dozens and dozens of cars and hikers and lounging RVers and young Instagrammers in stretchy “athleisure.” The place is swollen with hot, sweaty humanity. But I don’t care.

Because I have reached 10,000 feet above sea level. And even though the trail begins with a precipitous rise that finds me huffing and puffing, I am totally at ease being this out of shape, this high in the world. Ten thousand feet never felt so good. My legs strain against gravity and against a summer so hot it has left me sedentary and depressed until now.

As soon as I reach the initial point of exhaustion, stopping at a switchback, feeling my blood and breath pulsing hard, my familiar comrades join me: the butterflies.

A speckled pair of bright orange, summertime energy swirl around each other and soon around me, one alighting briefly on the top of my walking stick, the other on the knot of the extra shirt tied around my waist. I feel energized with delight and relief to meet up with them, my trail guides of longstanding mutual agreement.

As quickly as they greet me, they lift and spiral away over the wildflowers. And just as easily, my temporary exhaustion is alleviated by joy. As I squeeze through the V-stile log gate into the Pecos Wilderness, I feel that my butterfly friends have welcomed me home. I follow their lead, wandering off on side loops, retracing my way back, crisscrossing the drainage, stopping to admire the paintbrush and columbine.

Even as I take yet another water break, for the entire six hours I am on the trail, I never once think this hike is a mistake.

Listening to the running stream and birdsong, I do think I might have been wrong about Santa Fe, though.

July 9, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Turquoise. How could I know? The ocean rolls waves over the surface above me, a landlocked desert pilgrim on Camino, the path leading to sand and sea. Weightless, swaying with the water, I relinquish my brokenness to wonder. Fragments of shell, tumbled by waves against hidden stones, emerge with me upon the beach.

I have dreamed of the turquoise water again. I believe it is the water that calls to me while I turn and float in sleep. But the water is only the voice.

The unexpected color of the light, curling waves reflecting my own eyes to me – this is the soul messenger, the fantastic angel holding my wings for me, again, summoning me to put them on, again, and rejoin the larger world. Come, swim out into the ocean, says Wonder. Wings become fins, fins become feet, feet take to trails, trails take to stars.

I am dried out, parched under this sun of relentless

knowing. What I know is small, scuttles under rocks for shade, waiting for the desert air to cool. With nightfall, the Mystery closes my eyes and draws me forward, winding and finding my way by flicking my tongue, testing my thoughts for the faintest scent of life. Hungry, hunting for new experiences that can feed me. By day, I curl into my den, dulled by heat, waiting.

I don’t want to know. I want to find.

Wonder as I wander, under the sky.

June 23, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

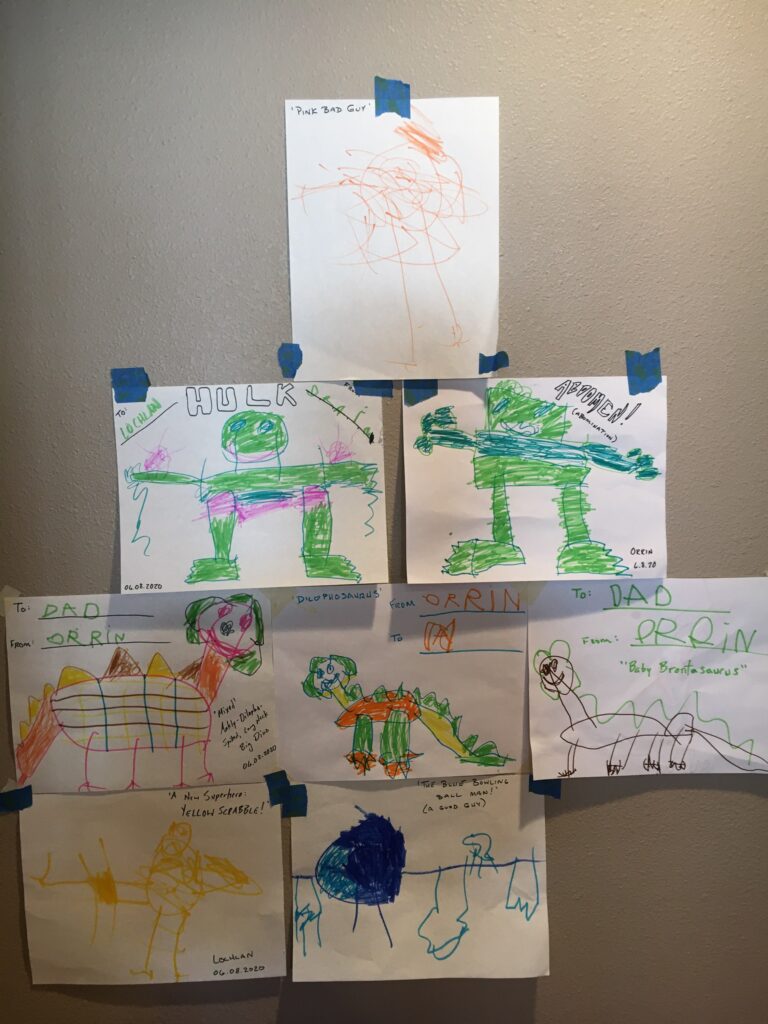

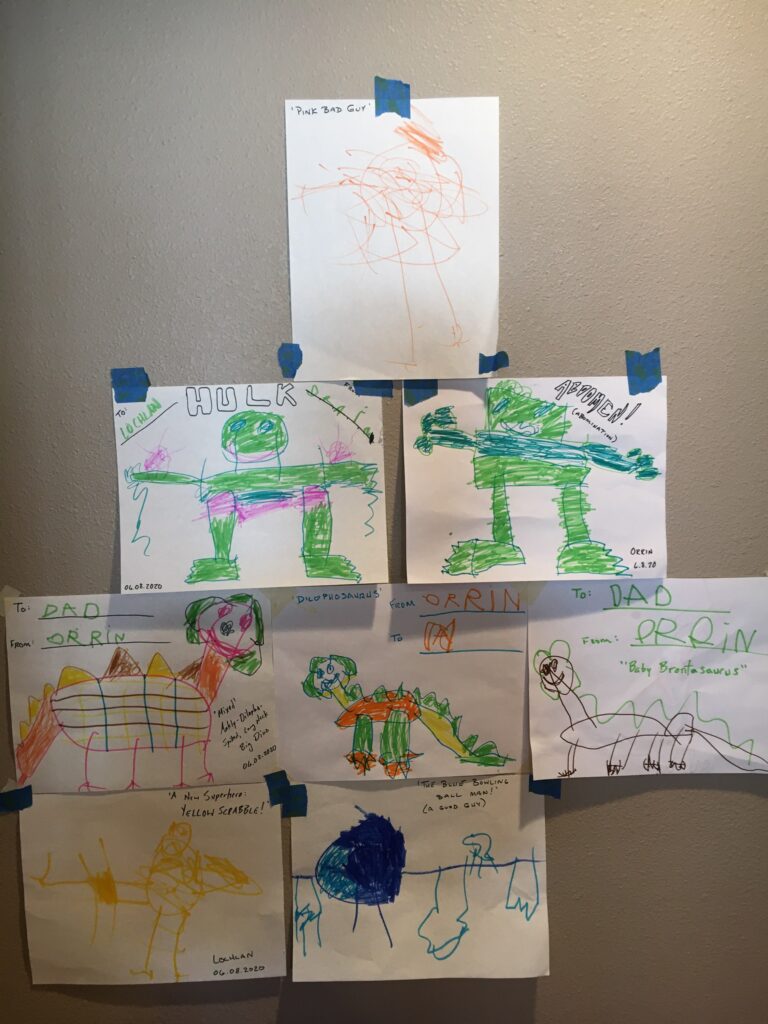

I learn so much from my grandkids. This month’s wisdom teaching comes from the three-year-old, explaining the role of superheroes.

Drawing a line of tall figures with round, staring eyes, he explained, “These are ghosts….” The ghosts are drawn in dark hues of purple, blue, and black. Their unformed faces feel vague and detached. Their bodies without limbs stretch like heavy robes to the ground, solid and imposing.

Ghosts. I think of all the images and stories we allow to haunt us, not only from fiction, but from our own histories. We can be tormented by unsettling visions from our past lives – especially our very-recent-past lives. Even from what is happening right in front of us, right now.

“These are ghosts that scare people,” my grandson said, confirming what I know to be all too true. “But they don’t scare Bruce Banner, because he saves people.”

Ah, the hero.

My grandson loves this particular superhero – not just The Hulk. He loves Bruce Banner. The ordinary guy who becomes something more than he is, on occasion. Through outrage at what he sees happening before him.

Even if your whole goal is simply to help people’s lives suck less, that’s so much more than a lot of people are offering. If the ghosts are our fears, our regrets, or what we become when we succumb to hopelessness, then Hulk might be a reminder of the double edges of being a superhero. It’s the injustices of bullying and exploiting and defeating ordinary people – the situations that create ghosts – that bring on Hulk’s roar. The price: you often feel like just smash, smash, smashing things.

The one who actually saves people is Bruce Banner. Because, using his great scientific mind and huge heart, he learns to tame and manage The Hulk. While Hulk’s superpowers are strength and endurance, Bruce Banner’s superpower is compassion. For himself, for his least nuanced and most aggravated reactions. For his primitive, irrational chest-thumping. For going green with rage and frustration.

Bruce Banner just keeps working at it.

My grandson drew some sidekicks for The Hulk. He made “Yellow Scrabble,” whose superpower I have decided is decimating wordplay, leaving a bad guy speechless with a triple-word-score comeback to his irritating remark, the superpower we all dream of. And “Blue Bowling Ball Man,” who, tiptoeing like a ballerina and then kicking that leg back with a flourish worthy of Fred Astaire, uses his weekend nonchalance in blatantly unattractive league wear to Simply. Not. Care. What. You. Think. The ultimate superpower. Blue Bowling Ball Man will play his game, his way, for the win. And have fun doing it.

May we all join forces against the fierce “Pink Bad Guy,” whose portrait looks like just a hot mess of disorganized, naked human frailty, fighting against all of us as hard as possible. Maybe Bruce Banner can tame this brute, too, in time.

Or maybe we can each tame Pink Bad Guy, using our words, like Yellow Scrabble, and our brains and self-compassion, like Bruce, and our devil-may-care individuality, channeling our inner Blue Bowling Ball Man. Wishing us all the strength and endurance to let go when what we’d really like to do is just smash, smash, smash; to keep trying to turn that split into a spare, using a little English to turn things around. Heroic indeed.

June 21, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

a title is a brand

is a name

not your name

gotta take it to the

bank gotta

go gotta win gotta

cheering with the crowd

out

loud

gonna give it to the sun

gonna run

someone

gonna show you what I

mean

unseen

this scene

like a name is gonna fly

that lie

who’m I

_____________________

As I think about the book, I remember skimming bindweed with an iron rake, her tossing everything over the compost fence, descending the steps into her disease and my history, her knitting in that rocking chair, shoveling snow like memories, driving the jeep like I needed four-wheel-drive to cover the terrain of dementia, always caught off-guard flat-footed and unprepared, a pilgrim being burned at the stakes, Dad pitching horseshoes, the black wall of tornado, driving for yarn and lakes and singing with Mr. Rogers and finding stepping stones to make our way through.

_____________________

The Path of a Tornado

title options

Crazy Weather

I have considered

Bindweed & Iron

and pushed off onto a side table to look at later

____________________

Basho’s haiku written in 1686:

the old pond

a frog leaps in

sound of the water

The master of wabi sabi: the ephemeral beauty and deep meaning of simple, homey objects weathering, gaining patina before utterly crumbling away; “both the passing of time and time transfixed”

Weathering: the wabi sabi of Alzheimer’s

Basho’s book written of his travels around Japan from March 27 to August 21, 1689:

The Narrow Road to the Deep North

As it begins, he writes,

The months and days are the travelers of eternity. The years that come and go are also voyagers. Those who float away their lives on ships or who grow old leading horses are forever journeying, and their homes are wherever their travels take them. Many of the men of old died on the road, and I too for years past have been stirred by the sight of a solitary cloud drifting with the wind to ceaseless thoughts of roaming.

Last year I spent wandering along the seacoast. In autumn I returned to my cottage on the river and swept away the cobwebs. Gradually the year drew to its close. When spring came and there was mist in the air, I thought of crossing the Barrier of Shirakawa into Oku. I seemed to be possessed by the spirits of wanderlust, and they all but deprived me of my senses. The guardian spirits of the road beckoned, and I could not settle down to work.

That title is taken twice already now, once by Basho, once by Richard Flanagan. Flanagan even had prisoners of war. Everything I do is already done.

_________________________

Old Thunder

seems appropriate

old movie The Big Country

Dad’s favorite scene

nice haiku, but what’s the title of your book?

Dad’s Favorite Scene

now tell me, what did we prove?

any advice? don’t do it.

_________________________

Stretching my Patience

Walking fence

stretched wire thin

_________________________

It Was a Dark and Stormy Night

Edward Bulwer-Lytton wrote that, I found out years later. The author of, “Patience is not passive, it is active…it is concentrated strength.”

He also wrote, “There are two lives to each of us, the life of our actions, and the life of our minds and hearts. History reveals men’s deeds and their outward characters, but not themselves. There is a secret self that has its own life, unpenetrated and unguessed.”

__________________________

A Pilgrimage to My Motherland was written in 1860 by Robert Campbell, he who traveled back to “the Egbas and the Yorubas of Central Africa” from America. A black man leaving America, taking his family far from these troubled shores. Poor timing to be usurping the title of his book, I think. As if it was ever anything but a poor idea.

__________________________

Mom or Mommy in English.

In Japanese: mama.

So that’s just spooky, not helpful. Still chasing a title. Still searching for the hidden meaning.

May 17, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

“The first step to getting what you want is to have the courage to get rid of what you don’t.” — Zig Ziglar

I’m struggling with my character development. My book character. Which also happens to be me. So, again, I’m struggling with my character development.

I’m trying to figure out (for the reader, mind you) two small ideas:

1) What’s my motivation?

2) What do I WANT

In a nutshell, I need to give you someone and something to root for, to cheer onward to the goal. And since this book is about this character (let’s call her, oh, “Barbara”) who does not have a back story of people rooting for her, this is somewhat foreign territory. Let me think out loud here for a minute.

At first, I didn’t understand the character roles. I wrote the book about one fascinating character – who, it turns out, is actually the antagonist. This character, Barbara, is the actual protagonist of the story.

Surprise twist! I did not see that coming.

I did not see that I am the primary character in any story about my life. How interesting is that? Professionals, feel free to weigh in. Meanwhile, back to character development.

This character’s stated reasons for coming to Alzapalooza are so thin they’re more like 2-D geometry than 3-D real life:

- The character decides to help simply because she can? Who believes this line? I certainly don’t.

- The character is between trips and needs a place to crash? Reeeally? At her mom’s? I think not.

- Maybe the character wants to help her sister? Ehh…weak…because why?

I think we need to examine this “Barbara” character (if that is in fact her real name) and look at what she has given us to work with in the initial 3 stories of the first chapter.

- She is armored heavily against her mother, whom she hasn’t seen/talked to in seven years – hostile relationship!

- She is going on a 600-mile hike across Spain

- She’s “a person who keeps her word”

- Her mother gets diagnosed with Alzheimer’s

- She’s concerned about “the job” that “needs to be done” related to her mother

- She seems to live in New Mexico & drives a jeep

- She’s solo, a poet-artist person, divorced, with five kids – most grown, one finishing high school

- She has a sister who’s also a divorced parent, that she is worried about because she’s taking on too much with their mother – sister is thinking of moving in with mother

- Mother has asked our protagonist to stay with her – yikes!

- She has brothers who live in Florida who show up/leave quickly, she hasn’t seen them in years either, doesn’t trust one of them (oh dear, that feels like heavy foreshadowing)

- She’s a “watcher” in social settings

- She thinks she has the least to lose in terms of emotional risk with the mother

- She’s leaving in the fall for Japan

First take on examining that list: what this character has given us to work with = NOT MUCH.

It’s almost all external. She notices landscapes, and weather patterns, and elements of place. She feels quite distant, emotionally guarded. She feels like an outsider who won’t let us in. I don’t even know what her job is, how she’s just driving around, traveling to Spain, to Japan…?

Hmmmm. Still feel stuck. Finding a character’s motivation is like having the character go to therapy: “Tell me why you’re here.” Maybe that’s exactly where to go next:

“Welcome, Character Barbara; my name is Therapist Avatar. You came from…New Mexico, is it? To be your mother’s caregiver? Tell me how that all came together, how you decided to do that in three quick little stories.”

“Uhhh…I…don’t really know. I think there was probably a lot going on in my head that I didn’t really share.”

“Say more….”

“I knew you were going to say that. Um. I dunno, that’s so long ago; I’m trying really hard to care, because I just want to get this book done.”

“You’ve been working on your book a long time.”

“Oh for the love of god – STOP THAT. You are ME.”

“Sorry. Go ahead.”

“Jesus. Okay: what my character wants is to get things done that need to be done. That’s stated, that’s in there. Character has emotional issues: check. That seems clear, this person seems a little wounded, a little broken. But they’re also a seeker, a spiritual seeker, trying to learn, grow. Is that in there?”

“No. That doesn’t come up until page 26.”

“How about if I beef it up in the New Mexico travel bit?”

“You could try that. Is that your motivation?”

“Would you just – again, ME….”

“Right, yup. Continue.”

“So – a get-er-done mindset: that’s practical? work ethic? Duty? Flawed emotionally: we can relate to that. Spiritual seeker: common for broken people.”

“These are character traits, not motivation.”

“UGH. Let. Me. Work. On. This….”

“It’s -”

“NO.”

“Just -”

“NOT. NOW. I told Emma I’m going to trust myself, back when I wrote this, that as I was creating the journal, some part of me, my subconscious, the best writer in me, was crafting the storyline without me knowing it. I’m going to trust the storyline to tell me the answers.”

“That’swhatIwasgonnasay. Yousaidthatearliertoday.”

“FINE. Thank you.” Sigh. “It’s in the beginning then. So let me look at it: I’m leaving, and without her knowing that I’m on my way to Spain, she and her counselor call me to come meet. Weird spooky blood magic. That sets us up for any Camino magic I want to introduce later. That doesn’t – that doesn’t matter here. Anyway: she apologizes for her most recent ‘worst thing’ in her long-running series to be entitled ‘Worst Thing Lately’: she apologizes, sincerely, for being horrible when Dad died. So here’s Dad. And his death. And she admits ‘I wasn’t there for you.’ When do I tell you I promised Dad to be patient with her for a year?”

“CanIgoahead….”

“Yeah, yeah….”

“Thank- all right yeah – that’s, that’s page 62. Of the pre-edit version. Mid-April, of your book that starts beginning of March basically.”

“Hmmm. The promise to Dad seems huge.”

“So significant.”

“REALLY? With the counselor amplification thing?”

“I – just – so do you maybe want to punch that up? I mean….”

“Huh; doing it for the death-bed promise to the good dad seems pretty believable. And – actually, as I think about it, I do think that is the motivation. Well yeah, of course it is, I end the book about Dad. He’s the ‘Mentor’ figure in my Hero’s Journey, here.”

“You’re on a ‘hero’s journey’?”

“I’m ALWAYS on a hero’s journey. Where have you BEEN?”

“I mean -”

“I ALWAYS have ‘Hero’ motivation.”

“Mmm, do you….”

“I know, I act like an idiot, but my motivation, definitely always Hero. Hello? I’m Aragorn. I’m Han Solo. I’m freaking William Wallace.”

“So we’re going for flawed hero.”

“Of course flawed hero. The BEST heroes are flawed heroes.”

“So now you’re the BEST hero.”

“GAH. I cannot win here. Hear me out: my character is super flawed. With a decent-to-good father/mentor/role model, who taught me to do what’s right as I understand it, no matter the cost. Stand up. Take action. Do the right thing. And then he asked me to be patient with her. And in my mind and heart, I answered: I’ll give her a year. And at the end of the book, I realize the year I have given is the Alzheimer’s year, of actual patience, not the year of gritting my teeth and letting her be awful. That was actually avoidance. This was actually taking action, doing the job I was sent – by Dad – to do. I want to honor the promise I made to Dad. And then I can be free.”

“You’re on a mission.”

“I am ALWAYS on a mission.”

“You think it’s the promise you made to your dad, then?”

“What else would it be?”

“It’s that, yes. And…do you see what else you just said?”

“‘I can…be free’?”

“Better go add some of this to those first three stories.”

“You think that’ll work?”

“You mean, do I think that’s motivation a reader might understand and root for? Promises kept to those we love, and giving everyone, including yourself, freedom?”

“Yeah. Does that work?”

“Yeah. Yeah, Barbara, I think that’s enough, that’s enough. That’s more than enough.”

May 10, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Driving west from Albuquerque is infinitely better than the travel videos I’ve been watching online. Rolling across the easy hills like a tumbleweed, I pass through one entrancing vista after another, sipping ginger lemonade and humming along with the stereo from the best seat in the house. The afternoon light is more honest than video, highlighting the soft green of new growth dusting the desert in early May, growing hazy and indistinct as I look to the far off mesas, their stair-stepped horizon.

All along the highway, electric signs flash warnings that Gallup is still locked down, “no services available.” My daughter lives in Gallup with her family, at the epicenter of New Mexico’s current coronavirus outbreak. Temporarily under siege, she assured me over the phone that she planned for the long haul on her last shopping trips, stocking her pantry with non-perishables. But the kids are so small, just 5, 3, and the little one having her first birthday this weekend. They don’t have ice cream for her big day; they don’t understand why Mommy won’t give them more baby carrots and apples, rationing the fresh produce to make it last. I taste the extravagance of my lemonade as I finish it off. I have veggie chips and an apple in my daypack.

I take the Quemado exit but turn right, skirting the small, rundown town of Grants, turning right again at the storage units, following the signs toward Mount Taylor. I pass the privatized local jail facility, “CoreCivic” proclaimed on the gate; that’s the truth, I think. Between Grants and neighboring Milan, you can count three sites for incarceration, two of them on this road.

I note another sign just before I pass the larger prison complex. “Do not pick up hitchhikers in this area.” The shoulder of the road widens for inexplicable reasons, the next sign noting, “No stopping except for emergencies.” I think I would drive on a flat tire rather than stopping in front of this razorwire-bound fortress.

The prison is a landmark I watch for, ironically, telling me I’m almost to the gates of freedom. Around two curves of the road, I see the National Forest sign: “Continental Divide Trail.” Following the Rockies high and low, the Continental Divide marks the North American watershed, dividing waters flowing west to the Pacific and those flowing east to the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic. I turn right a third time, onto a short, deeply rutted dirt road into a dirt parking area that is always sparsely populated.

I’m learning to judge my trail access by the way vehicles are parked. If a couple of dependable, used SUVs are aligned faced into the boundary fence, a few hikers are on the trail. If an older pickup with a topper is backed into the farthest corner, hiding its license plate and activities, that could be anything from someone staying overnight to drug dealing to do-it-yourself shooting range, using your empties as targets. Today, a ratty compact sedan with no hubcaps is the only vehicle, parked dead center in the lot, angled for a quick escape. Sure enough, as I park at the boundary fence, three young guys immediately exit nearby brush, carrying on a forced conversation about absolutely nothing in voices tuned to be heard. Clearly up to no good, I watch them load into the car and peel out, tires throwing rocks, straining the buzzy engine of the sun-bleached little Mazda as they hightail it down the highway. I strap on my pack, click the beeping lock button on my car key, and stride through the gate and up the steep trail, moving fast, wanting to remain unseen just in case they decide to come back.

It’s 3:30 on a mellow Friday afternoon, perfect, sunny, a cool breeze keeping the temperature in the mid-70’s. Having put in extra hours at the beginning of the week, I’d let my boss know I’d be leaving early today, and he’d encouraged me to go.

It’s 3:30 on a mellow Friday afternoon, perfect, sunny, a cool breeze keeping the temperature in the mid-70’s. Having put in extra hours at the beginning of the week, I’d let my boss know I’d be leaving early today, and he’d encouraged me to go.

It’s weird having a steady job during this second Great Depression. Over 33 million Americans have filed for unemployment in the last seven weeks. I’ve been reading the New York Times: one in six Americans has lost their job in the pandemic, and the number will only grow.

lightning-struck tree

Millions of people have filed for public assistance benefits in the past two months, in some states double the total applications for all of 2019. Cars fill stadium parking lots across our country and stretch two and three miles as people wait hours for food boxes. “Mortgage loan servicers,” the new name for predatory lenders, prowl like wolves. The working poor continue to rack up debt as they wait, hoping to be recalled to their hourly jobs.

My hiking trail winds around the edge of an incredibly steep hillside. Shrubs I do not recognize, with tiny green slivers of leaves, pink buds, and small four-petal crosses of white flowers, cling just below the narrow path amidst the rocks and cactus, offering a hint of fragrance. They are cliff fendlerbush, awkwardly named for Augustus Fendler, “the first academically trained botanist to collect plants in and around Santa Fe, New Mexico,” in 1846, according to the Forest Service. The prettier name is Navajo orange, K’iishzhiní, listed on New Mexico State University’s website “Selected Plants of Navajo Rangelands.” I like the Navajo word best, the soft sound capturing the sweet enchantment of this unexpected garden along such a treacherously narrow margin. I find this bush’s tenacious optimism encouraging.

Less than an hour on the trail, I step beyond the scraggly junipers to reach the mesa summit. Here you can take in a panoramic view to the south, layers of hills slowly fading into the distance. Foothills of Mount Taylor block my view to the east, toward Gallup. However, mere steps to the west, on a tall post held steady in the center of a rock pile, someone has attached an old brass bell. It hangs at about face height, patiently waiting over the course of years for the dusty human beings who’ve made it this far to ring out the sound of their existence over the valley below.

Every bell is a bell of mindfulness, asking me to pay attention, like the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Han has tried to teach me through his books. I pick up a rock and tap the bell, and a soft, sweet note rings gently, a fragile voice that whispers away on the wind: K’iishzhiní.

After a drink of water, the trail leads me north across the open tableland, evergreen scrub circling the edges of the mesa. Here, grass grows in dry tufts scattered among a vast cobble of volcanic rocks. The trail gently sways to the left and right, like a cow path through pasture. Nearby lies evidence that this may indeed be the origins of this stretch of trail: dessicated cow dung bleached nearly white, their cloven hoofprints hardened in the dry orange clay by the ever-present wind and sun.

After a drink of water, the trail leads me north across the open tableland, evergreen scrub circling the edges of the mesa. Here, grass grows in dry tufts scattered among a vast cobble of volcanic rocks. The trail gently sways to the left and right, like a cow path through pasture. Nearby lies evidence that this may indeed be the origins of this stretch of trail: dessicated cow dung bleached nearly white, their cloven hoofprints hardened in the dry orange clay by the ever-present wind and sun.

Out of habit, I scan the treeline, watchful for wildlife, friend or foe. I’ve picked up a walking stick along the way, weathered grey, worm-trailed, but solid at its core. On my last hike up here, I’d found what looked like bobcat or coyote scat, full of rodent fur and tiny bones. But today, my only companions are birds, ravens overhead, warblers and sparrows singing from their distant branches. I pass through the first line of trees and across the next lower mesa. I wend my way through more juniper and split cedar.

Now coming over a rise, I see a pristine valley opening to my right. No roads, no fencelines, the kind of high meadow within tree-covered hills favored by elk. This is as far as I’ve been on the trail to-date, and I happily continue around the next hillside.

The landscape becomes more of a low forest, and the farther I hike, the taller the trees grow, short-needled fir, spruce, and white pine, until I’m suddenly surprised to find myself on the top of yet another rounded mesa in a spreading grove of nothing but fat piñon. Just as I think it, I see it: elk droppings beside the path. I venture on, tall trees rising once again, white pines stretching higher, wondering if those are ponderosa I see, the harbingers of mountain trails.

As I reach a small gap in the forest, I notice two things nearly simultaneously: a view of Mount Taylor, looking closer and more attainable than ever, and another Continental Divide Trail marker nailed to a tree. This one’s a tiny little pine, with two angled branches of thickness similar to the central leader, all splitting from the same location. The effect is of a hand holding up three fingers, like a reminder of something, something I’ve lost count of. I look at Mount Taylor, pondering the little tree while perched on a low limb of a particularly spectacular piñon, the ground under my daypack littered with its wasted abundance. I nibble my veggie chips and chomp into my apple.

It’s 6:00. I have to turn around if I want to get down before dark. But how I wish I could just keep going, for days. I imagine hoisting my larger backpack, tent and sleeping bag secured, and wandering away, away from the day job I am lucky to have, away from cars and video screens and politics and reactionary people fearful of the unknown that lies ahead of us all.

At least I have walked beyond my worries today. Zipping my daypack, I feel wistful as I turn back,  and something else, something stirring within.

and something else, something stirring within.

Tapping along with the walking stick for an hour or so, I meet a young woman on the open mesa. From a distance I note the big pack, rain jacket, and quick-dry shorts. As she approaches, I see a carton of what I presume are hard-boiled eggs lashed to the top of her backpack. I step aside, giving her safe distance to pass.

“Have you seen anybody else on the trail?” she asks me by way of a greeting. A familiar style of greeting. And as she says it, I feel joy, as if I have come home.

“No, nobody,” I smile at this stranger. “How far you going?”

“Just to Cuba.”

“How far is that?”

“Mmm, maybe 90 miles.” She cocks her head back and forth between empty hands like scales, the gesture of the we’ll-see-guesstimate: “I’ve got food for five days.”

“You’ve done the Continental Divide Trail before, the whole way?”

“Oh yeah. I’ve done all of them.” She grins, the pink streak in her blond hair shining in the afternoon sun. “I’m one of those people.”

I smile broadly. You’re one of my people. Before we part, she tells me that since she’s now unemployed, she’s heading back onto the trails, reconnecting to that part of herself she loves  most and has neglected in the city.

most and has neglected in the city.

And there it is.

It’s been three years since I went trekking across Spain. Signs and messages come in threes. As do prisons.

So many things cancelled, locked down. It’s hard to feel free. Yet my first book still goes to the editor in July. Ring the bell: I’ve made it this far.

Maybe I could follow that familiar stranger, joy, hike over Mount Taylor, all the way to Cuba, or beyond. Use some paid time while I have it. While I’m well. While I wait to hear what comes next.

As I reach the overlook, I turn right, to face the setting sun. Standing in the warm rosy glow, chewing on a twig of sweet-tasting Navajo orange, I contemplate the unexpected abundance of my life, spent constantly walking the Great Divide.

As I reach the overlook, I turn right, to face the setting sun. Standing in the warm rosy glow, chewing on a twig of sweet-tasting Navajo orange, I contemplate the unexpected abundance of my life, spent constantly walking the Great Divide.

Water only flows to one sea or the other. But first, it comes to us as rain. In this way, somehow even the desert blooms.

K’iishzhiní, whispers the evening breeze.