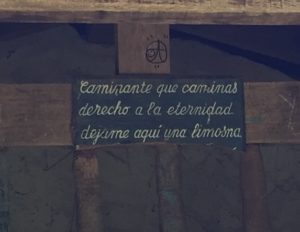

we shall be free

my backpack

is heavy yes

I agreed

but I alone must carry it

and if I emptied every item out

still it alone

is heavy

my backpack

is my life

At the Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias, I saw 19th-century landscape paintings of places I had just been. Paintings about the apple harvest, and cider-making, the people’s workaday wear like colorful peasant costumes. A tall painting of a young woman with two children captured my attention – her face was so exhausted. Children in many paintings, running down the beach, helping with the harvest, and one who drowned, the father’s face a portrait of anguish.

The museo had an El Greco, a Picasso, and a Dali, but I sought the Asturian painter José Uría instead: his “After the Strike” was so dark, and so human. The lighting he created told the story.

Like the cathedral in Santander, the museo had a section of glass floor. Underneath, the stones below the museum turned out to be a very early Roman fountain, stylized by Asturian design. It dated to the years 400-424 CE. I could look down and see the drain for the water, and marks where a huge heavy stone had been set to seal the fountainhead.

What wonders found beneath my feet, and all for free. Art for free. Painting, sculpture, Roman architecture, the opera and the theater that is Mass. All for free.

On into the countryside, I slept next in an old school at Venta del Escamplero, a cornfield across the road, amid hills, and farms with cows, and dogs barking, crows squawking endlessly. I had now seen apple, pear, lemon, orange, and eucalyptus trees; grape, black raspberry, and kiwi vines; oh, and plum and apricot trees, too, as of yesterday. Most mornings, I found a handful or two of raspberries for my breakfast. A tiny pear was delicious. This day, three little perfect plums blown down by the wind. A windfall. I only ate what fell into my path, or was branching out toward me into the path, never reaching through or over any fence. No stealing, just pilgrim bounty, which I superstitiously adhered to, lest I tempt Fate to cast its Evil Eye my way.

Enormous succulents grew along the roadside – I felt fairy-sized as I saw prickly pear cousins with pads the size of dinner plates, and mother-in-law’s tongue with sword-shaped leaves as big as me. Geraniums, roses, and hydrangeas were garden favorites, and, with the succulents and what I thought of as “house plants,” overflowed pots on every windowsill and doorstep and at every gate, plump, beautiful colors filling towns and villages. Everything bloomed; color and aromatherapy, no charge.

Today started as one of those easy days where you walk with someone and the kilometers fly by. I met Beata from Poland. Only a couple years older than me, she had two daughters whose ages were similar to my daughters’, and she taught sign language. We talked about communication, the hidden culture of the deaf; we talked about our daughters; we talked about ourselves.

At one point, Beata had commented on how big my pack was, that it looked heavy. I agreed, telling her I often gave things away to lighten my load, but the pack itself was older and heavier than the new ones, so it was never going to be light. Beata suggested I use the postal service’s pack transport service: for a fee, your backpack is hauled in a van by postal workers to the next albergue you designate.

“No, no,” I responded. “No one can carry my pack for me. Only me. I have to carry it.”

“Many Americans like it, so I thought you might like it,” she answered.

“Many Americans use the pack service?”

“Yes.”

I sighed, embarrassed by Americans abroad once again. “I will carry my pack. But thank you.”

Beata’s grandfather was a World War II hero, a Polish political resistance organizer who was arrested and sent to the concentrations camps. There he was shot, so he could not use the power of his words to organize the prisoners. Since then, it had been very hard for the men in her family to quite measure up to his superstardom; I taught Beata the phrase, “a hard act to follow,” and she agreed.

The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.

— Albert Camus

I thought of the power of our words to shape images, unite or divide people, liberate possibility or chain to stone the ideas of who we were, or what we could become. I had been talking a lot about socialism with many of the Europeans along the Camino, and had come to believe that a mature America would take a democratic-socialist stance – the fact that such a wealthy nation allowed any of its citizens to be hungry, homeless, or sick without medical care was truly obscene.

But American salesmanship of image was one of our greatest talents, and the Europeans I had met were very surprised to learn that, until I sold my house, I was poor, that my career was helping homeless Americans, and that many of us could not afford housing. However, they quickly understood that corporations run the country, as they connected the ownership of newspapers and TV, of pharmaceutical companies, of insurance, of health care, of real estate, banks – almost all corporate. And these powerful corporations paid for the campaigns of politicians, and got them elected. So America was actually a capitalist republic, not a democracy, owned and operated by a select few, and we talked about how close this looked to fascism.

Fascism is a systematic control. A dictator wields power from an autocratic position on high, immune, untouchable, forcing behavior and crushing opposition. Resistance is futile. Yet the very system foments rebellion. I was living proof.

For Beata, it was also personal. Fascism had murdered her grandfather and so much more. It had stolen the future. The men in the family were a continual disappointment to the women in the family, who could never protest enough. The Resistance would never die. By turns scornful then fearful, the women wanted nothing to do with the men they had chosen to stand at their sides, between them and a world they found all-too-frightening, a world of harsh consequences. So they complained.

It is difficult to free fools from the chains they revere.

— Voltaire

Braying like the donkeys we passed in fenced pastures along the way, Beata had learned to nitpick and bitch, gripe and swipe at the small details of life that she stacked up as proof of abuse, treachery, and danger lurking everywhere. They didn’t have green salad on the pilgrim’s menu. No fish. The flan was pre-made. The beds were creaky, mattresses thin. It was drizzling outside; our laundry would never dry.

When she wasn’t making negative comments about the food, the bar owner, the hospitalero, or the albergue, she was startling – violently – at every encounter along the way. Every encounter. Every dog bark made her physically shake. Every car that passed caused her to literally jump off the roadside into a ditch or driveway. Every person walking behind us disturbed her enough that she continually turned around to keep an eye on them.

Her energy was draining. At first, I tried to reassure her – “that dog’s on a chain” or “oh, I met them, they’re nice” – but it made no difference, so I quit. She had mentioned that she didn’t navigate well, and on previous trips she had found “guides” for her caminos who led her from one albergue to the next for weeks. I realized I was being groomed, giving her directions, finding the arrows, tending her never-ending fear.

Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains.

— Jean-Jacques Rousseau

I suspected she had a lot more trauma in her past than her grandfather’s story. Much like my mother, I recognized with a jolt. My heart went out to Beata. My mother’s energy was a big part of why I was hiking the Primitivo. To let it go – literally.

I carried a hideous rock under one water bottle, a beauty under the other. Balance of a sort. While the beauty was red, gracefully shaped and textured, found along the Camino, a part of the Camino, the hideous rock was from my mother’s town. From a parking lot. At a strip mall. The town where I had graduated high school. Beige, with pinkish lumps all over it like acne, I really disliked the look and feel of that rock. Which was why I picked it up.

I had wanted to bring a burden stone with me, to let go of at the end of my Camino. I had thought to throw it into the Atlantic; but lately, I had realized I would be letting it go along the Primitivo. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, ancient to ancient. The old energy of fascist trauma would end by taking the high road. I would leave my mother’s misery on the mountaintop.

Now I’ve been free, I know what a dreadful condition slavery is.

— Harriet Tubman

But first, I had to leave my mother’s misery immediately. We had stopped at a bar to use the toilet and get a coffee. I drank mine quickly while Beata used the restroom. When she returned, I talked to her about preparation for the next stage of my journey, and told her I would be walking on – alone.

Among the peregrinos, it was understood that anyone, at any time, could decide they wanted alone time. People had walked away from me repeatedly, for weeks. We would smile and wave, and sometimes saw each other again, sometimes not. I now invoked this privilege, with minimal preamble.

For Beata, in the moment I smiled and wished her a “Buen Camino,” it was a horrible betrayal.

A grown adult, she was immediately abandoned and fearful, on the Camino she had set out alone to walk…no hiking partner, no travel companion, no buddy. She wasn’t looking for a friend just yet; first and foremost, she wanted a free guide.

And no one, I wanted to tell her, can guide you on your own Camino. But it would have made no difference. So I walked away.

Nothing personal. Except, of course, it was.