tilting at windmills

everything

is the ocean

ebb and flow

cupping water in my hands

and splashing it on my face

like I did

to taste the sea

gulls of memory

always rising

The morning dawned gently, the sun rising on softest feet across a sky warmed by woven, woolly clouds. I walked the dirt path as quietly as I could, like a mother tiptoeing to the kitchen past the doors of her children’s rooms where they lay peaceful among their last dreams before waking.

Sheep grazed beyond the heather alongside the Camino, snug between a cornfield on one side, an old stone church walling the other, its bell hanging still and silent. A mist rose from the valley, washing over me as I strode along the high hilltops, then receding like a wave back from the shore.

When the fog finally lifted, there stood the windmills at last. I had attempted to photograph them each time I encountered them along the entire way, but until now, every opportunity had been thwarted by mist and fog. At one point, I walked a trail directly beneath the moving monoliths, but hidden in cloud, I could only hear a low, rhythmic rushing, the regular thump of their blades pulsing through the wet air, like the heartbeat of someone holding you close to their chest.

I wanted a picture of the windmills for Magnus. Before I left, we had watched a movie about the Camino. He thought the windmills were cool, impressive, and he would want to see them if he came to Spain. Now at last, I had them before me.

The thing I couldn’t capture was the perspective. I could see they were massive, but what my eye saw and what my photos showed were two different things. My pictures could not portray the enormity of the hills leading to the coast, or the power of the windmills, or the rolling of the thick clouds throughout the day. Photographs could not begin to match my experience of the Camino. More souvenirs. I would have to tell him stories, to explain.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Not far past the windmills, I came upon another small church, surrounded by an elaborately walled graveyard, all of this stepped down into the earth itself, terraced into the side of the hill. Nearest the Camino, a tall, stone pillar topped with a crucifix, a cruceiro, stood in a grassy yard,

a small, lichen-covered stone bench beneath it facing the church, and the mountains, and the graves. Best seat in the house, with a view of eternity. I read the sign: San Cristovo de Corzón. Christoph of the Heart. Unbuckling my hipbelt, I took off my pack, and set it on the ground.

Sitting on the small bench, I thought about the windmills hidden in the clouds. I thought about the sound of heartbeats, heard even from far away, or with your ear to the chest of one you love.

Sitting on the small bench, I thought about the windmills hidden in the clouds. I thought about the sound of heartbeats, heard even from far away, or with your ear to the chest of one you love.

I thought about the Plaza do Obradoiro.

I tipped my water bottle, tasting the faint residue of iodine from weeks before. Having been in Spain for over a month now, I no longer fastidiously treated my water at every refill. I had adjusted, like acclimating to altitude; I could drink the tap water like a local now. I could trust the world to sustain me.

I drank another long swallow, and sat looking at the wall protecting the cemetery. Stone angels stood at the peak, facing each other. Beyond them, crosses lined the top of the wall, stretching away toward the mountains, toward the sea. The pattern repeated over and over, like the far-off windmills spinning their blades in the strong winds that kept rolling the clouds beyond me.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I ended my day walking with a young man named Jerome, from Germany. He was a social worker employed at a children’s home that was more like a fairy tale camp. He described the small timberframe houses on a hillside as “like the setting of the story of ‘Heidi’ – you know this story?”

Jerome usually walked very fast, and very far, but he fell in step with me as we talked, and so we arrived together in Dumbría. He asked if we could walk together again the next day, to arrive in Muxia together, and I agreed, because the conversation was interesting and meaningful.

The children sent to live at Jerome’s site were temporarily removed from their homes as part of a larger plan to eventually reunite the family, if at all possible. Jerome insisted that his job, as well as that of most of the staff, was simply to be an adult role model, offering safe relationships and consistent caring regardless of the child’s choices or behaviors. The child’s point of view was not only accepted, but respected. The child was valued, taught that they had value, because they usually arrived abused or neglected, feeling broken and invisible, worthless. This typically changed over the course of the 1-2 years of their stay in the picturesque Heidi village. A healthy self was found and cultivated. A “You” was nourished. They emerged, blossomed.

In Dumbría, I walked to the tiny market in the back of the bar down the road. I found a few items, an apple, bread, cheese. I took them to eat beside the local stone church, Santa Eulalia Dumbría. Saint Eulalia was only 12 or 13 years old at the end of the third century when she was tortured to death for believing in a God that loved her.

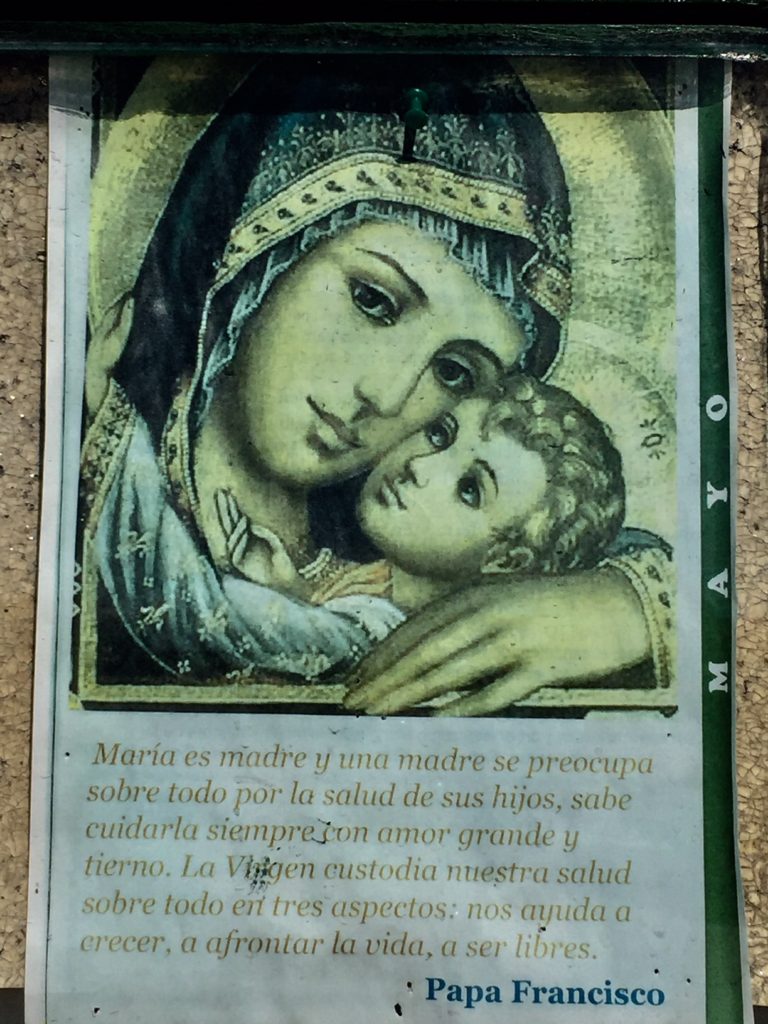

I compared this story to a poster hung beside the door to the church, reportedly a quote from Pope Francis:

“Mary is a mother, and a mother cares above all for the health of her children, knows how to take care always with great and tender love. The Virgin keeps our health above all in three aspects: helps us to grow, to face life, to be free.”

As I looked at the face of La Virgen, I silently hoped Magnus was receiving these intended gifts of great love. It was part of why I had come on Camino now. And why I still carried lingering doubts, my walking stick Saint Thomas still marking the Camino with every step.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Next morning, I set off with Jerome in a light drizzle that soon ended. Our stops were brief, and we made good time, having found a compromise pace between our two extremes. Our conversation returned to social work, and parenting, and soon we talked of Magnus.

I loved Magnus’ father. When it quickly became clear that he had been wildly idealistic about step-parenting four other children, including teenagers, and was overwhelmed and out of his bachelor depth, we separated – but now we had a baby.

He was wonderful with the baby. He adored Magnus. He watched the baby during the week, and I took him on the weekends. I promised him I would never take Magnus away from him. But I couldn’t promise that Magnus wouldn’t step away himself – which he did, at the beginning of high school. He asked to come live with me, for two years, while he and his dad worked on their relationship on the weekends.

Nothing about Magnus had been my idea, except his name. His father had so wanted a baby; I was resistant, having four already. But love often steers us to sail the seas against our better judgment, under thick, rolling clouds, in a ship of stone that can only reach the farther shore by a miracle. In love, I agreed, but added, “You have to be the one to take care of this baby – because I have things to do.” I had already put my creative work on hold for years; I knew starting over, a new child, would delay this work for years again. And I couldn’t bear it any more, the waiting.

I had already begun to write songs again. Finally. I had met Magnus’ father when I went searching for a guitarist – I found both in the same month. So as my belly grew, I sang. Holding an infant in my arms, I sang. Dropping him off at his father’s apartment, I went back to work, and once every week, after work, I drove out to the studio, and I sang. And when at last I recorded a CD, and my guitarist handed the master to me, I went straight to that apartment so Magnus’ father could hear it.

I knocked at the door at 9:00pm. Magnus was already in bed for the night. His father opened the door, and I jingled the CD case like a magic wand in my hand. “It’s done!” I said, excited. “Want to hear it?”

An odd pause filled the open doorway. “I’m…pretty tired,” he replied.

“But – it’s done – don’t you want – ” I faltered. “Ah, okay,” I managed. I turned and walked back down the stairs. I don’t know what else was said. Maybe we agreed to listen to it later; maybe he just said goodnight. I didn’t even care why he hadn’t let me in – maybe he was actually tired, maybe he had a woman over, who knew. The reason didn’t matter. He had shown no enthusiasm, no interest whatsoever. It was as if my guitarist was “the other man,” as if my songs had broken us up somehow, not our ill-conceived relationship itself.

The CD had taken five long years to complete. His response broke my heart. Magnus was starting school soon. I was done.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In The Artist’s Way, author Julia Cameron describes a creature called “the shadow artist.” This person is a creative spirit as well, but quashes that spirit in themselves and those around them, even as they are drawn to other artists like a moth to that holy flame. Theirs is a resentment based in fear and longing. It is the love-hate of a deep wish to rise into that light, tied like a heavy anchor to an expectation of failure which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

My mother had been such a creature. Now I had another in my midst. Magnus’ father was an artist who sold off all of his tools, gave up on creating, and now bought and sold everything and nothing online. He barely got by, a starving artist who no longer made art. I had chosen a tie that bound me to my day job, my desk job, the steady paycheck security of hearth and home.

But when I looked at Magnus, I was torn. Here was the creative spark of two artists, joined in one soul. One beautiful, musical soul. I vowed I would not remain in the shadows. I would teach him about the light.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

“Are you sure you’re not making a mistake, sending your son back to his father?” Jerome asked as we marched steadily along the road.

“No, I’m not sure. But it’s what he wanted, to go back to his dad’s, his hometown. They’ve been working hard on their relationship, I know that. So we’ll see, at the end of this summer, how it’s going.” I had offered this “out” to Magnus before I left, deciding I’d figure out a Plan B if it was needed.

“But is it the child’s responsibility, to determine what is best for him, what he needs?” Jerome continued. “Are you choosing based on the needs of the child, or for the father, what the father wants, and your love for him?”

I thought about my promise never to take Magnus away. But I never promised Magnus couldn’t choose for himself. “Sometimes I do forget how young Max is. He’s just starting his junior year, this week, actually.”

He had the sense of humor of his older siblings…he kept up with them in conversation. Ready or not, he was about to make life choices, apply to college, enter the world. It was easy to forget how young he was, because he tried so hard to be mature. He also fought for respect with a fiery temper and a fierce pride; I was not confident I could dissuade him from any choice he decided to make, once his mind was made up.

“I hope I am focusing on him in this decision. I believe I am.”

I had known my travel would be hardest on Magnus. For the first time, I was stepping away from him for months, not days. But I also knew, just as clearly, that I had to do this. I knew the timing appeared terrible for his life; I knew it looked disruptive. But I was at an imperative in my own life: the dissonance of who I had always felt myself to be, and who I was being, was so uncomfortable, so painful, I had to resolve it.

Whether Magnus fully understood it or not, I was rising up. I saw clearly that he was fast approaching the age when I had disregarded my own dreams. I would raise my self-doubt like a lance, to show him how windmills and their patterns of shadow were defeated. What appeared to be giants were simply not so.

I glanced at Jerome. I trusted the dreams of adolescence, with everything inside me. I believed Magnus was the only person to decide what was best for him. My job was to encourage him to dream, well and true to himself, and help him to grow into that self, to face life, to be free.

I would show him how.

“Now look, your grace,” said Sancho, “what you see over there aren’t giants, but windmills, and what seems to be arms are just their sails, that go around in the wind and turn the millstone.”

“Obviously,” replied Don Quixote, “you don’t know much about adventures.”

— Miguel de Cervantes

the best words anyone gave me before you

were you’re gonna be all right

you’re gonna be all right

the best words anyone gave me before you

were you’re gonna be all right

you’re gonna be all right ….. all right ….. all right ….. all rightthe best gift anyone gave me before you

was how to sing the stars

shining where we are

the best gift anyone gave me before you

was how to sing the stars

shining where we are ….. and we are ….. all right ….. all rightthe best touch anyone gave me before you

never lasted long

before it all went wrong —but on that plaza of gold

where the cathedral bell tolled

like a bell our laughter’s sound

you swung me round

you swung me round

you swung me roundthe best words anyone gave me before you

were you’re gonna be all right

you’re gonna be all right

the best gift anyone gave me before you

was how to sing the stars

shining where we are ….. and we are ….. all right ….. all right ….. all rightwe are ….. all right ….. all right ….. all right ….. all right

— “All Right”