much obliged, pard’ner

Indulgence: remission of part or all of the temporal and especially purgatorial punishment that according to Roman Catholicism is due for sins whose eternal punishment has been remitted and whose guilt has been pardoned (as through the sacrament of reconciliation).

— Merriam-Webster

As I strolled toward Lugo with a young Frenchman named Fred, we passed through a tiny village, or maybe a large farm; it was hard to say. A huge tree stopped us in amazement, so old and so much a part of the place that the usual stone wall was built right into its massive trunk, the gate attached to its other side.

As we stood marveling and discussing the age of such a tree, a sweet dog and a puppy came out to greet us. The dog took a soft head rub from each of us and, tail wagging, trotted back to the nearby house; but the puppy had recently gotten its new, sharp teeth, and kept playfully attacking our ankles. Fred laughed in fond delight, until the naughty puppy quickly nipped a hole in his sock, so that Fred shouted in surprise and shooed it away with his hand as he assessed the damage. The pudgy little ball of energy then pounced on my foot, untying my boot lace. We dissolved into hilarious tears of astonished laughter as we tried to walk, first one of us with a puppy on our boot, then the other, runny the furry gauntlet of one determined little canine toddler, until the puppy finally got tired and we made our laughing escape.

At the beginning of the Camino, I had read in my guidebook about loose dogs, especially on the Primitivo, and strategies to defend yourself from them. I had planned to buy dog treats, but at each market, if they had any at all, they came in bags much too big and too heavy to be of any practical benefit for a pilgrim. A ploy was just a burden, it seemed.

Nevertheless, I had now survived my run-in with wild Primitivo dogs, armed only with indulgence. The Latin origin of “indulgence” meant to be kind, tender, an aspect of coddling, and babying, which all led back to mothering.

When Fred joined me in my slow walking, I couldn’t help but notice I seemed to collect quite a few young adults along the Way. Fred, Felix, Francesca, and also Jana, eighteen and brand new to adulthood, and the two young Japanese girls who had no English or Spanish, but waved and smiled whenever they saw me, sometimes gesturing at crossroads, their faces asking the question until I pointed them in the right direction, showing them an arrow farther ahead and receiving their reassured expressions and deep nods as bows of appreciation in return.

All the ages of my own children, I enjoyed our talks about the meaning of the Camino, why they had come, and what significant life choices awaited them when they returned home. I found myself by turns encouraging and reassuring them, Fred deciding about buying his first house or traveling, Francesca leaving her “good job” for taking an ethical stand, Jana waiting for other young Camino friends who never came, and Felix – I just hugged Felix as often as I could get away with it.

They reminded me that I had moved on, beyond my teens and 20’s and 30’s, and they looked to me for some sort of wisdom I was not at all sure I had. Santa Barbara was no saint. The only thing I had to give them was experience, the gritty real-world learning of having been in hard places making hard choices, and living to tell the tale.

They reminded me that I had moved on, beyond my teens and 20’s and 30’s, and they looked to me for some sort of wisdom I was not at all sure I had. Santa Barbara was no saint. The only thing I had to give them was experience, the gritty real-world learning of having been in hard places making hard choices, and living to tell the tale.

So I told stories. As each fit into the stream of conversation, I talked about being newly divorced with preschool-age children and how perseverance had generated its own luck in finding a job, work which eventually became a career. About the humiliations of poverty, receiving food stamps that store clerks shamed me for using, just to buy a 79¢ mix to make a birthday cake for my three-year-old. About “This Damn House,” as I had christened the money-pit

I finally bought, a flat-roofed, wood-floored beauty in her day, leaking water and cold air and home improvement projects into all my weekends, but big enough and sturdy enough for raising

a family.

As I told my stories, images of my children rose up before my eyes, and I could hear their tiny voices and high-pitched laughter, their arguments and tears, and see them expectantly giving me gifts of smudgy kindergarten hand print art, receiving school awards, graduating high school, graduating college, telling me about jobs and friends and love relationships and having their first babies, buying that first house.

I knew I had lived all those experiences, and yet, I didn’t feel older and wiser. And yet I was. How strange, to become an elder without realizing it. I wasn’t convinced I had earned that position.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Brought up Lutheran, I knew Martin Luther had fought corruption he saw in the medieval Catholic Church, including the sale of “indulgences,” essentially “Get Out Of Purgatory Free” cards sold by church authorities, sometimes obtained by significant acts of penance – such as walking a pilgrimage. Since starting the Camino, I had learned that this substitution had gotten to the point where some people in the Middle Ages hired pilgrimage-by-proxy, rich sinners sending poor serfs out to risk their lives on dangerous trails to holy sites, obtaining a compostela in the name of the wealthy scoundrel.

I had discovered a deep satisfaction in walking my own Camino, finding my own way, carrying my own burden. I was also discovering my own delights, and taking them, intentionally and without apology. Not very Lutheran. I knew I was being changed by the Camino, and would not be returning to my previous life, my 8-to-5 office, my weekends at plumbing supply stores. I was dancing over obstacles, surfing this powerful experience under a glorious sun. The rebel angel inside was singing, some sort of loud, punk rock anthem, the only words I could hear:

remember all the desperation of our love

the teary kiss, the frantic hug

the joy we crucified, a passion playand on that cross we built ourselves we hung our love

and like a phoenix from a dove

we burned the tree that held our heart’s desiresmoke and cloud

days of pyres

running on fireremember looking for the key for every door

and finding none, imagined more

the possibility of heresyremember when we realized the world was round

and more than this could well be found

and how we raised a sail to save the daysmoke and cloud

hazy tower

prison on fire— “The Reformation”

Indulgences required a “Pardoner.” I had finally figured out that this pardoner was me. And the sinner, too, was me. I was the whole shootin’ match. The way out of the fiery gunfight was to quit fighting – quit fighting my history and myself.

I had come on Camino to atone, to make peace with 17-year-old me, the lonely, brilliant, sensitive girl I’d tried to kill off over all those years, for her belief in us. In me. Here she was, defiantly singing the Reformation at the top of her lungs.

Leaving the tower behind was the road to reconciliation.

All I needed was the key. I needed to commit heresy.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, “indulgence came to mean the remission of a tax or debt. In Roman law and in … the Old Testament (Isaiah 61:1) it was used to express release from captivity or punishment.”

— New Advent

It was easy to know when I had reached the Old City of Lugo – I faced a massive Roman wall. Over twenty and sometimes thirty feet high, 14 feet thick occasionally bulking to over 20 feet across, it stretched a gargantuan two-kilometer ring around the central core of Lugo; over a mile of protective stone. UNESCO described this World Heritage Site: “The defences of Lugo are the most complete and best preserved example of Roman military architecture in the Western Roman Empire.” The wall was built in the 3rd and 4th centuries. It boggled my mind: I was standing in the far western reaches of the Roman Empire.

I entered by the Prisoner’s Gate. For hours, I toured the Roman ruins within the wall. Mosaic tiled baths under the street were covered in glass. The same for a section of aquaduct. Temples to Roman gods stood below ground level, next to Christian churches above.

One such temple was Casa do Mitreo, or, House of Mithras. Mithras was a god popular with Roman military men during the time the Walls of Lugo were built, a blended persona based loosely on an even older Mithra from Persia. This Zoroastrian divine angel of oaths, covenants and contracts was hailed as “Mithra of Wide Pastures, of the Thousand Ears, and of the Myriad Eyes.” To the Romans, Mithras’ “wide pastures” referred to his watchful eye over cattle, the currency of many contracts.

As I wandered the Old City, I remembered a gift of wisdom Emma’s father had given me about my sons, especially sweet, creative Daniel, my own Ferdinand the Bull who, as a child, had preferred sitting and smelling clovers on the soccer field to fighting for the ball. He had told me not to rein Daniel in, but to give him a wider pasture, room to roam. I, too, had needed this wider pasture, always. What Emma’s father could give me was the idea, the story, though not the freedom itself. That I had to take, like a stolen key.

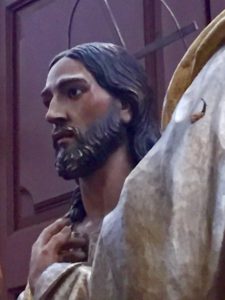

This was how I perceived Mithras. Often considered the pagan model for the stories of Jesus, he was the originating idea, the spark. Many scholars drew parallels between the Romans’ December 25th Feast Day of the Unconquerable Sun and the birthday of Mithras, as he was considered an embodiment of the ever-returning sun, and would have been celebrated on that date. His promise to protect was sealed with the blood of the bull, like children pricking their fingers to solemnly swear, becoming blood brothers, becoming Jesus’ story of giving his life-blood for all of humanity.

Yet Mithras was also depicted riding a bull. The bull didn’t die; it lived. It carried Mithras where he needed to go. Onward. Far afield.

This partnership formed the original contract. One of my dearest friends from those long-ago kindergarten days of our children, my beautiful hippy-artist pal, had wisely surmised, “You came to this life, not to be with any of these men – your contract was with the children.”

She was so right. We’d sealed that contract in blood. Paid in full.

He has sent me to heal the brokenhearted,

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and the opening of the prison to those who are bound….— Isaiah 61:1

I climbed a staircase of stone, and stood on the Roman Walls of Lugo, looking out over the city, back across time. As I looked over the edge, I remembered my own poem about the water man, back along the northern coast: the wall is open, peregrina. It was true. The gates of the massive walls here all stood open, like triumphal arches.

As I slowly walked the path along the top, I thought of what I’d hoped to give my children by this seemingly reckless, irresponsible choice to come to Spain and walk the Camino: that spark. The idea that if they tried to live a larger life in the world, they wouldn’t die. They would find a wider pasture waiting. They could take the steps, see over the top of their own confining ideas of themselves, break down their own limiting walls. Walls for protection can become prisons over time; this truth, I knew.

And then I heard something sweet, carried by the wind to me as I stood high on the wall, a child’s voice below: “Mom-my….” In it, I heard Meghan, and then Daniel, and Zach, Emma and Magnus.

They had needed me, and I had answered. Or maybe it was the other way around. We had become partners, giving each other hope, and after the Thousand Ears of a listening mother, a mommy’s Myriad Eyes watching over them, they had given me what I had not been able to give myself, what I had not allowed: forgiveness for my failings, and freedom.

Indulgence. They told me, “Go.” They told me, “This is your life – fly away and live it.” They told me, “Spend all the money. If you run out of money, we’ll send you more.” And best of all, offering me that glimmer of hope I was watching for, they told me, “You know what? I have to say, I’m a little jealous.”

Mithras the Bullrider, may I stoke the fires of that spirit until it burns like the sun, until they recklessly, irresponsibly, and self-indulgently refuse to live captive or unreconciled to themselves in any way, and though they find a wall on one side of the Great Tree, may they find a gate just waiting on the other, opening for the ride of their lives.