February 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

there is a bench

for two

beneath the cruceiro

at Cristovo de Corzón

Raining again. I unzipped the tent and looked out from under the tiny portico at the deep green all around me. Sheep like specks on the distant hills continued to graze, unperturbed in their fleece coats.

The bells began ringing. Two high, one low, then more, a tumble of bells, voices rolling, combining, rising, echoing. Smiling under my hood, I zipped the tent shut and dashed out into the weather.

Once inside the historic chapel, I quietly unzipped my jacket, shaking the water off in the vestibule quickly, as others were entering, too. We filed softly into the sanctuary.

I took off my worn hiking boots and sat down cross-legged on the floor, my rain jacket folded beside my boots. Before me, on the wide, stage-like altar, candles burned, dozens of red candles, held in a mesh of round-cornered black metal frames, like an imperfect honeycomb. I found a candle for me, and one for Christoph, as I did each day, the same two candles, not quite at the very top, somewhat to the left, in slightly off-kilter black shapes that leaned in toward each other, balanced well, but each in its own space. I bowed forward briefly, in thanks, as I did each day.

More people came to sit all around me, college students, newlyweds, parents of toddlers and teens, white-haired retirees holding hands. We squeezed in tight together, always making room for each other, sharing the space.

As the simple accompaniment began to play, the monks entered the sanctuary. Dressed in white robes, they came from all parts of the world, from all faiths, now one family of believers in a God who loved them. The monks entered into the sacred space in the center, between two wide masses of ordinary people, as we joined them: singing. Such beautiful voices, accents of homelands adding a new texture to old words, old tunes. I closed my eyes and listened, hearing Christoph’s deep voice among them; he had once been here, singing in this holy place.

The Omega and the Alpha. These had been carved, seemingly backwards, over the Pilgrim’s Door to the Cathedral in Santiago de Compostela. During that night of our tour, Christoph had leaned in close to explain to me that they didn’t know for sure why these signs had been placed this way. We decided we liked the obvious interpretation: “The end, and the beginning.”

The monks were singing in Spanish, my favorite. But by the next song, it would change, to German, or Polish, or English, or French. Often Latin. Here in Taizé, in France, the monks sang in every voice, as one voice. Four parts, blending melodies and harmonies, words and spirit, all seekers of the Sacred. I sat, among everyone I did not know, but loved, and sang my part, my voice rising in a counter-melody I was still learning. The song was a round, layers of meaning and voices woven over and through each other, spinning around, and around, and around, until you just lost yourself in the joy.

D.S. al Coda. In the language of music, this term means, “Return to the sign, and from there, continue to the new ending.”

I take the train

I take the train

nothing to lose

and all to gain

I take the train

I take the train

I walk along

beside the road

got what I need

no heavy load

I walk the road

I walk the road

by the train or my two feet

going where I go

jump aboard Life takes you there

knowing what I know

I take the train

I take the train

nothing to lose

and all to gain

I take the train

I take the train

I walk along

beside the road

got what I need

no heavy load

I walk the road

I walk the road

— “I Take The Train”

February 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

In the middle of a fine, warm day, Gorma walked with bare feet along one of the small, secret beaches of the Land of the Heart. She had come from one shore of this land to the other, walking the Camino day by day. The wet sand was cool and smooth, and Gorma’s footprints filled slowly with water before being washed away by the morning’s slow, gentle waves smoothly and softly covering Gorma’s toes. She was hunting for new shells for Saint Thomas, her walking stick, who always wore a charming necklace of white, yellow, or striped shells on a turquoise cord wrapped around him, turquoise like the color of a gentle sea.

As Gorma rounded a small cove, she found a big surprise! A sailing ship was anchored in the tiny cove, and a rowboat was bringing a woman ashore. The woman stood tall and strong as the boat neared the beach, directing the rowers past the rocks to the best landing site. As she hopped from the boat onto the sand, she gave Gorma a nodding bow.

“Gorma, Gorma! Too long have I sailed without a landing! And too long since we shared a meal ’round a beach fire, eh? Tell me, what treasure have you found today?” She gave Gorma a great, strong hug, and an even stronger smile of friendship.

Her name was Captain Cordula, and she and Gorma had known each other a long, long time. Her white hair fluttered like the sails of her ship, and the fleeting clouds passing easily overhead.

Gorma opened her hand to show Captain Cordula the shells she had collected. “I have also found one song, light as a bird upon the breeze,” Gorma added, smiling warmly in return.

“Then you may have no need of this, eh?” Captain Cordula said grandly, and from her jacket pocket, she pulled out a rolled cloth, and unrolling it with a flourish, she showed Gorma – a treasure map.

“Where have you gotten this?” Gorma asked, for one person’s treasure is another person’s trouble, and she was concerned about the source of such a map.

“I have drawn it myself, Gorma,” Captain Cordula stated proudly. “I have talked to the villagers and islanders along these coasts, to the fishing folk, and the barmaids and alemen, the nearby farmers bringing cheese and meat to the market, and many passing travelers. Never was such a true and trustworthy treasure map made!”

“Indeed, I believe you, for you are true and trustworthy as your fine ship upon the seas, Captain Cordula,” Gorma agreed. “But I could not help but notice – there is no X to mark the spot of the buried treasure on your map.”

“That is because it is not yet buried!” Captain Cordula laughed, and now Gorma saw her sailors carrying a quite heavy treasure chest from the boat. They set to work, pacing off the distance from the tides at this time of day, in this season, and from those trees growing beyond the sandy beach, and from that rocky point at the bend of the cove. Then, when all was measured and noted and recorded on her map, Captain Cordula set the sailors to digging, and to building a fire for a fine evening meal, for the afternoon soon passed with all this treasure adventure, as afternoons do on warm beaches under sunny skies.

As she feasted with Cordula on clams and mussels and sea kelp seasoned with the salt of the sea itself, the treasure chest was lowered into its hole.

“May I see the treasure, before it is buried?” Gorma asked, and Captain Cordula nodded, holding up her hand to stop the sailors and motioning for one to lift the lid for Gorma. Instantly, her eyes lit up, and her heart was glad.

“Why, this is everything needed to keep the land and sea beautiful and strong, always. This will keep the sea air salty, and the mountain lakes crystalline with ice,” Gorma said in wonder.

“Aye, and the jungles green and lush, the deserts quiet at night, and the monsoon clouds bringing rain over the highest peaks,” added Captain Cordula.

“This is the greatest treasure I have ever seen,” Gorma replied softly. “You must mark it well.”

“Oh, we will, Gorma, we will. Together.” And so, asking for a feather and a shell from Saint Thomas, Captain Cordula marked the treasure’s hiding place, buried well in the Land of the Heart. It is there for any and all to find, just waiting for an adventurer in search of the greatest treasure ever seen.

Gorma said goodnight and walked on down the coast, quiet and smiling. She arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. In the corner, by a window overlooking the sea at night, Saint Thomas stood quietly, as if he might want to go find a treasure chest under the sand, marked by a perfect shell, and a fluttering feather.

Buen Camino, Captain Cordula.

February 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Blessed Santa Barbara

your story is written in the sky

with paper and holy water

— Federico Garcia Lorca

Whom should I find when I reached Finisterre, but Jerome. After a long, hot day of hiking, I was please when he led me to the small, hidden beach he loved, and it was perfect – hardly any people, plenty of beach to nap on, and plenty of icy cold Atlantic water to play in. He said he could manage two minutes in it; I lasted for ten. Not only was the water colder, the waves came stronger, fiercer. It was exciting, less like a dance and more like competitive sport: I jumped, then dove under, ducked, then dove over the tops of waves, met by a face full of salt water, or the sound of a big wave going over, or an unexpected free ride backwards toward the beach.

Refreshed, I left to go get my final “compostela.” I already carried the one from Santiago, the standard from the Middle Ages still used to document and honor completion of the Camino. A second compostela was also available, showing my total kilometers, and my routes. Then I got one in Muxia, the Muxiana, having collected sellos along that track and pushed my way through the throng at the disorganized tourist office; and now, the Finisterrana. I tucked it into the red cardboard mailing tube that held all of my compostelas, which rode safely in the bottom of my pack. I loved them. I had such affection for these beautiful pieces of paper. The Finisterrana struck me as especially beautiful.

Last night after the Mass, at dinner in Muxia, having met Christoph’s lovely and charming wife,

I had mentioned them. “Where will you put all these compostelas? It’s going to be a lot of frames,” I added, and raised an eyebrow in mock distress.

“I don’t know,” he began. “We only have one real piece of art. We bought it together, when we were young – ” Christoph started to explain.

His wife interrupted. “Well, we will not be creating a ‘religious wall,'” she laughed, as if this was obvious.

Christoph looked down, and then away, as he talked of putting them in storage, in a closet somewhere.

Sad at this exchange, I changed the subject. “So – congratulations to you, on your degree! You just finished, I hear? Social Work?”

“Yes! Only just finished,” she smiled warmly.

“That’s a lot of work. Do you have any idea where you might like to find a job?” I asked.

“I have one, already set for me,” she answered with a brief nod, like a gulp.

“That’s fantastic!” I congratulated her again.

“I am…nervous? I have fear, that I do not know how to do this job,” she confided.

“Oh, of course. But you will find your way. You have studied for all these years. You could be a great social worker.” I thought about what I had said to interns in the centers where I’d worked. “The people you serve will be the ones to find their way, after all. You need only encourage them.”

I looked back at Christoph. “More wine?” he asked me, his voice dear and familiar, but his expression impossible to read.

“Yes. I’d love some.”

It had been a hard hike back to society. Climbing the hills out of Muxia alone this morning, as a rosy sun emerged, soft and quiet, I found myself in tears, not wanting to leave. I loved this place. But my Camino had ended, at the small cross on the tiny mountain; now I walked one last day, back into the world. The sun burned me, as always, and the insects left their swollen bites on my neck and legs. I had stopped to drink water, and to rest my feet. Yet tonight, I would sleep in my last albergue. And I would follow the final tradition – witnessing the sun setting over the sea, beyond the end of the world. Finisterre.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I walked the road in a haze of mist and fog. The beaches had turned chilly. I put on more layers of clothes and followed the people up the high road leading to the lighthouse. I passed a statue of a peregrino strugging uphill in the wet winds of these cliffs.

But at the top, a carnival atmosphere reigned. Booths sold trinkets and souvenirs. People toasted each other at the lighthouse bar. Mothers scolded children who strayed too far, fathers pushed strollers. Photographers set up tripods in the grass beside the path to the lighthouse.

Peregrinos, including me, stood in a huddle to take each other’s picture at the 0.00 mile marker, The Lighthouse At The End Of The World as a backdrop. This was the sort of scene I’d loved when I was seventeen. I thanked the man who took my smiling picture with my phone. A woman took his next.

I found an open patch of grass near the cliff’s edge and sat down expectantly. The sun setting in the foggy gray cast colored circles, sometimes prismatic rainbow rings, around the lowering sun. A murmur rippled through the quieting crowd, all settling in now, as we each realized what we were witnessing – an eclipse. An arc cut from the glowing orb revealed the shadow of the moon crossing the sun.

With so much fog and cloud, I looked directly into this amazing moment, happening here and also so far away, in the center of our galaxy, in our wobbly corner of the universe. I sat within those rings of light and fire, and I looked into the sun, and was not blinded.

Surreal, an eclipse at Finisterre, welcoming me back to Earth. It reminded me that the world we lived in was magical in its own right, beyond the narrow trail of the Camino. Once the sun actually set, everyone spontaneously started clapping. We applauded the setting of the sun, into the sea.

The Celts used to believe the sun died here each day, another meaning of the Costa da Morte. If it did, then tonight it went out in a blaze of glory, auras and prisms and fire and sea, a worthy Viking funeral. If it did, then it was reborn somewhere else – somewhere I needed to find. Either way, I had decided, I would be needing a boat. I hoped La Virxen was listening.

Seventeen-year-old me would be proud. She was no longer someone I had to turn to, make sure I included, make sure I listened to. She was me, right here behind the watery eyes, now with a sprinkling of gray in her hair, the lively spirit I hoped I would never lose.

After my photo, I had peeled down my layers, finally stripping off my faded, pale green tank top, paper-thin and worn and never completely clean, a color a chameleon would love, virtually invisible. All through my nearly 1,000 km of walking, I had seen tiny lizards everywhere, and had been looking for a lizard emblem to add to my walking stick.

But Saint Thomas would not accept some tokens, like the black feather that was lost, nor, apparently, a lizard. No chameleon, blending in, ever-shifting to match the surroundings, never its own true self.

I stopped at the big tent and picked up a T-shirt with the Basque/Celtic/Nordic Tree of Life on it. In “True Blue.” I went on Camino, and all I got was this lousy T-shirt, I smirked to myself.

“Is good?” the woman asked me, as I handed her my euros.

“Is good,” I smiled back, pulling it on over my bikini top, then walking away.

People were starting to kindle the traditional fires at Finisterre. You gave up something, or left it behind, writing this on paper and burning it symbolically in the cleansing flames. These fires, technically, were not allowed; therefore, they were commonplace. As I walked by one group, I asked their pardon, which they easily gave me – as I tossed the chameleon shirt into their flames and strode on by.

A cheer rose up among the group. “Buen Camino!” they shouted happily after me.

“Buen Camino, amigos,” I called back.

welcome to the end of the world

where you think you can’t go on

where the weight that you carry is measured

an ounce beneath what breaks your bones

there’s a treasure at the end of the world

but it’s not a map to gold

it’s a way to draw yourself a blueprint

with the knowledge that you hold

(C) welcome to the end of the world

lighthouse tells that you must build

a ship – let the sails unfurl

wind and waves will carry you

past the end of the world

when you’re walking to the end of the world

now you know what you must do

stop carrying the weight of the world

find a north star that is true

oh, welcome to the end of the world

lighthouse tells that you must build

your ship – let the sails unfurl

wind and waves will carry you

so welcome to the end of the world

lighthouse tells that you must build

a ship – let the sails unfurl

wind and waves will carry you

past the end of the world

— “End of The World”

February 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

this final measure

only the penitent shall pass…

“I took that pan outside, because something old on the bottom started to burn as I made my toast,” I confessed to Anna, the hospitalera in Muxia. “If you have something I can use, I will scrub it clean.” Anna had just entered the main kitchen/gathering room and noticed the front door propped open to alleviate the smoky smell.

“You would make a good hospitalera,” she smiled warmly at me. “Do you want the job?”

“Yes! But, not now,” I pointed a finger toward the ceiling, the rest of my hand palm forward in my hold-on-just-a-second mudra. “I have to finish my Camino first.”

I brought my toast and instant coffee to the table by the large windows as Anna snuggled back into her blanket on the couch, where she had fallen asleep in the wee hours of the morning. Her laptop was still open on the coffee table. We were not much beyond the wee hours now, the sun only hinting that it might rise.

Anna was a writer, too. We had encouraged each other to just take the next step, write what is next to be written. The Camino is made by walking. Now, comfortable in our comraderie, she asked my plans for the day.

“I have a gift, for La Virxen de la Barca. I need to take it to her.”

“Ah yes, will you go to the church, out on the rocks? Have you been there yet?”

“I found it yesterday,” I replied, my search for Christoph passing across my mind. “I have the Mass schedule, too.”

“I’m telling you, you should be a hospitalera,” Anna teased, rolling her eyes. “Ah, but – ” she leaned forward, “have you climbed the mountain?”

“Mountain?”

“The steep hill before the church, before you reach the sea. That is our mountain. There is a path to the top. I think you will like it. You should climb the mountain.”

So, gathering my notebook and pens, a water bottle and the Camino stone I had carried across Spain, I filled a small bag, hitched it onto my shoulder, and set off down the road in search of a mountain. Immediately before me in this tiny fishing village rose a peaked hill I must have circled, distracted, on my first trek out to the church. Here it stood, the smallest mountain I had ever seen.

The path began at steep stone steps leading up to a bell tower. The stairway split, rising on either side past the bells, ending as the stones entered the very mountain itself. Climbing the steps was like ascending a ladder, using my hands and feet, leaning into the hillside so as not to pitch over backwards. Next I scrambled a sandy, gravelly path, ridiculously steep and slippery, through thorny bushes that ripped at my legs and caught my boots again and again, so narrow and twisting was the way. I have hiked the Rocky Mountains and across the whole of Spain to die falling down a hill, I chided myself, and renewed my focus.

Just as I lost track of where the path turned next, I came over a rise and found myself at the top of the rocky mound, overlooking the endless sea. There, rising from the rock itself, stood a small, simple stone cross. It was surrounded by people’s burdens and prayers left in its care. I turned slowly, looking all around me. The morning was just reaching the boats in the harbor. Seagulls flew silently, riding the air currents circling the mountain. They did not need to call to me. I was here.

I reached into my bag. From the billions of rocks I walked over on the Camino, this one alone had caught my eye. This stone had fit snugly into the palm of my hand, had ridden in my pack with the water that sustained me every day. It had witnessed the ceremony at the top of the Hospitales Route on the Primitivo, where I threw its miserable twin as far away from me as that long-ago lonely deserted island was from this quiet, peaceful point of contemplation. Smoothed naturally by wind and water, it was heart-shaped, like a real heart, a natural heart. And it was red, the color of our blood, pumping in the good fight to live out our lives true to ourselves. The color of Santa Barbara’s dress, and of her empty tower.

I had planned to leave it at La Virxen’s chapel, or give it back to her by way of the sea. But this was the shrine I had been seeking. Alone in the new morning, I set my heart stone among the gifts of others. Thank you for teaching me how to sail my ship of stone. For the song. For finding my own heart.

Below me, the bells began to ring. I just shook my head, at myself, so hard to bless that Muxia had to pull out all the stops to break through to me; but there was no saving me from the tears that came in waves, matching each soaring intonation.

For an hour or so, I sat teary among the boulders high on the hill, sniffing and writing whenever my eyes were clear enough. The views of Muxia, and of the sea, were beautiful from that height.

this final measure

only the penitent shall pass

hands on steps

worn by prayers

bells ring our plea

two high are struck

one low is rung

two high

one low

as thorns will scratch and claw

so sand will slip your pilgrimage

but then

you rise

an echo

to stand on rock

before the sea

and gently set

like the sun

your sacred heart

upon the lichen

soft and growing

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As I came over the hill, I was once again struck by lightning. You’d think I’d see it coming by now.

Down the back side of the mountain, a path led toward the church to La Virxen. And between the mountain and the sea, between the cross and the cathedral, stood a double monolith, two massive, rectangular stones standing on end, like a Galician Stonehenge. But instead of capstones and a ring of similar structures, it was only the two stones – divided by a zigzagging cut. A bolt of lightning. Through the lightning space, I could see the ocean, rolling away to the horizon.

I didn’t fall to my knees. I didn’t need to lean against a rock for support; my legs did not weaken. Instead, I laughed like I was cheering, a long, loud exultation, throwing my hands in the air in hysterical joy. I jogged down the path in my hiking boots and walked confidently up to the enormous stones, nearly as huge as windmills. I put my hands on them, one on either stone, and felt their cool might. Then I hugged them, each one, pressing my tear-stained cheeks against their rocky faces.

I had no idea, but the Santuario de La Virxen de la Barca had been struck by lightning, on the morning of Christmas Day, a few years before I arrived. The Baroque altar, statuary, all the Catholic symbolism and gilding and ornamentation had burned. Only the stone shell of the church had survived. Only the stone walls, and the famous rocking stones attributed to her boat, perched as if landed on the stony coast – only her ship of stone survived. If you believed in that sort of myth.

The monolithic sculpture did not commemorate the lightning strike fire. It was designed as a memorial to an oil spill that happened off the coast many years before that. But the Camino provides; and as I touched the huge stones, I felt a sense of confirmation. Like the stone Roman mile marker I had passed, it felt like this was part of a larger map, helping me find my way.

Between the twin strengths of seeing and listening, writing and singing, word and tune, I would find the moments I sought. But I had to follow the paths of pilgrims, climb holy hills, search out the many meanings, layers of belief building again and again on the same solid rock. Because ultimately, the Sacred shows itself, if you seek it.

What is sacred is up to you. Give you a hint: it’s often heart-shaped.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The evening Mass was in Spanish, of course. I loved going to Mass in Spanish. Under a new roof,

I looked around at the cleaned stone walls of the santuario. At the front of the church where the ornate altar had once filled the wall, a printed image of what once was, like a massive wallpapering, covered a wooden facade. I imagined what it would look like uncovered, the power of sitting among the blackened walls where lightning had struck, setting fire to what we think will protect us from the world, and all our images.

This was my kind of church, burned but resilient, defiantly standing on just a spit of land, a wind-swept coast of boulder-strewn, wave-pounded rock and nothing more. The Costa da Morte, named for all the shipwrecks off its rugged shores. As the priest prayed, I listened to the crashing of the sea. La Mar. She who carried the ship of stone safely to its destination, bringing the sacred bones home. The Great Mother of us all. My journey had never been to Santiago.

As the service ended, I gave a euro to La Virxen de la Barca’s donativo for a candle, to light my way and send my prayer that she will continue to inspire me and guide me as I step forward into my new life. My life. Every poet needs a muse.

all the fury

of the Atlantic

cannot crush

this rock of me

February 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

seagulls

hadn’t realized

how much I missed them

until I heard their voices

calling me home again

Jerome and I hiked downhill through a forest of pine. The sweet smell and softness of the needle-covered path under my feet reminded me of home. Suddenly he stopped, and said, “Listen.”

I could hear the waves, crashing on a shore beyond the forest, the surf like something alive and breathing. We continued walking through the densely forested hills, listening to the ocean we could not yet see. Finally, we stepped out of the forest, and – there it was. The sea. I was back to the sea.

Excited to arrive, with only a few kilometers left, we walked happily across a road toward the direct path to Muxia, and – there she was.

Joanna.

Unbelievably, without missing each other by a day, or an alternate route, or a coffee break, we met again on the path.

We screamed! We screamed with delight and joy, relief and wonder. What a fantastic surprise! What a gift. Joanna, who taught me affection, was hugging me tightly again.

She kept saying, “I knew! I knew! We thought you would follow behind us, but I KNEW I would see you!” With many friendly kisses, she insisted I come visit in Poland, and I agreed, I must. We took photos, and Jerome took photos of the two of us together, hugging and laughing.

Then, with a shock, she said loudly, “Oh! You must go!”

“What – why? We just found each other!”

“No! You must go! Christoph – he is in Muxia! His bus leaves at half-past two – go to him! Go to Christoph!”

Go to Christoph. I could not believe it. I didn’t want to let Joanna go, but she hugged me again, and said, “This is the miracle,” her lip trembling slightly at the mysterious ways of the God she loved. She nodded firmly. “You go.”

Buoyed by the wonder of Joanna and her thrilling news, Jerome and I walked easily to Muxia by 1:00pm. I anticipated a real goodbye with Christoph, and vowed to myself be honest in every moment, nothing more. Checking in at a private albergue – first bed available – I went to look for Christoph by 1:30. I had an hour.

I checked the two bus stops in the tiny village. I checked the seaside promenade. I checked the tourist office. I stopped to think. Where would I find Christoph? The church. I walked out to the church of La Virxen de la Barca, checked the crowd on the plaza in front, checked inside. It was approaching 2:00.

Knowing him, he would be at the bus stop early, so I went back to wander the outdoor cafes nearby. There sat his familiar figure, back to me, carefully watching all the new pilgrims entering town. I walked up and sat in the chair beside him. Christoph turned.

“Hey!” We were smiling and laughing. While I had been looking for him, he had been looking for me, in the cafes, along the sidewalks, now watching for me to arrive. I had just missed him at the church by 15 minutes.

“Joanna said you are taking the bus?” I asked.

“Yes, back to Santiago. I will meet my wife’s plane.” She was joining him, coming out to see Muxia; it seemed he had contacted her and arranged this at some point recently while he journeyed. I was surprised, and then not surprised.

“After I left Santiago, I had a couple of hard days,” he shared. I wondered what all he had been struggling with, if I had been a factor among many, but I didn’t interrupt. “Now I have made peace with these struggles,” he concluded, and I felt the distance from him as I smiled, familiar with this trick to set a difficult boundary; we had talked so much about it, and now I could plainly see it.

“I want to thank you so much, Christoph,” I countered. “You were key to much of what I learned on the Camino, because we did our intellectual ‘sparring,’ you know? To measure each other’s minds.”

He laughed. “We use it to create distance.”

“I agree. To hide.” I looked past the invisible wall. “It let me respect your opinion later, however; when we talked, I could hear good points you made, that I needed to hear.”

“I…was not that important to this,” he protested.

“You were. I could hear this, only from you. Thank you.”

His wife had just finished her internship for her B.S.W. – her degree in Social Work. She had just finished it, and was arriving the very next day, to celebrate, with Christoph. It dawned on me that this was not the original plan, that when he said he left at “just a terrible time,” that the timing of his Camino “was the worst,” I could see the strain he had placed on her, how his Camino had potentially sabotaged her success – or ignored it. Unenthusiastic, disinterested…absent.

Five long years to make a CD. I felt for them both, as they tried to repair this choice and its effects.

I said, “Don’t go,” in our half-joking way we had used before, which of course meant, Don’t go yet, because I’ll miss you.

He surprised me. “We will be in Muxia tomorrow night – we could meet up, if you wanted to. Will you be here?”

“Yes, I can be, easily. I have no timetable.”

“I think you will like her,” he said earnestly.

“I want to like her, Christoph. I do. I want you to be happy in your life.”

As we waited for the bus, I told him about adding a new image to my walking stick, made from a red string I found, already knotted and shaped. “Over a broken place on my stick, I have tied a Sacred Heart, with an X like crossed arms, embracing it.”

“Really!” he responded, like he always did.

“Yes. It is the Sacred Heart of Santa Barbara, I believe.” I gave him a satisfied smile.

He grinned his huge grin and whooped, “Yes! We love our Santa Barbara of the Camino!” And as his bus arrived, we hugged, a huge, tight hug.

I said, “I love you, Christoph.”

“And I love you, Barbara.” We stood back in our embrace, smiling at each other. “See you tomorrow?”

“See you tomorrow.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

So much more, we said. I talked about how my first two husbands cheated on me, got girlfriends, and how painful this was to my heart. We agreed, we had both been cheating – on ourselves.

I called it “this longtime dalliance with social work instead of writing and music,” and he immediately understood, saying, “Yes, it is the same for me.” This feeling of being understood, this is what I fell in love with.

As Jerome had told me, damaged children, they believe no one can ever understand them. This is the great prison – ALONE, always. It is not freedom. It is a deserted island, with no resources, barely surviving until you die. It is no island paradise. It is a torture.

In his work, they taught the children that their feelings were the key to being understood. Being able to feel, and to name what you feel, allowed you to give meaning and context and weight to your thoughts and experiences, so that others could understand what you meant. So that others could understand You. “We teach them that of course they can be understood.”

Jerome spoke of the danger of children becoming chameleons, changing to be whatever is acceptable. We talked of buying acceptance and a fragile peace, a threadbare security, through good grades or best behavior or other, terrible prices to be paid.

And I remembered Christoph’s comment to me: “I hope one day to be free as you are, Barbara.” And the word Joanna used: “I feel free when I am with you.”

Sitting at the cafe table, overlooking the harbor in Muxia as the bus to Santiago drove away in the distance, I considered the possibility that I had beaten the odds, escaped the shadows. That I was among friends who understood me, and had been, all along the Camino. I no longer had any need to hide myself away.

I didn’t need to be a chameleon of duty, or romance, or approval, but simply me. At home in the world, writing, and singing, and loving people. Able to make myself understood, and so, able to make connections.

Free.

I sat watching gulls swoop over the water, as the sun dropped lower and lower in the sky, then wandered home, to the albergue.

what – are – you looking for

and what – are – you finding

you talk – like – you’re always sure

but you look – like – you’re hiding

And I just have to ask – what is sacred

I just have to ask – what is sacred

I just have to ask – what is sacred

to you…

(I just have to ask)

if you – lost – all you have

what – would – you have left

if you – lost – your camouflage

where – would – you hide next

And I just have to ask – what is sacred

I just have to ask – what is sacred

I just have to ask – what is sacred

to you…

(I just have to ask)

— “What is Sacred (The Chameleon)”

February 9, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

As Gorma passed through a small village on a steep hillside, she paused at a fountain to refill her water jug. She heard the laughter of happy children, and turned to see a class of children and their teacher all walking from the nearby school to the tiny library on the corner near the fountain. As the teacher smiled, Gorma saw a gap between her front teeth, and called out to her.

“So you have received the Holy Kiss?” Gorma asked the teacher, who smiled again, and turned to hug Gorma in a warm embrace.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, what are you talking about now?” she asked. Her name was Joanna, and her hug warmed you like a blanket on a rainy night.

“You do not know the story?” Gorma asked. “I will tell you. But first, tell me, how does such a small village have so many happy, eager students?”

“Ah, that is easy. This is the School for Brilliant Children. I am their lucky teacher,” Joanna replied smiling, and Gorma saw the gap between her front teeth again.

“I see,” said Gorma, taking a long drink of the cool fountain water. “And how are the children chosen for this school?”

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, that’s easy,” Joanna answered. “All children are brilliant. So of course, they are all chosen.”

“And what if some have difficulties with the school work?” What if some of the children struggle?” Gorma asked.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, they all struggle!” Joanna laughed now, and her laughter was like a happy song. “If some have need of extra help or understanding with the learning, then we spend time reassuring them, each one, that they can learn, that they can communicate their questions and their feelings to us, and we can understand each child, and how they learn best. We show them their brilliance, like holding up a mirror for them to see themselves, clearly.

“But what if they have other struggles?” Gorma asked. “What if they are sad?”

“If they are learning just fine, but have other sadness, or fears, or anger in their lives, then they come to me, and I let them talk, or draw, or craft in clay, each one, until they see their feelings there before them, made into a work of art. Until they see that they are brilliant children carrying heavy stories, is all. Often, brilliant children must also be strong children.”

Gorma took another drink from the fountain. “And how do you teach lessons in your School for Brilliant Children?”

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, why games, of course! Children learn through play, so we have counting games and spelling games, garden play and cooking play; challenges for running like a horse and swimming like a fish, and challenges for sitting very still and quietly, like a butterfly, or singing sweetly like a thrush while perched in a tree. And always, we have laughter, and smiles, and hands to hold, hugs to share. It is a busy day of learning, and a happy one.”

“Yes, it is quite clear you have received the Holy Kiss,” Gorma nodded, pleased.

“Are you talking about this gap in my teeth again?” Joanna asked, shaking her head and laughing like an angel.

“Indeed I am,” Gorma answered. “It is said that this gap is where the Spirit of All That Is Sacred passed through as the Breath Of All Life, bestowing this Holy Kiss upon you with the air you breathe.” For Gorma knew it is in the tiniest gaps, the small moments of space and time allowed to us, that we find the sacred, within life, within others, and within ourselves.

At this, Joanna hugged Gorma tight. Tears came to her eyes. “It is only the fact that each child is brilliant,” Joanna protested.

“It is only the fact,” Gorma countered, “that you give each brilliant child the space to shine.”

Then Gorma smiled back at Joanna, and sent her on her way to retrieve her students from the library, where they had each found a book of interest and wonder to carry with them. They all filed past, back to school, happy and laughing, each with a friend beside them.

Gorma walked on, quiet and smiling, and arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. Outside, the brilliance of the stars was so bright, all the darkness of the night glowed with billions of possibilities.

Buen Camino, Joanna.

February 7, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

- Take the ever-present, albergue kitchen open bag of stale pasta.

- Boil some.

- Having bought a bottle of cheap red wine, drink some. Share with everyone.

- Use the half-bottle of tomato sauce or half-bottle of diced tomatoes or half-bottle of tomato anything left at the albergue.

- Add your pate negro, which is beef? liver? pate.

- Add any leftover olives from the fridge. They’ll be located next to the dried out mustard.

- Bonus Points! if your albergue has any spices.

- Add a LOT of wine to your sauce.

- Pour sauce over drained pasta.

- Scoop out the last of any soft, canned cheese you have leftover from lunchtime. Mine was camembert. Plop dollops on top.

- Eat with your very dry bread dunked in the sauce.

- Again – share with everyone. This is what makes stale pasta so delicious.

- Finish the wine. ¡Salud, peregrinos!

February 6, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

everything

is the ocean

ebb and flow

cupping water in my hands

and splashing it on my face

like I did

to taste the sea

gulls of memory

always rising

The morning dawned gently, the sun rising on softest feet across a sky warmed by woven, woolly clouds. I walked the dirt path as quietly as I could, like a mother tiptoeing to the kitchen past the doors of her children’s rooms where they lay peaceful among their last dreams before waking.

Sheep grazed beyond the heather alongside the Camino, snug between a cornfield on one side, an old stone church walling the other, its bell hanging still and silent. A mist rose from the valley, washing over me as I strode along the high hilltops, then receding like a wave back from the shore.

When the fog finally lifted, there stood the windmills at last. I had attempted to photograph them each time I encountered them along the entire way, but until now, every opportunity had been thwarted by mist and fog. At one point, I walked a trail directly beneath the moving monoliths, but hidden in cloud, I could only hear a low, rhythmic rushing, the regular thump of their blades pulsing through the wet air, like the heartbeat of someone holding you close to their chest.

I wanted a picture of the windmills for Magnus. Before I left, we had watched a movie about the Camino. He thought the windmills were cool, impressive, and he would want to see them if he came to Spain. Now at last, I had them before me.

The thing I couldn’t capture was the perspective. I could see they were massive, but what my eye saw and what my photos showed were two different things. My pictures could not portray the enormity of the hills leading to the coast, or the power of the windmills, or the rolling of the thick clouds throughout the day. Photographs could not begin to match my experience of the Camino. More souvenirs. I would have to tell him stories, to explain.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Not far past the windmills, I came upon another small church, surrounded by an elaborately walled graveyard, all of this stepped down into the earth itself, terraced into the side of the hill. Nearest the Camino, a tall, stone pillar topped with a crucifix, a cruceiro, stood in a grassy yard,

a small, lichen-covered stone bench beneath it facing the church, and the mountains, and the graves. Best seat in the house, with a view of eternity. I read the sign: San Cristovo de Corzón. Christoph of the Heart. Unbuckling my hipbelt, I took off my pack, and set it on the ground.

Sitting on the small bench, I thought about the windmills hidden in the clouds. I thought about the sound of heartbeats, heard even from far away, or with your ear to the chest of one you love.

Sitting on the small bench, I thought about the windmills hidden in the clouds. I thought about the sound of heartbeats, heard even from far away, or with your ear to the chest of one you love.

I thought about the Plaza do Obradoiro.

I tipped my water bottle, tasting the faint residue of iodine from weeks before. Having been in Spain for over a month now, I no longer fastidiously treated my water at every refill. I had adjusted, like acclimating to altitude; I could drink the tap water like a local now. I could trust the world to sustain me.

I drank another long swallow, and sat looking at the wall protecting the cemetery. Stone angels stood at the peak, facing each other. Beyond them, crosses lined the top of the wall, stretching away toward the mountains, toward the sea. The pattern repeated over and over, like the far-off windmills spinning their blades in the strong winds that kept rolling the clouds beyond me.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I ended my day walking with a young man named Jerome, from Germany. He was a social worker employed at a children’s home that was more like a fairy tale camp. He described the small timberframe houses on a hillside as “like the setting of the story of ‘Heidi’ – you know this story?”

Jerome usually walked very fast, and very far, but he fell in step with me as we talked, and so we arrived together in Dumbría. He asked if we could walk together again the next day, to arrive in Muxia together, and I agreed, because the conversation was interesting and meaningful.

The children sent to live at Jerome’s site were temporarily removed from their homes as part of a larger plan to eventually reunite the family, if at all possible. Jerome insisted that his job, as well as that of most of the staff, was simply to be an adult role model, offering safe relationships and consistent caring regardless of the child’s choices or behaviors. The child’s point of view was not only accepted, but respected. The child was valued, taught that they had value, because they usually arrived abused or neglected, feeling broken and invisible, worthless. This typically changed over the course of the 1-2 years of their stay in the picturesque Heidi village. A healthy self was found and cultivated. A “You” was nourished. They emerged, blossomed.

In Dumbría, I walked to the tiny market in the back of the bar down the road. I found a few items, an apple, bread, cheese. I took them to eat beside the local stone church, Santa Eulalia Dumbría. Saint Eulalia was only 12 or 13 years old at the end of the third century when she was tortured to death for believing in a God that loved her.

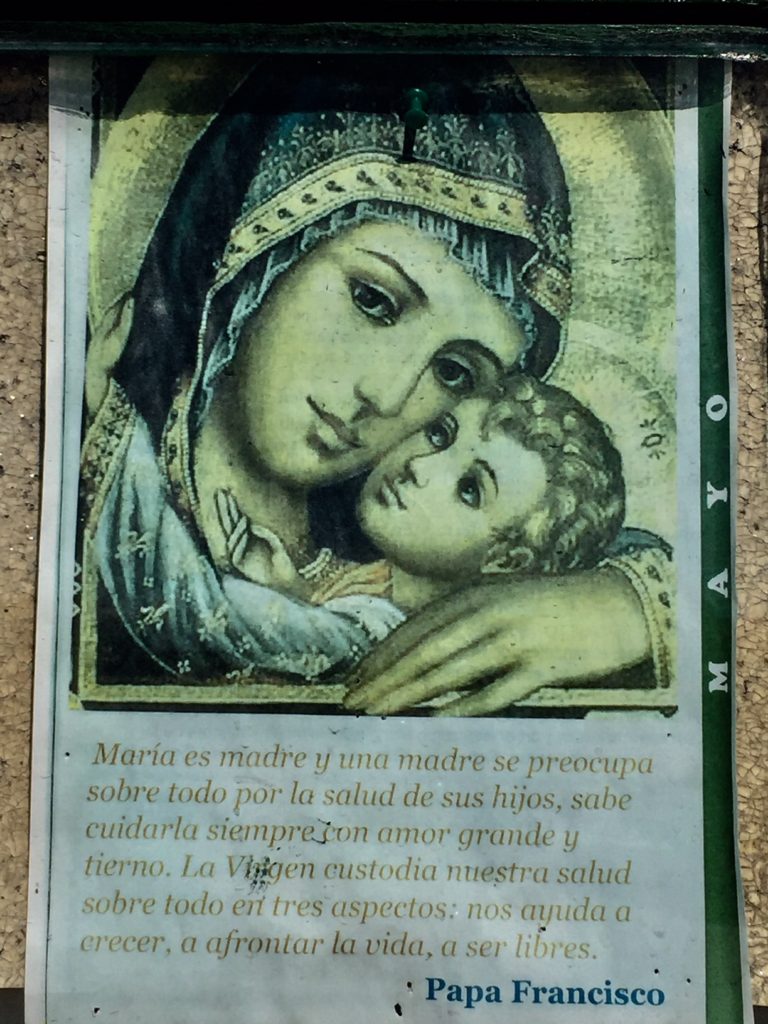

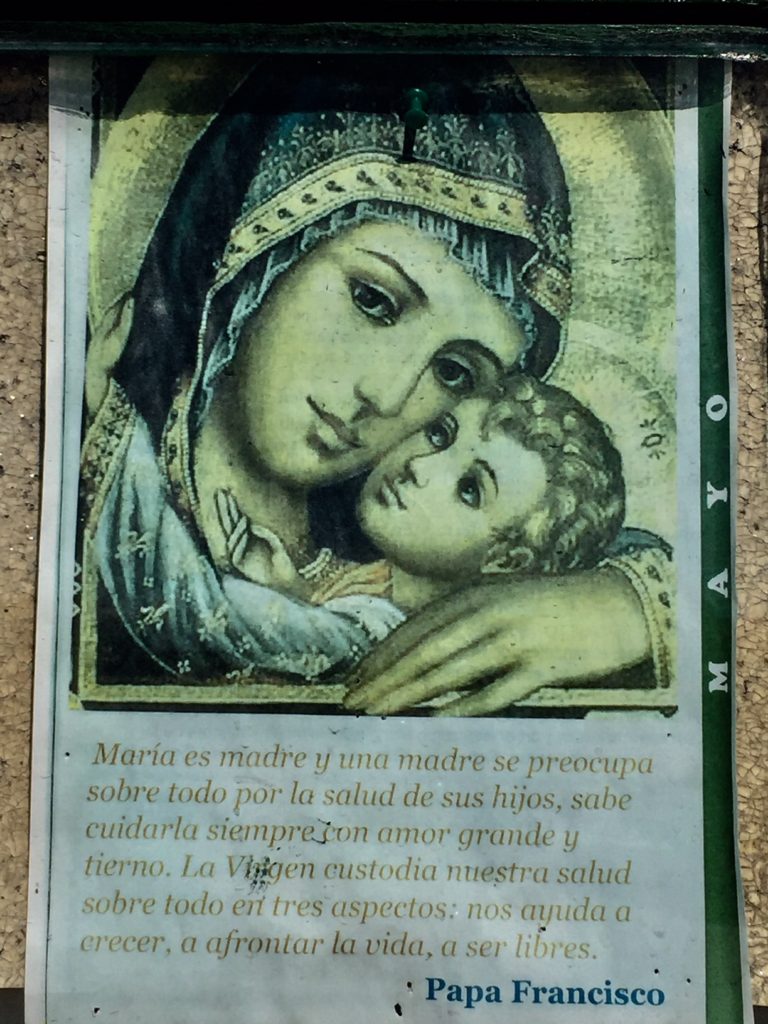

I compared this story to a poster hung beside the door to the church, reportedly a quote from Pope Francis:

“Mary is a mother, and a mother cares above all for the health of her children, knows how to take care always with great and tender love. The Virgin keeps our health above all in three aspects: helps us to grow, to face life, to be free.”

As I looked at the face of La Virgen, I silently hoped Magnus was receiving these intended gifts of great love. It was part of why I had come on Camino now. And why I still carried lingering doubts, my walking stick Saint Thomas still marking the Camino with every step.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Next morning, I set off with Jerome in a light drizzle that soon ended. Our stops were brief, and we made good time, having found a compromise pace between our two extremes. Our conversation returned to social work, and parenting, and soon we talked of Magnus.

I loved Magnus’ father. When it quickly became clear that he had been wildly idealistic about step-parenting four other children, including teenagers, and was overwhelmed and out of his bachelor depth, we separated – but now we had a baby.

He was wonderful with the baby. He adored Magnus. He watched the baby during the week, and I took him on the weekends. I promised him I would never take Magnus away from him. But I couldn’t promise that Magnus wouldn’t step away himself – which he did, at the beginning of high school. He asked to come live with me, for two years, while he and his dad worked on their relationship on the weekends.

Nothing about Magnus had been my idea, except his name. His father had so wanted a baby; I was resistant, having four already. But love often steers us to sail the seas against our better judgment, under thick, rolling clouds, in a ship of stone that can only reach the farther shore by a miracle. In love, I agreed, but added, “You have to be the one to take care of this baby – because I have things to do.” I had already put my creative work on hold for years; I knew starting over, a new child, would delay this work for years again. And I couldn’t bear it any more, the waiting.

I had already begun to write songs again. Finally. I had met Magnus’ father when I went searching for a guitarist – I found both in the same month. So as my belly grew, I sang. Holding an infant in my arms, I sang. Dropping him off at his father’s apartment, I went back to work, and once every week, after work, I drove out to the studio, and I sang. And when at last I recorded a CD, and my guitarist handed the master to me, I went straight to that apartment so Magnus’ father could hear it.

I knocked at the door at 9:00pm. Magnus was already in bed for the night. His father opened the door, and I jingled the CD case like a magic wand in my hand. “It’s done!” I said, excited. “Want to hear it?”

An odd pause filled the open doorway. “I’m…pretty tired,” he replied.

“But – it’s done – don’t you want – ” I faltered. “Ah, okay,” I managed. I turned and walked back down the stairs. I don’t know what else was said. Maybe we agreed to listen to it later; maybe he just said goodnight. I didn’t even care why he hadn’t let me in – maybe he was actually tired, maybe he had a woman over, who knew. The reason didn’t matter. He had shown no enthusiasm, no interest whatsoever. It was as if my guitarist was “the other man,” as if my songs had broken us up somehow, not our ill-conceived relationship itself.

The CD had taken five long years to complete. His response broke my heart. Magnus was starting school soon. I was done.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In The Artist’s Way, author Julia Cameron describes a creature called “the shadow artist.” This person is a creative spirit as well, but quashes that spirit in themselves and those around them, even as they are drawn to other artists like a moth to that holy flame. Theirs is a resentment based in fear and longing. It is the love-hate of a deep wish to rise into that light, tied like a heavy anchor to an expectation of failure which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

My mother had been such a creature. Now I had another in my midst. Magnus’ father was an artist who sold off all of his tools, gave up on creating, and now bought and sold everything and nothing online. He barely got by, a starving artist who no longer made art. I had chosen a tie that bound me to my day job, my desk job, the steady paycheck security of hearth and home.

But when I looked at Magnus, I was torn. Here was the creative spark of two artists, joined in one soul. One beautiful, musical soul. I vowed I would not remain in the shadows. I would teach him about the light.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

“Are you sure you’re not making a mistake, sending your son back to his father?” Jerome asked as we marched steadily along the road.

“No, I’m not sure. But it’s what he wanted, to go back to his dad’s, his hometown. They’ve been working hard on their relationship, I know that. So we’ll see, at the end of this summer, how it’s going.” I had offered this “out” to Magnus before I left, deciding I’d figure out a Plan B if it was needed.

“But is it the child’s responsibility, to determine what is best for him, what he needs?” Jerome continued. “Are you choosing based on the needs of the child, or for the father, what the father wants, and your love for him?”

I thought about my promise never to take Magnus away. But I never promised Magnus couldn’t choose for himself. “Sometimes I do forget how young Max is. He’s just starting his junior year, this week, actually.”

He had the sense of humor of his older siblings…he kept up with them in conversation. Ready or not, he was about to make life choices, apply to college, enter the world. It was easy to forget how young he was, because he tried so hard to be mature. He also fought for respect with a fiery temper and a fierce pride; I was not confident I could dissuade him from any choice he decided to make, once his mind was made up.

“I hope I am focusing on him in this decision. I believe I am.”

I had known my travel would be hardest on Magnus. For the first time, I was stepping away from him for months, not days. But I also knew, just as clearly, that I had to do this. I knew the timing appeared terrible for his life; I knew it looked disruptive. But I was at an imperative in my own life: the dissonance of who I had always felt myself to be, and who I was being, was so uncomfortable, so painful, I had to resolve it.

Whether Magnus fully understood it or not, I was rising up. I saw clearly that he was fast approaching the age when I had disregarded my own dreams. I would raise my self-doubt like a lance, to show him how windmills and their patterns of shadow were defeated. What appeared to be giants were simply not so.

I glanced at Jerome. I trusted the dreams of adolescence, with everything inside me. I believed Magnus was the only person to decide what was best for him. My job was to encourage him to dream, well and true to himself, and help him to grow into that self, to face life, to be free.

I would show him how.

“Now look, your grace,” said Sancho, “what you see over there aren’t giants, but windmills, and what seems to be arms are just their sails, that go around in the wind and turn the millstone.”

“Obviously,” replied Don Quixote, “you don’t know much about adventures.”

— Miguel de Cervantes

the best words anyone gave me before you

were you’re gonna be all right

you’re gonna be all right

the best words anyone gave me before you

were you’re gonna be all right

you’re gonna be all right ….. all right ….. all right ….. all right

the best gift anyone gave me before you

was how to sing the stars

shining where we are

the best gift anyone gave me before you

was how to sing the stars

shining where we are ….. and we are ….. all right ….. all right

the best touch anyone gave me before you

never lasted long

before it all went wrong —

but on that plaza of gold

where the cathedral bell tolled

like a bell our laughter’s sound

you swung me round

you swung me round

you swung me round

the best words anyone gave me before you

were you’re gonna be all right

you’re gonna be all right

the best gift anyone gave me before you

was how to sing the stars

shining where we are ….. and we are ….. all right ….. all right ….. all right

we are ….. all right ….. all right ….. all right ….. all right

— “All Right”

February 5, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

Gorma sipped her coffee in the darkness, and waited. The sun was about to rise, and as she sat on the wooden bench on the front porch of the albergue, she held the warm mug in both her hands, cuddled into her warm wrap. Then she heard it – the soft but clear song of the first bird of the morning. Gorma smiled and sipped her coffee again. This was her favorite time of day, as if she and the first bird were the only ones awake in the whole world. It was a close and cozy feeling, and sounded like a brand new song every morning, a song the bird sang only for itself, a song of its own happiness.

As Gorma sat listening to the other birds joining the chorus, a most handsome and graceful man stepped out the door of the albergue and sat on the bench beside Gorma.

“Good morning, Gorma. I have brought more coffee, and fresh croissants, if you would like a little something for your breakfast,” he smiled, and his smile lit up the porch like a lovely candle. This was Bruno, who was traveling from France, “in search of beauty, only beauty,” he said, in a voice so musical it made Gorma want to sing.

“How will you know when you have found beauty?” Gorma asked between bites of flaky, chewy croissant.

“I am from París,” Bruno replied, wide-eyed. “Beauty will find me, and we will recognize each other, with joy,” he smiled again, bowing his head slightly to the right, which turned his smile to enchantment.

“Ah, yes, of course,” Gorma answered him. “Thank you for my breakfast, Bruno,” she added politely.

“Thank you for sharing this sweet morning with me,” Bruno offered in return, and as he turned back to the albergue door, all the birds burst into song together. Bruno paused for a moment, listening, then smiled his magical smile, and slipped inside to the kitchen once more.

Gorma walked all day, down many paths and roads, and saw many sights and wonders, including an inchworm slowly inching its way across a dirt path, and a hillside of wildflowers shining in the sun. At the albergue that night, she again saw Bruno, and he offered her a seat at the table.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, still I am in search of beauty, only beauty,” Bruno sighed, dipping his bread into the delicious soup served to all the travelers at the albergue.

“Did you see the inchworm crossing the dirt path, or the hillside of wildflowers that we passed today?” Gorma asked between spoonfuls of soup.

“An inchworm? A few flowers in the grass? Beauty, Gorma, beauty,” Bruno said, shaking his head, wide-eyed. “But I know, beauty will find me, and we will recognize each other, with joy,” Bruno smiled, and the last rays of the evening sun through the albergue windows turned his smile golden, so that everyone at the table turned and smiled, as well.

The next day, Gorma again walked many paths and roads, and saw more sights and wonders, including mist rising from the river, and tiny lizards darting up and down a warm stone wall. At the next albergue that night, she again saw Bruno, who was walking among the tall trees. He was drinking water with lemon, and offered some to Gorma.

“Oh, Gorma, Gorma, still I am in search of beauty, only beauty,” Bruno sighed, drinking the last of his icy cold lemon water, prepared by the albergue host for all the weary travelers.

“Did you see the mist rising from the river, or the tiny lizards on the stone wall we passed today?” Gorma asked between refreshing sips of bright, lemony water.

“Mist and fog? Lizards? Beauty, Gorma, beauty,” Bruno said, shaking his head, wide-eyed. “But I know, beauty will find me, and we will recognize each other, with joy,” Bruno smiled, and as he did so, the birds in the trees before them flew to Bruno, encircling his head with their wings, and singing their last songs of the day. They rose into forms of flowers, and curves of inchworms, flowing like mist along the river, and then darting away like the quickest lizards.

Gorma was amazed. “Did you see, Bruno? Did you see how you have charmed the birds? Oh, how they rise and sing for you!”

But Bruno waved his hand, as if waving away a gnat. “Birds, birds,” he said, kindly, but unimpressed. “Beauty, Gorma, beauty,” Bruno said, smiling, and again the birds sang one last chorus of their song, just for Bruno.

“Sometimes, we are so accustomed to beauty, we forget the joy we once found in recognizing it,” Gorma replied thoughtfully. Gorma knew that a shining life can often blind us to the ordinary magic swirling around us each moment. She looked up now. “Bruno, would you please have coffee with me tomorrow morning, as we did a few days ago?”

“Gorma, I would be delighted! Shall I bring pastries for some breakfast, too?” Bruno added enthusiastically.

“No, no, just a warm mug of steaming coffee, one for me, and one for you,” Gorma directed. “We will meet when all is dark, and all is quiet, just before the sun rises, out on the porch of the albergue.”

Bruno looked at Gorma wide-eyed, then softened, adding, “As you wish. Until then, dear Gorma,” and with a wink, Bruno turned and went inside to bed.

The next morning, Gorma sat on the wooden bench of the front porch of the albergue. It was still dark; the sun was about to rise. Very quietly, Bruno stepped out the door of the albergue, two steaming mugs of coffee in his hands. He gave one to Gorma and sat beside her. He was about to speak, but Gorma lifted her mug and nodded, and so they both sat in the quiet darkness, close and cozy, sipping their coffee.

They held their warm mugs with two hands, and cuddled into their warm wraps. And just as they were warmed and content, they heard it – the soft, clear song of the first bird of the morning. Bruno lowered his mug and listened again, to this brand new song of a brand new day, the song the bird sings only for itself, the song of its own happiness. And Bruno smiled, with joy.

Gorma walked many paths and roads that day, just she and Saint Thomas, her walking stick, quiet and smiling. She arrived at the next albergue just in time for a bed, for which she was very grateful, and she slept deeply. Outside, the night was still and silent, as if holding its breath, waiting for the sun, and the song of beauty that is the song of each new day.

Buen Camino, Bruno.

February 5, 2018 / wanderinglightning / 0 Comments

I recognize you

Ocean

so hard

to understand

I walked, meditating on the stars in broad daylight. To be exact, I was mulling another line I remembered from that horoscope I’d clipped from the newspaper years ago, a line assuring me that when the circle was broken, I would find “three big, beautiful truths that have been staring you in the face.”

So I continued today, puzzling over meaning found in that long-ago voice from above, that singer of celestial prophecies. My mind followed my footsteps, wandering across the winding kilometers.

I thought one truth might be my connection to music. Magnus had asked me about it one day, saying, “Why did you stop playing? Why didn’t you do anything with it?” I didn’t know exactly. The answer had to do with twisting music into work, as if any regular, singular pursuit would remove it from the realm of art and force it into a resentment that would break my heart. That, and I had completely broken down as I started college, my solid strength melted like magma in the volcano of my exploding fury. That vulnerable heart of music had barely survived. I had barely survived.

But I had survived, lived to tell the tale, to speak the unspeakable. A second truth might be that I was a writer; still, the line between poet and songwriter was virtually indistinguishable in my mind, and it seemed a bit too neat for the Three Truths to be the creative tasks I took on. If I filled the third slot with this spiritual journeying, walking the pilgrim’s way, were those the Big Three? What about my kids? They were a huge Truth in my life, a powerful healing influence for sure. Or all those homeless men and women I had met, who talked with me about the meaning of our existence, the mathematical absolute value of a human life. Talk about Truth.

This walk was sola, today’s Camino. Every day’s camino, in truth, I thought. I knew this traveling, this spiritual road I was on, informed who I actually was. It wasn’t just “interesting,” or fun. I recognized that it was integral to my true self. I was born a peregrina; to walk camino was my Way. This much I knew was true, beyond any doubt. I was born under a wandering star.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I took a detour. An alternate route led along the river out of Negreira, a beautiful, green meander. Muy tranquilo. I was captivated.

I say yes and ever yes whenever the distant, unknown, and beloved beckon me.

— Kahlil Gibran

I was all about detours and beckonings. Yet I nearly skipped the river path, thinking to stick to the main trail…not get lost. But I was saved by a Tolkien T-shirt slogan: Not all those who wander are lost. I took the turn.

For years, I had stayed the course, keeping the same job, living in the same house, wedding myself to external stability in hopes of mitigating the emotional instability of my relationship choices. It had been a spiritual instability, I saw with new clarity. I hadn’t known what I believed in. I hadn’t even truly believed in myself – I believed in only one small trait, my ability to gut it out, my toughness, driven to carry my load without complaint, pushing forward, always pushing ahead through whatever swamp or quicksand I found myself in.

The texture of rivers is ever-changing. Little rapids poured riffling and bubbling over smooth stones and submerged limbs. I watched this flow into slower pools, deep purples and indigos of shadowy hiding places, imagining I saw a ripple of fish below, life moving beneath the surface. Tall, thin trees swayed above these mysteries, guardians of the waterway as well as nourished and fed by it. Sunlight was ushered quietly through the leafy canopy, dappling the paths of both fish and pilgrim, slowly journeying side by side.

It still appeared that the Camino waymarking worked best if I would go to Muxia first, and then Finisterre, so I had changed my plan. Go with the flow, I decided. I was hoping most people were headed to Finisterre and I could continue to enjoy my solitary hiking; so far, this route had been the least crowded of all.

The river opened out into a watery clearing. All was green – algae, duckweed, lilypads, water, trees, air. My eyes, a watery turquoise of green and blue, reflected on the stillness. Reflected, without and within. I wondered how I would return to the world I had known. I saw that I wouldn’t…not in the same way. Not as the same person.

And not yet. Not today. Today, I was coursing downstream. I was in the Flow.

The river is everywhere.

— Herman Hesse, “Siddhartha”

For me to write, I needed to relax my mind. Mentally roll my neck, flex my shoulders, breathe. To write a poem, I needed to get past the surface image, see within some experience. To write a song, on the other hand, I found I needed to listen, intently. Visual art often stimulated poetry within my mind, and I frequently created collaged paintings that included poetry. Songwriting, by contrast, was somehow a process of wave and motion, tuning in to sound waves I heard by listening with my presence rather than with my ear, while moving myself within time and space, as if I was the radio dial. I was quite literally the receiver.

To write the songs I sang, I needed to access both poetry and melody. It was a unique combination, this tuning in, always accomplished solo. The irony of that word, this performance of the individual, was not lost on me. I needed to go on a ramble, by myself, to create. I needed to let go of any destination, and just explore.

Don’t push the river.

— Barry Stevens, Gestalt therapist and author

Wandering was my gestalt – the whole was so much greater than the sum of its parts. What I gained from following my feet was a camino of creativity, an openhearted art studio I carried within me. It was a watery stream, this path. Because of this fluidity, I found a grace in following it. Grace along the Camino, a flow of forgiveness and love that I had not expected or even sought; like dancing with Magnus down the hills, my pain relieved, smiling, humming a tune.

The only way to make sense out of change is to plunge into it, move with it, and join the dance.

— Alan Watts

I wrote three songs before I reached the albergue for the evening. Months later, I would learn that, while I was singing down the Camino, scientists had been discovering two streams of stars flowing within the halo of the Milky Way; they described them as rivers of stars, flocking like birds around the core of our galaxy, flowing their own way through the Via Lactea. They would find more.

river flows

gently arcing as she goes

river flows

and she’s talking to herself

sings a little song

river flows

never staying in one place

river flows

and she’s wandering away

gotta be moving on

you know, the river she can see you

you know, the river she’s not blind

though you think that she will free you

she was only being kind

and so the river flows

river flows

on the surface she is glass

river flows

she will show you to yourself

revealing nothing more

river flows

current carries her away

river flows

in a love song to the sea

it’s where she wanna be

you know, the river she can see you

you know, the river she’s not blind

though you think that she will free you

she was only being kind

and so the river flows

— “River Flows”