July 23, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Here’s how I have to approach you: I have to circle back around. Like livestock that got out through a broken fence, I have to calmly gather you back in to what I’m saying. Getting mad won’t help. I tell you my latest idea, and you immediately bring up the other side of the argument. As if I’m both a curmudgeon and an idiot, now that I’m fifty-four. As if I’ve never gathered hogs. As if I need you to show me that other people have other intentions. Other approaches.

You quickly tell me about an amazing essay you read, by someone closer to your own age. I listen carefully — then get to just as carefully use your story as an example of exactly what I just told you. Now, with your peer’s frame of reference, now you can begin to hear me. Now I’m not old and bitter and judgmental. Now it becomes possible that I’m just noticing. Like the amazing essay author.

My point became lost as I tried to put it into words. Farm references don’t always translate well to urban issues. More than that, words struggle to bridge generations. They always have. How many times, I wonder now, did my dad, my grandpa and grandma, my uncle with his wry, witty reflections — how many times did they try to tell me some very simple observation about life, and I hurled their small pearl of wisdom into the hog lot like a rotten apple?

Intelligence is not wisdom. I’m on a bridge between these two shores, without a foot touching either side at the moment. It’s raining, here in midlife, a sudden downpour that tried to warn me by sprinkling little showers here and there as I attended to the tasks at hand, thunder rumbling like a scolding. This bridge stretches between the heavy smell of wet hogs fenced in their pens and the warmth of Grandma and Grandpa’s farmhouse. I’m walking the sloppy gravel drive to get there, hair plastered to my head, my chore boots a mess of wet manure and mud, but the sheltered metal porch chairs sit welcoming and familiar, a safe place to pull those boots off, peel off dirty, soggy socks, and wipe my dripping face with my wet sleeve, fingers finally slicking my hair back from my eyes. How many times did I wait on that porch in the rain, noticing, as if I alone could witness such a storm.

I remember the quicksilver brilliance of my youth, concepts and decisions flashing like a mathematician’s chalk on a blackboard, like a musician’s improvisation, like a poet’s voice, the microphone close and seductive, my lips spinning everyone into the dark room with me.

I miss a step now and then, here on the bridge. I feel it, sometimes clumsily, like I’ve stubbed a toe, or sometimes like I’ve caught myself just in time from landing on a rolled ankle gone soft right when I needed its strength. And sometimes, I still feel the foot that for whatever reason didn’t come as far forward as I meant it to, dragged itself ever so slightly, still lingering just behind my intention.

I wonder about Parkinson’s. I think of my grandma’s congestive heart failure. I make my uncle’s doubtful expression at the memory of anesthesia, surgery to save my life burning the bridge behind me, no way back to brilliant now. I have my mother’s tremor in my right hand. I have my dad’s creaky ankle that burns and aches if I drive too long, his lower back that is corkscrewed into wide, flat hips. I think I’m my own person, when even my smile is a blend of the two, her smile on top, his below. Every bit of my uniqueness is built of hand-me-down gifts.

You’re so young, so brilliant, so sure. Yet I wish again, for the hundredth, for the thousandth, for the millionth time, that I could bring you inside my heart and mind, help you see what I see. Convince you that I notice, and I care, deeply. That my words that so irritate you are the gritty, sandy seeds of your own growth. That everything you think you need to teach me to see, I taught you to see.

I wish I could tell you about life without you subtly correcting me. The ones fit for that task have long since crossed the bridge and traveled away. I am more familiar with this bridge than you are, have stumbled along more of it, have been walking in the rain so much longer than you have yet even been alive. Before I get too far along the way, let me circle back, and place these few small pearls in the palm of your hand. There aren’t many, but they’re all I have to give you.

Do with them what you will.

July 14, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

First, I thought they were hummingbirds. Barrel-shaped bodies flitted among yellow-dusted blossoms hanging under lacy leaves. From my desk at the window, I watched them swoop on buzzing wings through the slender locust tree growing between the sidewalk and street. I imagined hanging a red nectar-filled feeder by my back door. But it’s all adobe, my back wall; there’s nothing to hang a feeder on. And they weren’t hummingbirds.

Then I thought they were cicadas. I saw one that was a coppery-brown, another darker, and since I have only known cicadas by their heat-gnawing summer song and husks of abandoned skins left clawed into tree trunks and branches, I guessed they might fly in looping arcs if given the chance.

However, it appears they are a type of huge bee, built like a bumble bee but without the bad temper of that chubby garden tyrant. Carpenter bees, who chew a perfectly circular hole into any unpainted, untreated wood to make a nest. I read that the males can be aggressive when protecting the nests; yet even if they dive-bomb, they’ve got no stinger, so what do they do? Head butt? Body slam? The females have the stingers, but it seems they rarely use them. Females prefer to stay in their wood tunnel burrows. You have to provoke a female carpenter bee to get stung.

I keep encountering how much I don’t know. Like the last time I went running at the volcanoes. I saw a very looonnngg baby rattler stretched halfway into the trail, which, upon second look, I thought probably wasn’t actually a baby rattler. This snake’s head was shaped differently, and the body seemed to shine with a coppery stripe, though toward sunset, who can know what they’re really seeing. The thing is, this snake looked fast. I can’t explain this to you, except that upon seeing this very looonnngg baby rattler, entirely unmoving, unblinking, I just knew. This makes no sense, I realize, and I’m with you in being annoyed that I would state as fact what I clearly don’t know.

But life is like that.

Striped whipsnake. Belonging to the snake family of “racers,” colubridae, they’re incredibly fast: fast as a whip. They typically grow to four feet long, hence their nickname “coachwhip” (think stagecoach). Whipsnakes are often found draped in bushes like tiny anacondas, or heads-up on the ground, their faces little periscopes above the cactus as they glide across the desert sand, searching for something to eat.

Whipsnakes are generally nonvenomous. Also not constrictors. They are typically harmless to humans, though a bite still wouldn’t feel good. Nevertheless, their prey includes lizards, frogs and toads, ground-nesting birds and small mammals, even other snakes – including rattlesnakes. So how do they attack? They just rush their prey and eat it ALIVE. They. Eat. Rattlesnakes. Alive.

Appearances can be deceiving.

I remembered the carpenter bee and the whipsnake as I drove out of Albuquerque this weekend to escape daily temperatures of 105 degrees. I am not native fauna. A Colorado transplant, I realized the enormity of my error last summer; now, as July has unfortunately arrived again, I have forsaken my cool, dark cave of lethargic exhaustion in an attempt to escape. I am a mountain ground squirrel running frantically up the highway, hoping to find my habitat before my feet melt into the black pavement or I am crushed by the stampede of traffic behind me.

Against my usual prerogatives, I’m heading to Santa Fe. My hiking guidebook tells me I will find Nambé Lake at 12,000 feet. My flushed face and sweating body tell me I will find cool air and cold water within the high cirque holding this precious source of the Rio Nambé.

My bias against Santa Fe stems from its faux-adobe-suburban vibe, a city of seemingly over-educated, overly-thin white people who epitomize one stereotype of Santa Fe, salt-and-pepper haired arts patrons dressed in quick-dry shorts and web-strapped sandals, sunhats and sleeveless T-shirts baring old, brown arms, silver rings on several fingers.

People who look uncomfortably similar to me. I notice my hiking wear with dismay, driving in my Tevas with their red-patterned straps. My rings flash atop the steering wheel.

I haven’t explored much up around Santa Fe. I’ve been to Chimayo and Española, Taos and the Rio Grande River Gorge. I stayed at Upaya Zen Center for a weekend. I’ve driven up and over the High Road multiple times. But of Santa Fe itself, I only know the plaza. I only know the roads that leave Santa Fe. I haven’t actually tried to enter and explore the mountains that hold this city.

As its name suggests, Paseo de Peralta lifts you up into the hills. This road winds until it reaches another, and another, until you find yourself on Hyde Park Road. I associate Hyde Park with rich people back East, and as I drive past custom fauxdobe homes, my heart simultaneously sinks and rises with the road.

These hillside homes are, in fact, beautiful. The walls act as mere frames for windows that showcase the surrounding views, vistas that stretch and relax for miles and miles of high chaparral and wide sky. Hyde Park Road, and Gonzales Road that led up to it, cling to the edges and pinnacles of ridges, one of my favorite features of New Mexico roadways. The air is already ten degrees cooler. I drive past several neighborhoods of condos and realize I’m scouting locations for my life, smiling at the northern New Mexico Territorial architectural style with which I have always been taken, stucco and protruding vigas and shady porticos and little walled plazas for yards, sprouting sage and wildflowers. I like it up here.

You drive to the end of Hyde Park Road to get to the trailhead. I pass Hyde Memorial State Park, 350 acres donated by a member of the Hyde family in 1938, New Mexico’s first state park. “Hyde Park Road” takes on a different tone, after that.

The road wraps the mountains, curving its way up and up, through tight canyons and into taller forests. Guardrails along sheer drops feel familiar. Mount Baldy to my left reminds me that New Mexico does have peaks that rise above treeline. The sight of its smooth pate refreshes my eyes and gives me hope for this hike.

I arrive at the end of the road, a large parking lot for the Santa Fe Ski Area, and find a small gap along the side to park. I can see the trailhead sign from my car – as well as dozens and dozens of cars and hikers and lounging RVers and young Instagrammers in stretchy “athleisure.” The place is swollen with hot, sweaty humanity. But I don’t care.

Because I have reached 10,000 feet above sea level. And even though the trail begins with a precipitous rise that finds me huffing and puffing, I am totally at ease being this out of shape, this high in the world. Ten thousand feet never felt so good. My legs strain against gravity and against a summer so hot it has left me sedentary and depressed until now.

As soon as I reach the initial point of exhaustion, stopping at a switchback, feeling my blood and breath pulsing hard, my familiar comrades join me: the butterflies.

A speckled pair of bright orange, summertime energy swirl around each other and soon around me, one alighting briefly on the top of my walking stick, the other on the knot of the extra shirt tied around my waist. I feel energized with delight and relief to meet up with them, my trail guides of longstanding mutual agreement.

As quickly as they greet me, they lift and spiral away over the wildflowers. And just as easily, my temporary exhaustion is alleviated by joy. As I squeeze through the V-stile log gate into the Pecos Wilderness, I feel that my butterfly friends have welcomed me home. I follow their lead, wandering off on side loops, retracing my way back, crisscrossing the drainage, stopping to admire the paintbrush and columbine.

Even as I take yet another water break, for the entire six hours I am on the trail, I never once think this hike is a mistake.

Listening to the running stream and birdsong, I do think I might have been wrong about Santa Fe, though.

July 9, 2020 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

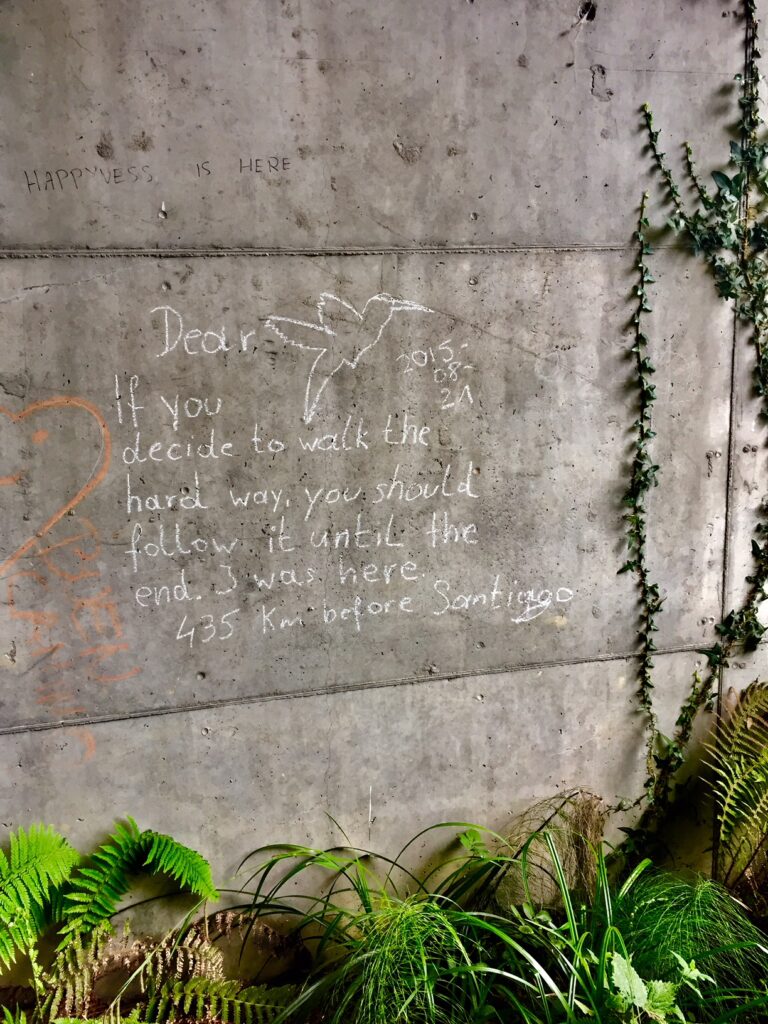

Turquoise. How could I know? The ocean rolls waves over the surface above me, a landlocked desert pilgrim on Camino, the path leading to sand and sea. Weightless, swaying with the water, I relinquish my brokenness to wonder. Fragments of shell, tumbled by waves against hidden stones, emerge with me upon the beach.

I have dreamed of the turquoise water again. I believe it is the water that calls to me while I turn and float in sleep. But the water is only the voice.

The unexpected color of the light, curling waves reflecting my own eyes to me – this is the soul messenger, the fantastic angel holding my wings for me, again, summoning me to put them on, again, and rejoin the larger world. Come, swim out into the ocean, says Wonder. Wings become fins, fins become feet, feet take to trails, trails take to stars.

I am dried out, parched under this sun of relentless

knowing. What I know is small, scuttles under rocks for shade, waiting for the desert air to cool. With nightfall, the Mystery closes my eyes and draws me forward, winding and finding my way by flicking my tongue, testing my thoughts for the faintest scent of life. Hungry, hunting for new experiences that can feed me. By day, I curl into my den, dulled by heat, waiting.

I don’t want to know. I want to find.

Wonder as I wander, under the sky.